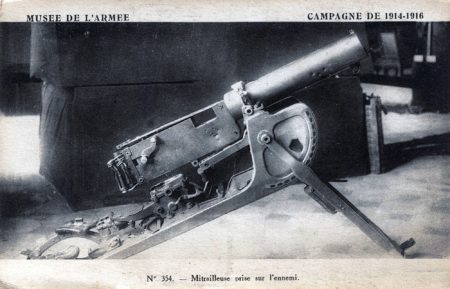

A souvenir from SMS Goeben or SMS Breslau

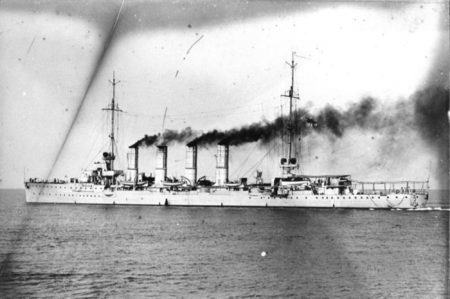

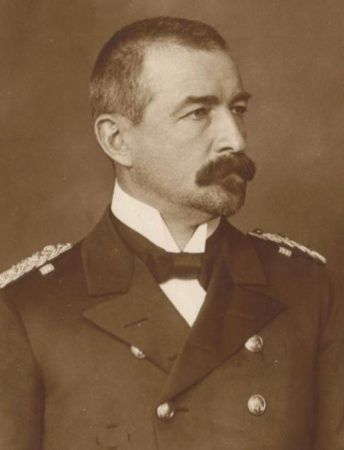

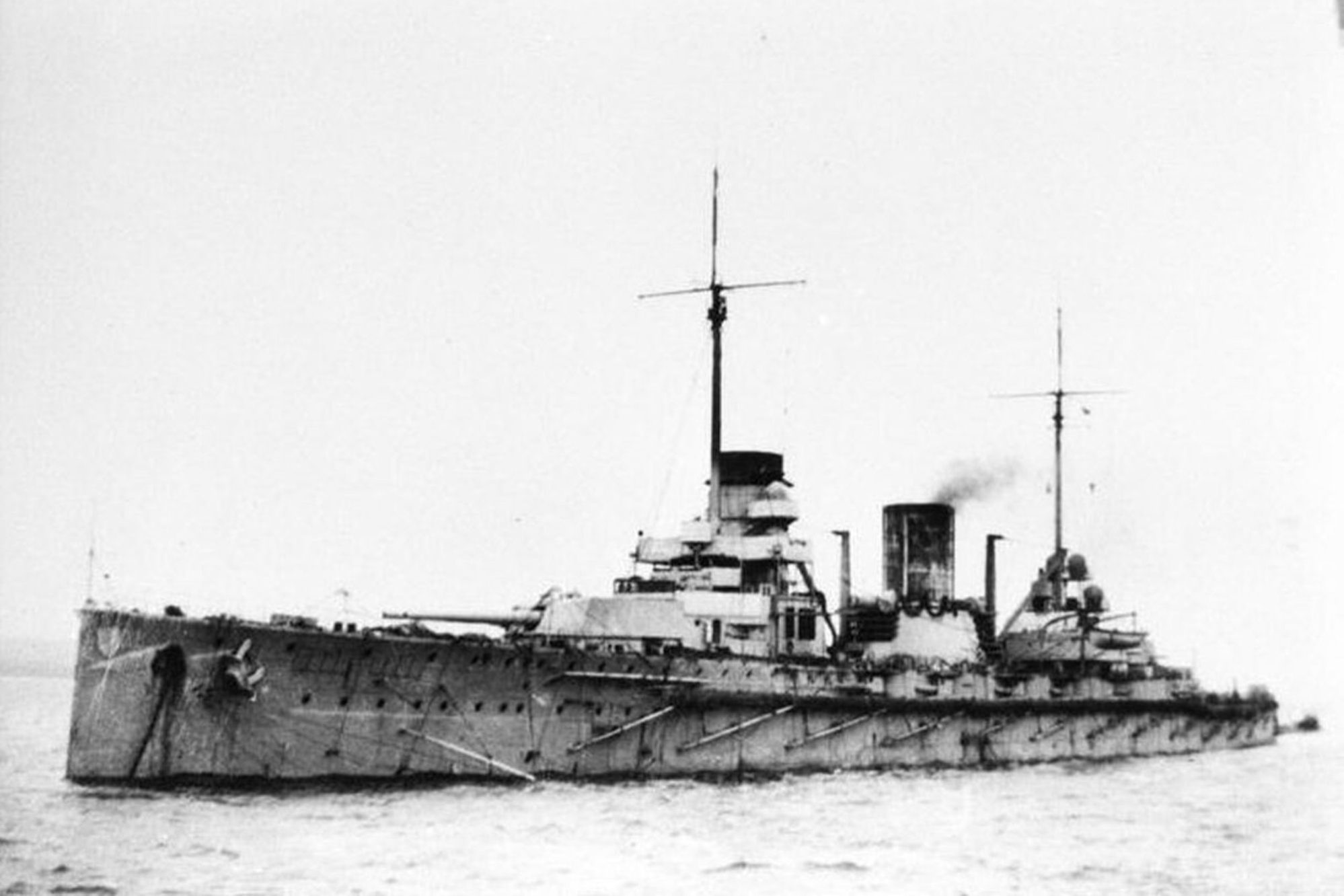

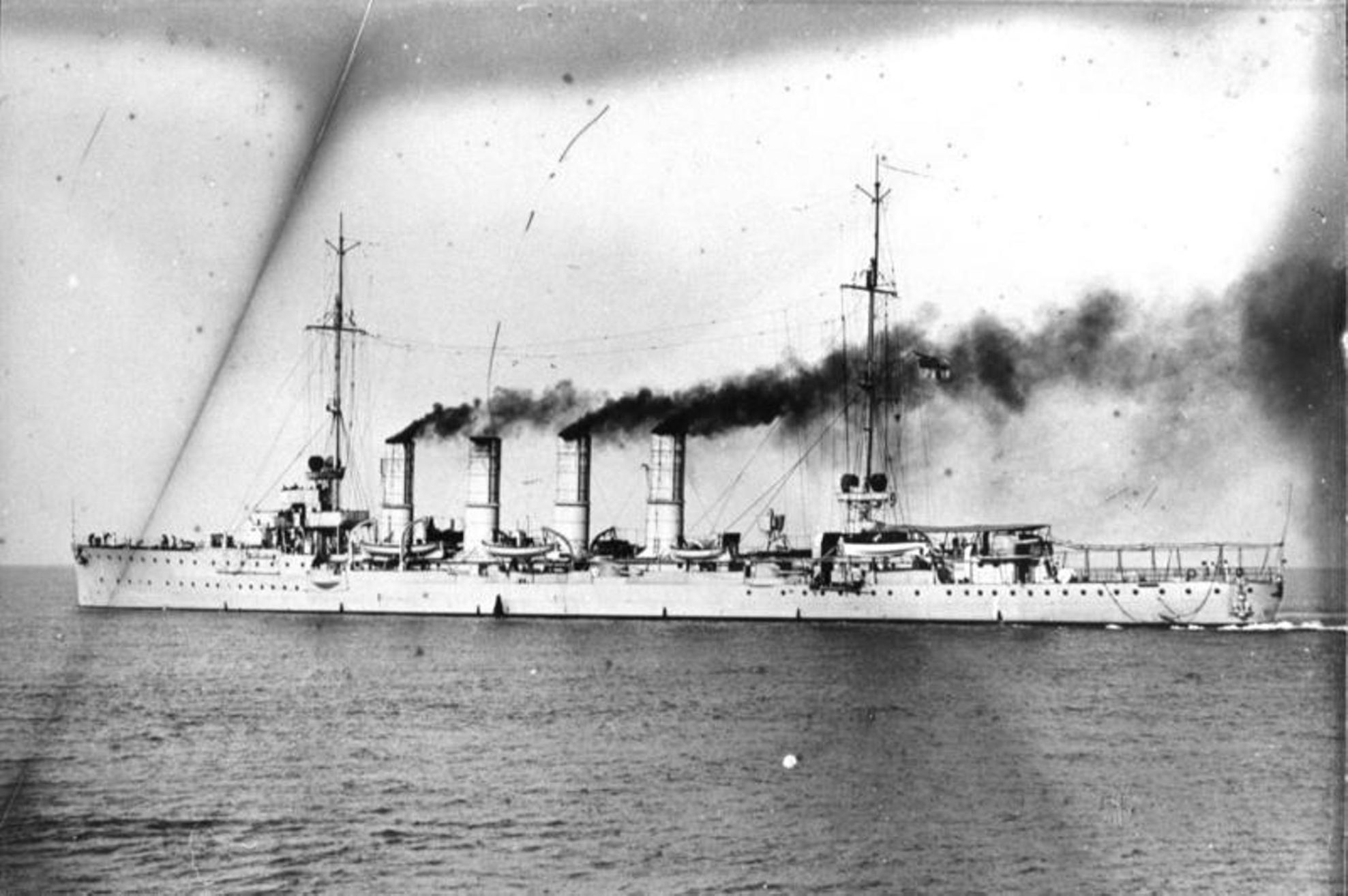

During the Balkan War of 1912 between Turkey and Bulgaria, an international maritime force was created to protect the interests of the Western powers in the Dardanelles strait. The Kaiser sent two ships of the Imperial Navy under the command of Admiral Wilhelm Souchon, the light cruiser SMS Breslau and the newly created battlecruiser SMS Goeben, which was not yet fully completed. The two ships, constituting the “Mediterranean Division” (Mittelmeerdivision), left Germany on November 5th and 6th, 1912.

The bombing of Bône and Philippeville

Their fate sealed by the declaration of war of August 2nd, 1914, and without precise instructions (the communication means of the time being very different from those of today!), the two ships decided to disrupt the passage of French troops from Algeria to Europe by bombing the port facilities and warehouses of Bône and Philippeville (Algeria was a French colony at the time). The following order was given on the morning of August 3rd:

- Take all measures to sink the ships so that they do not fall into the hands of the enemy under any circumstances.

- For information on the enemy, see the news received yesterday by radiotelegraphy.

- Mission: To wear the enemy out, attack him according to the possibilities on the coast of Algeria and on the Bizerte-Toulon line of communication, to prevent him from transporting his troops to France without taking major precautionary measures.

