What could possibly have happened in the minds of the Soviets in the aftermath of WWII to develop and adopt a machine pistol? While it is obvious that this period was incredibly fertile in terms of gunsmith design, one really wonders how the adoption of such a weapon could have been thought of for a moment as “a good idea”. Perhaps this mystery lies in the arrival of a new type of weapon, the “assault rifle”, which had reshuffled the cards of infantry combat and somewhat downgraded the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More. Therefore, the question was what about the other weapons? In any case, from this conceptual struggle would be born an atypical weapon: the APS of I.Y. Stechkin.

A questionable tactical contribution

The machine pistol “Автоматический Пистолет Стечкина” or АПС (“Avtomaticheskiy Pistolet Stechkina” or APS, or “Automatic Pistol Stechkina”) was designed alongside the Makarov pistol in the aftermath of WWII. As for the Makarov, it was in Tula, one of the great places of Russian armament, that Igor Yakovlevich Stechkin was entrusted with the task of designing this selective fire weapon, originally intended for officers, non-commissioned officers and some specialized units. For once, it seems that the thing happened without competition, a fact quite atypical among the Soviets in terms of small-caliber weaponry. This development took place in the late 1940s (many tests having been carried out between 1948 and 1949), and in 1951, the APS was adopted alongside the Makarov. One can also wonder about the links that exist between the two weapons designed at the same time and in the same place: the mechanical similarities are disturbing. We invite the reader to take a look beforehand on the article about the Makarov (link here), wherein many elements mentioned here are detailed, including the development of the 9×18 Makarov ammunition. If the APS is of a remarkable mechanical design (and we will come back to this), it would however know a more limited diffusion than initially expected. Production would be stopped very quickly in the second half of the 50s (1958 according to some sources). The weapon was probably too expensive to produce, and its tactical contribution is a little questionable.

Because the whole question is here: a machine pistol, what for? Here, the thing seems simple, it is a question of putting in the hands of the public mentioned above, a weapon more tactically apt than a simple pistol, but without the bulkiness of a submachine gunSubMachine Gun More. It should be remembered that the comparison was then made with the excellent, but still cumbersome PPS-43. When we talk about comparison, we are talking about the work that would be done during the design of the weapon and firing tests. The thing seems logical: to make a weapon with the tactical capacity of a submachine gunSubMachine Gun More, but whose size is that of a semi-automatic pistol … it is a “Personal Defense Weapon” (PDW) that is not openly called as such! The thing is natural, the concept of PDW would not be formalized until many years later. There were certainly historical beginnings: LP 08 and Mauser C96 (including the variant firing burst M712 “Schnellfeuer”) no doubt about that, but also according to some points of view, the USM1 Carbine… Each time, these weapons have “missed the boat” of sustainable use as such. And for good reason, these weapons, which often have the “butt between two chairs” (TN: French expression) are caught up by reality: their contribution in tactical terms compared to a conventional handgun is, certainly, significant (increase of both range and hit probabilities) but is often done at the price of an unacceptable counterpart for a daily wear. What counterpart? Simply the weight and size are still much higher than a regular handgun. Why is this unacceptable for the public concerned? Well, simply because infantry combat is not their main mission… and that if the situation turns into infantry combat, then it will be better to fall back on more “classic” equipment: at the time of the commissioning of the weapon, it is the brand-new Kalashnikov rifle!

In his book “Soviet Small Arms and Ammunition“, D.N. Bolotin reports that the weapon, from the memory of I.Y. Stechkin, was extensively tested in the firing range. But the problem is there: the sole and entire vocation of this type of weapon is not shooting! Daily wearing outside of combat “situation” is a major component of its employment. And there, the Stechkin is not to its advantage: compared to a pistol (especially to a Makarov – Pic.07), it is heavy and bulky. And on a battlefield, you must feel lonely with a Stechkin in 9×18 M when everyone around is equipped with Kalashnikov in 7.62×39! And that has been well understood by “modern” PDWs from H&K and FN as they adopted a caliber (one more logistically … “nice”) more apt with distance.

Does the weapon find a better place in a police-type mission? Well, not really:

- Out of intervention, it is too cumbersome, and the burst is useless for the daily police mission.

- In intervention, why settle for a weapon with “bastard” ergonomics (we do not really know what to do with our off hand …) and not opt for a more stable (a SMGSubMachine Gun More) or even more powerful platform (an assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More, perhaps a compact one)?

It is easy to understand why the Soviets, no doubt quickly confronted with the reality of their costly mistake, so quickly put an end to the manufacture of this weapon.

So, obviously, the Mauser C96 and its notable use in the very young USSR had a decisive influence in the choice to develop the APS. But then the thing becomes even more disturbing: knowing the pros and the cons (of hitch hiking?) offered by this technical solution, why persist? Well, because faced with the unfolding of history, it may be necessary to learn from one’s mistakes. And this lesson was undoubtedly the greatest contribution that the APS ever made to the USSR.

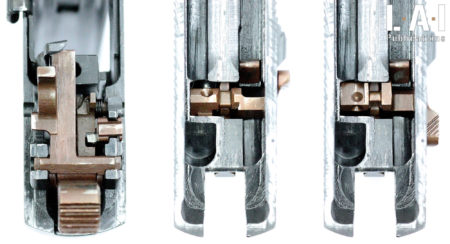

In Tula, a certain coherency at the turn of the 1940s

The ergonomics of the weapon are very close to the Makarov, which obviously seems not to be the result of chance. We are therefore facing a pistol with a single and double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More firing mechanism on which we find the magazine hook at the bottom of the grip, a slide stop and a selector on the left side (Pics.08 and 09). The selector stands instead of the Makarov’s safety/decocking lever. This selector offers 3 positions (from front to back):

- Safety / decocking: “ПР”, for Предохранитель

- Single: “ОД”, for Одиночная

- Automatic: “АВТ”, for Автоматическая

The safety of the weapon locks the slide and the hammer as on the Makarov, but also the firing pin, which is not the case on the Makarov. It must be said that the firing pin of the Stechkin is much heavier than the Makarov’s: its inertia is therefore much greater.

Annual subscription.

€45.00 per Year.

45 € (37.5 € excluding tax) Or 3,75€ per month tax included

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!

Monthly subscription

€4.50 per Month.

4.50 € (3.75 € excluding tax)

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!