- Execution: Tomorrow, at dawn (04:30), the Goeben will be in front of Philippeville, the Breslau in front of Bône. They will first recon while under the Russian flag, what lies in each of its ports. They will then try, after hoisting the German flag to destroy enemy warships, troop transports, and installations that can be used for these transports. Save ammunition, do not engage against land buildings. Sail west until you get out of sight of the coast and then sail towards Spartivento (Sardinia).

Signed: Souchon.

On August 4th, at 06:00, the Goeben commanded by Captain at See (Kapitän zur See) Ackermann positioned in front of Philippeville late on schedule because of the traffic leaving the port. At 06:08, he bombed the port facilities for 10 minutes with high explosive 15 cm shells then moved away to the west before heading north-east as soon as the coast was lost from sight.

Breslau, commanded by Frigate Captain (Fregattenkapitän) Kettner, opened fire on several steamers at the dock, then bombed a semaphore. Fires and explosions were observed at Bône, and the native troops suffered losses at Philippeville. The radiotelegraph stations on land quickly announced the news. Therefore, the French vice-admiral Boué de Lapeyrère directed his entire squadron due west to protect Oran and Algiers, which allowed the two ships to escape while having disorganized the transports of the XIXth French army corps.

The escape

A message received on August 4th, at 02:35 read:

“August 3rd, alliance concluded with Turkey, order Goeben and Breslau to reach Constantinople immediately. Headquarter. ».

This was the wisest decision to take in the circumstances of the time, since the disproportion of forces was overwhelming and going through Gibraltar’s strait illusory to join Germany. Indeed, the Allies could deploy 15 battleships, 3 battlecruisers, many cruisers, battleships and light cruisers, 8 flotillas of destroyers, submarines and special ships. The meagre German squadron could only rely on its enormous speed for the time, since at full steam the Goeben could hope to flee at 24 knots (44 km/h), but with excessive coal consumption. The two ships reached Messina (Sicily, Italy) followed by the British fleet, and there were able to embark the necessary fuel by taking the coal stock of the German commercial steamers, the General, the Mudros, the Kettenturm, the Ambria and the Barcelona providentially at anchor in the port. The crews were supplemented by embarking German civilian sailors who could be mobilized as well as reservists and volunteers for the duration of the war.

The two fugitives managed to deceive the British surveillance, and during the night were still able to escape. A brief engagement ensued between the light cruiser HMS Gloucester and SMS Breslau. According to the sources, either the Breslau took a shot without gravity (version found on various internet sources during our research in December 2022), or this one inflicted 4 shots to Gloucester at 13,000 m (version reported in the French book “The Goeben and the Breslau“, published in 1930 by Payot, Paris). If shooting at such a distance, on a platform subject to roll and pitch, seems exceptional today, engagements at such distances were in fact not uncommon at that time. In any event, the Gloucester abandoned the pursuit.

A civilian refueling steamer, the Bogadir was able to fill the ships’ holds with fuel on the night of August 9th to 10th, along the neutral coast of Greece. Then after embarking a Turkish pilot to cross the minefield preemptively barring the Bosphorus access strait, the Goeben and the Breslau anchored on August 10th, at 17:17 in front of the friendly port of Çanakkale (Turkey).

Under Turkish flag

Faced with the impossibility of leaving the strait without being irreparably destroyed by British units in ambush beyond the mine-barrage, the two German ships were gifted on August 16th, to the government of the “Sublime Porte” in compensation for two battleships ordered in England almost completed and that the navy of his “most gracious majesty” had requisitioned. The crews sometimes exchanged the sailor cap with the imperial arms for the Turkish fez and the crescent moon flag was hoisted at the main mast. An original shared command was instituted: under Turkish command for the maneuver and German for combat. On September 23rd, 1914, Admiral Wilhelm Souchon was appointed commander of the Ottoman war fleet. Thus, SMS Goeben became Yavuz Sultan Selim (often shorten as “Yavuz”) and SMS Breslau became Midilli.

However, to bring Turkey into the camp of the Central Powers, a pretext was needed. Sultan Mehmed V, an elderly figure without any real presence, was pushed into it by his War Minister, Enver Pasha, leader of the “Young Turk” party and a convinced Germanophile. He organized a provocative raid – the Black Sea Raid – against the long-time enemy by launching the Goeben and Breslau at the head of a small Turkish squadron with incredible audacity. During this raid, which took place on October 29th, 1914, Goeben successfully attacked the Russian fortress of Sevastopol despite fire from Russian coastal batteries. Breslau, meanwhile, bombed Novorossiysk: war was declared by the Turks. They continued their marauding in the Black Sea for two months, creating a psychosis and disrupting all Russian traffic until December 26th, 1914, when the Goeben hit two Russian mines at the entrance to the Bosphorus, which damaged it and immobilized it for many months.

To arm the forts of the Dardanelles strait, the Goeben ceded the:

- On March 2nd, 1915, two 8.8 cm guns and their ammunition.

- On March 9th, 1915, two hundreds 15 cm shells.

- On March 16th, 1915, 12 mines.

- On March 20th, 1915, the last 20 mines he had left.

It would also let go of another two 15 cm cannons to reinforce the defenses of Constantinople.

The fate of the machine guns

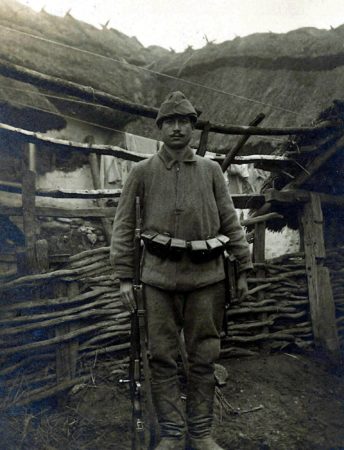

The 5th Turkish Army had realized that it was almost completely lacking machine guns. German General Otto Liman von Sanders asked the commander of the fleet to lend him his support. This request was met. Officers and men from the Goeben and Breslau were chosen and on May 2nd, the Artillery Officer (Artillerieoffizier) Wilhelm Boltz of Breslau left for the Dardanelles with 44 men and 8 machine guns. This troop, together with the personnel already ashore to observe the indirect fire of the battleships, formed the shore detachment of the fleet under the command of Lieutenant-Commander Rhode. It took an extremely important part in the defense, and it was thanks to its activity that various positions were held and the enemy’s attacks repelled. Although the officers and men had not received special instruction in the use of machine guns ashore, they were able to adapt as the resourceful and active sailors they were. When the party arrived at the Dardanelles on the afternoon of May 3rd, they were ordered to go to Krithia, to assist the southern group fighting at Sedd-Ul-Bahr against the British and French.

After a forced march they arrived at the headquarters around midnight. When they arrived, Boltz was ordered to advance immediately towards Krithia with his machine guns, as the decisive battle was to take place during the same night. He could not advance to the point because of the extremely violent fire from the opponent. The difficulties in which the sailors would have to fight were revealed when the detachment, divided into two groups of four machine guns each, had to move to other positions. Having no knowledge of the country where there was no road, no Turkish guide and no suitable interpreter, the two factions acted independently of each other and clashed with native troops who assaulted the small group supposedly enemy and disarmed them. It was thanks to the arrival, quite by chance, of a German officer in the service of Turkey, that the small troop was able to escape its unpleasant situation, but not without having lost two machine guns that the natives had taken. When the detachment arrived on the battlefield, the Turkish troops, under the extremely violent effect of the fire from the ships, were in full retreat. The machine guns were immediately placed in battery. Their intervention first stopped the English troops and then allowed them to counterattack by completely throwing off the attackers. During this first night intervention, the small force suffered heavy losses: the fighting claimed three dead, and seven wounded; a machine gun was put out of service by shrapnel.

On May 7th, at 11:00, a particularly violent fire of shells of all calibers and shrapnel from the ships served as preparation for an assault. W. Boltz describes the assault as follows:

“In thick columns, always in platoons of 50 to 60 men, they advanced bravely, offering a perfect target for Turkish artillery and our machine guns. Whole ranks fell, but always new columns went back to the assault. When our machine guns had exhausted their ammunition, the men took the rifles of killed Turks and continued to fire. The attack was not pushed back until about 5 p.m., the enemy had to suffer huge losses there. The trousers and red kepis of the French offered excellent targets. »

It is remarkable to note that if the German officer’s tale is accurate, the French troops were still equipped with the very visible, remarkable and deplorable red trousers in May 1915!

The commander of the 3rd Turkish Division also placed all Turkish machine guns under the authority of W. Boltz. He was to take position, on the evening of May 7th, on the Kereves Dere, with 11 of these weapons.

On May 8th, the French fleet subjected the Turkish positions to a very violent bombardment which lasted from 09:00 to 16:00. The enemy attack then took place, and the first time it managed to be stopped outright. Due to a foot injury, Boltz had to hand over the command to Master Artificer Schubert. He was wounded twice to the head; command then passed to the second boatswain Seckendorf. The situation became critical. Boltz decided to resume command despite his injury. He arrived about 17:00, just as a second and very violent attack by the English was coming, to which the left wing of the Turks, where the machine guns were, resisted well. As they went to the counterattack and the bayonets were already put onto the barrel of the rifles, the right wing gave way and retreated backwards dragging the left wing with it. The German troops considered that their main task was to stand their ground and cover the Turkish retreat.

As a result, the Germans remained firm in their positions by continuing to fire. When Boltz was finally forced to withdraw, it was no longer possible for him to take all his machine guns, because many Germans had already fallen, and the Turks of the detachment had already withdrawn. Three machine guns were abandoned after their bolts had been removed (an important point for the rest of our story!). During the night, the Turks drove back the English; so, a patrol was able the next day to try to save the abandoned weapons. The position was completely upside-down; one machine gun was found completely demolished; it is likely that the other two were under the rubble. Of all the detachment that had landed on May 2nd, only 7 men remained in fighting condition, all the others had been put out of action by wounds or diseases.

Seen from the French side, the composition of the German troop is described as follows in the weekly review the “Panorama de la Guerre” (Panorama of War):

“Among the captured enemy soldiers were six Germans who were part of a machine gun company. This company, which lost in action two-thirds of its pieces, one of its officers and almost all its men, consisted exclusively of Germans. Some were sailors landed from the Goeben and Breslau, others Prussian subjects living in Turkey and mobilized on the spot; others had come from their countries through Austria and Bulgaria. »

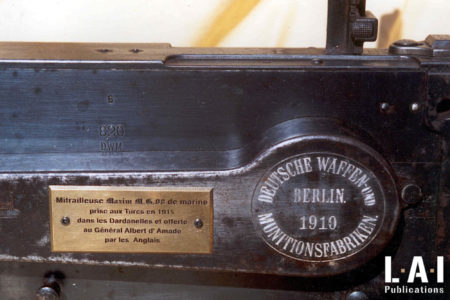

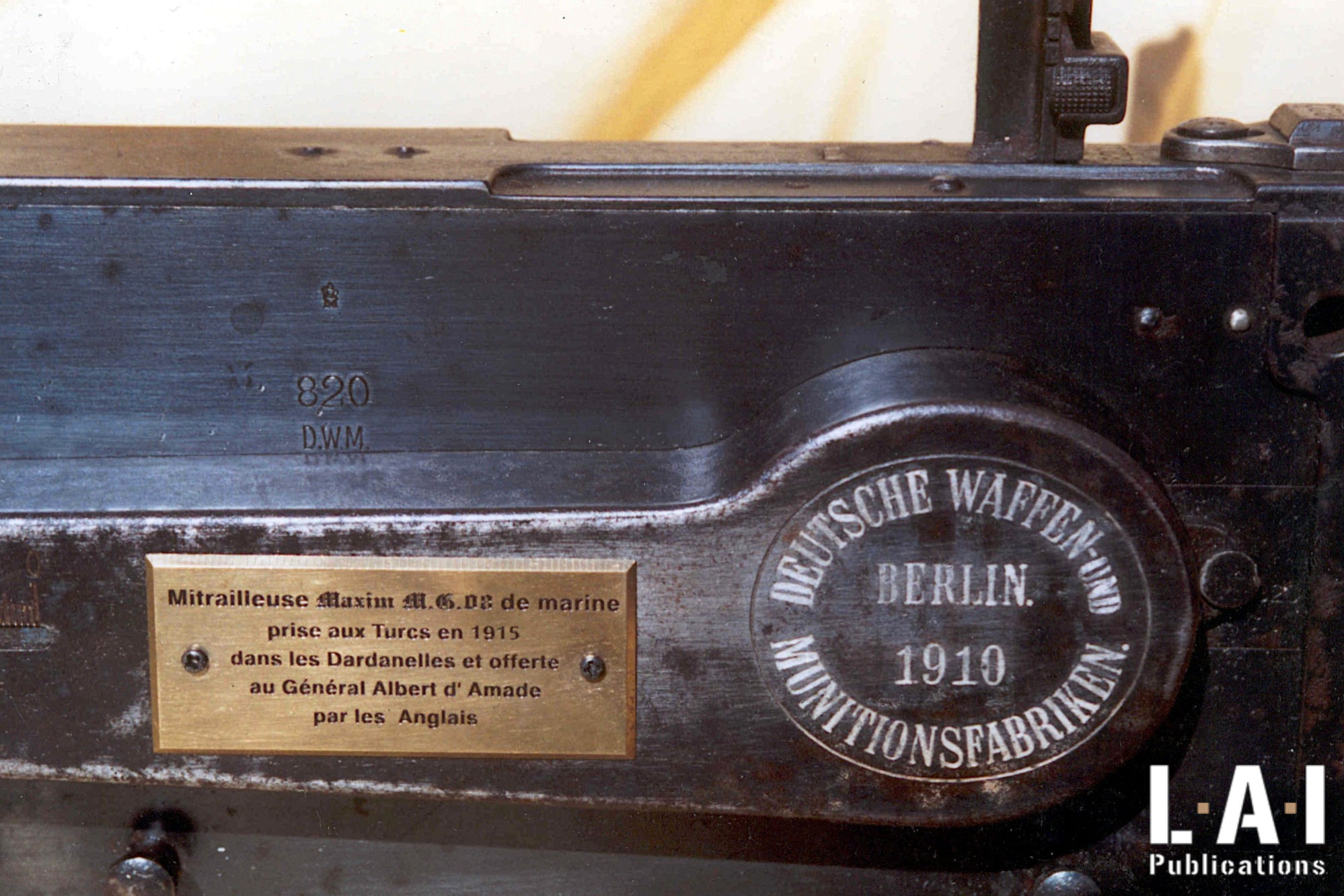

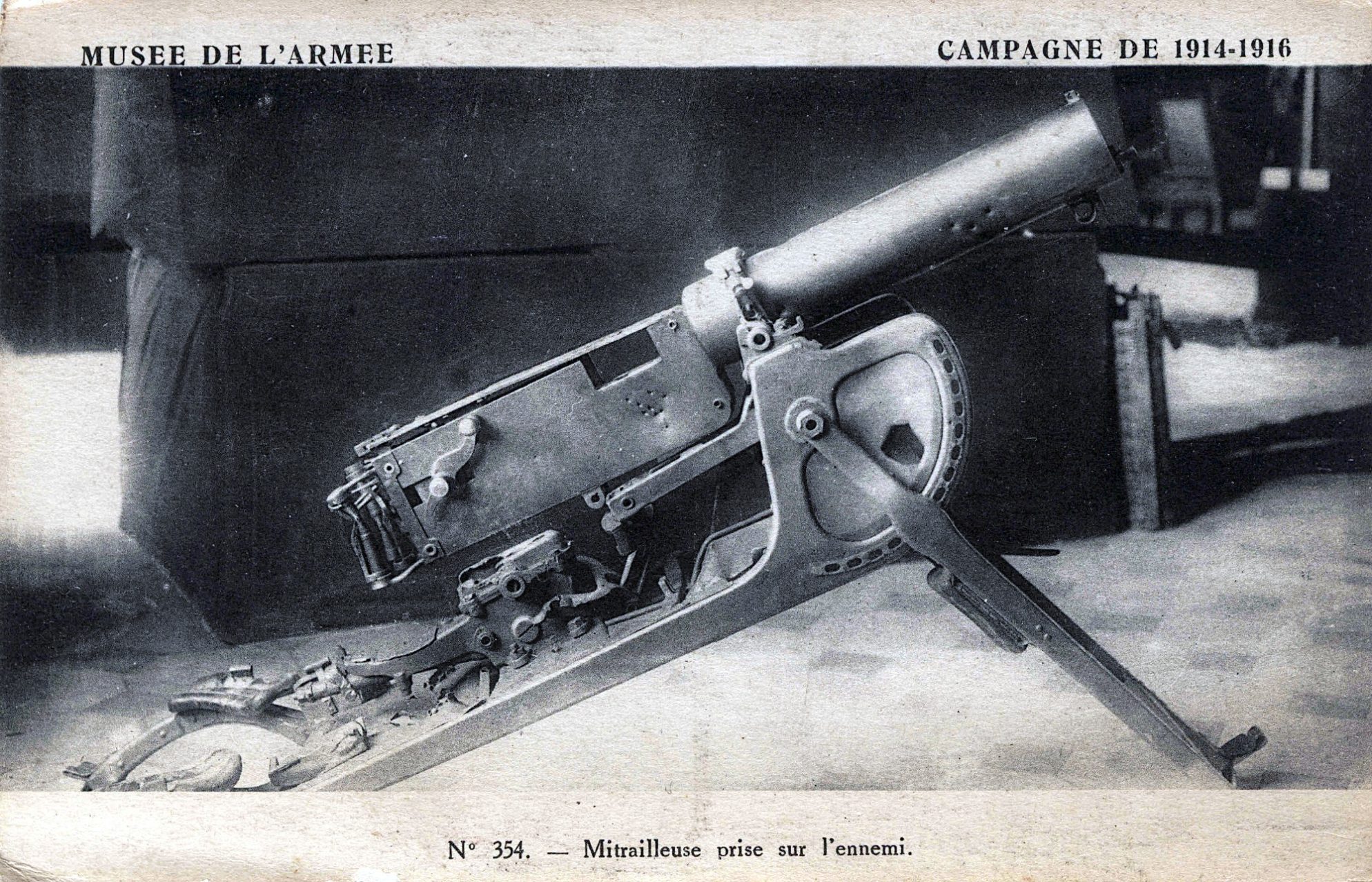

One MG 08 machine gun

The French General Albert d’Amade, sick and especially demoralized by the death of his son Gérard d’Amade on January 26th, 1915, at the age of 19 on the Verdun front (not the battle of the same name, which took place later in the same area) and the stalemate of the offensive, was replaced at the head of the French detachment in the Dardanelles by General Gouraud on May 15th, 1915. During the farewell ceremony, the British General Staff presented him with a “Turkish” machine gun taken the day before by their troops.

The general brought his souvenir back to France: it was still in the attic of his castle of Saint-Étienne de Tulmont in Tarn-et-Garonne in the mid-90s. At that time, it was possible for me to recover, with the help of the gendarmerie legion of Midi-Pyrénées, this prestigious but now cumbersome vestige for heirs anxious to respect the law about owing machine guns in France. After a devastating but necessary passage to the proof-house of Saint-Étienne, where the weapon was brought into conformity with the law by being deactivated, and where it “lost” its bolt (stolen by an indelicate or lost during transport?), the venerable machine gun could finally aspire to a peaceful retirement by being enthroned in a showcase.

The weapon, number 820, was manufactured by the prestigious Deutche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken (D.W.M.) in Berlin in 1910 as evidenced by the superb marking on the protective cover of the rate control spring. It was received by the Imperial German Navy and rightfully hallmarked in various places with a splendid “M” crowned with the specific crown of the navy. This small hallmark classifies it, given its history, as one of the machine guns landed from one of the two German ships present in the strait at that time and is thus rewarded with the rank of historical relic! The receiver cover is engraved “8 MM MACH. GEW.1908” which helps if necessary to classify the weapon as a German service weapon, the Turkish army mainly using a 7.65×54 Mauser caliber.

The machine gun used by the German Navy is indeed different from the models of the Army. Adopted in 1908 to replace the commercial model with bronze frame, the Maxim 1908 naval machine gun was also used by German colonial troops defending the Reich’s possessions in Africa, Papua New Guinea or the port of Tsingtao in the Shantung Peninsula in China… A port well known to Chinese beer lovers! The main difference quickly visible with the army model is the absence of the two-sled mount fixing studs that protrude from the front of the frame on the barrel cooling housing. Indeed, the Navy specific mount (absent on the General’s weapon) is fixed in two holes leading from side to side at the front end and below the frame and is secured by two keys with rapid disassembly; this device certainly making it possible to put the weapon in battery with a simple mounting cradle on the railing of ships to repel boardings.

It was written that during the Second Battle of Krithia, General d’Amade commanded a combined force, composed of the 1st French Division (a Colonial Division and a Metropolitan Brigade has six battalions each) and the British 2nd Naval Brigade formed by the Hood, Howe and Anson battalions of the Royal Division. The battle began on May 6th, 1915. That same day, the Hood Battalion captured a Turkish machine gun while storming an enemy position known as the “White House”. This war catch was offered by the Hood Battalion to the general when he visited them in the back lines in a rest camp on May 14th, 1915, four days after the end of the battle.

Curiously, the bolt and feed box mounted on this weapon conform to the model but bear the number 817A (bolt) and 817 (feed box) and the Navy hallmark. This seems to indicate:

- Either a reassembly of circumstance from another weapon previously recovered, the object having been completed for the purpose of being a gift of prestige by the English. This hypothesis seems unlikely to us, the report cited above mentioning the capture of a single machine gun.

- Or an occasional repair carried out by the German sailors by “cannibalizing” another of their ship’s weapon.

It is very interesting to note that the numbers of the weapon on the one hand and the bolt and the feed box on the other hand are very close: it is likely that the D.W.M. delivered batches of weapons specially manufactured to fulfill the order made for each ship, whose serial numbers were to follow each other. But it cannot be one of the three breechs removed from the weapons abandoned on May 8th, by Boltz, this MG 08 being captured on the May 6th! It is noted that during manufacture, the MG 08 machine guns had several bolts in their collective units, which explains the addition of an affix (A, B …) to the serial number present on this part.

There are few known period photographs showing this type of equipment on a ship. However, the landing company of the prestigious light cruiser SMS Emden was armed with the ship’s four machine guns when it landed in the Cocos (Keeling) Islands on the west coast of Australia to destroy the radio station and the submarine cable. Surprised by the Australian cruiser HAMS Sydney, the German ship succumbed after an epic fight. Three officers, six officers and forty-one men who were on the island were able with a small sailboat found on the spot, the Ayesha, to reach in a few months (November 9th, 1914, to May 6th, 1915) the coast of Yemen and join the Turkish-German troops in Palestine! They were commanded by Lieutenant Hellmuth von Mücke. He described their epic journey and spoke of the great help that the firepower of their armament gave them, both at sea and in confronting the hostile Bedouins while they traveled through the desert. The photograph he took on the Keelings clearly shows the tripod blind and its attachment under the weapon.

To conclude

The terrible devastation caused by the “grim reapers” traumatized an entire generation of sacrificed and left a lasting mark on the collective unconscious. In the thirties, some sulphurous authors did not even hesitate to evoke them in strange poems “O machine guns so often caressed in dreams … ». Alas, in Europe, the sinister barking of these machines resounded again in the East as an ominous toll!

The undefeated SMS Goeben surrendered to the Allies in 1918, then returned to service in the Turkish Navy under its Turkish name. It was withdrawn from service in 1961 and scrapped in 1973.

SMS Breslau was blown up by mines and sank on January 20th, 1918, off the island of Imbros under the command of Captain von Hippel. 162 men were picked up by English ships.

Gilles Sigro-Peyrousère

Bibliography:

- « Le « Goeben » et le « Breslau ». L’échappée du Goeben et du Breslau, les opérations navales des Dardanelles, le combat d’Imbros. », Payot, Paris 1930.

- « La Première Guerre mondiale », Susan Everett, Solar.

- « Le panorama de la guerre de 1914-15 », Jules Tallandier, Paris 1915

- “The Devil’s Paintbrush: Sir Hiram Maxim’s gun”, Dolf L. Goldsmith, Collector Grade Publications Incorporated.

- « L’équipage de l’Ayesha, aventure des rescapés de l’Emden », Lieutenant Hellmuth von Mücke, Payot, Paris 1929.

- Personnal Collection of documents and objects. Thanks to Christophe Dutrone for his help.

- Picture 08, copyright Imperial War Museum. Référence : Q 61092.

- Pictures 01 et 02, copyright Bundesarchiv (via the German Wikipedia).

- Picture 16: https://www.pressreader.com/uk/iron-cross/20201223/282797834094098