.223 Remington – 5.56 – 5.56×45 – 5.56 NATO: A Technical and Standard story

Note to all the Smurf people: the subject we are going to address here is complex by certain aspects and can be tedious to read sometimes. Prepare some aspirin and other (but legal!) doping substances. In addition, it is necessary to be clear with the notions of “calibers” and “ammunition”… and logically and to avoid too much repetition on the site, I refer you to Chapter 4 of my book “Small Guide For Firearms”.

At the root of the problem…

Before getting to the heart of the matter, let’s still recall a basis: the design or adoption of a firearm meets a “need” that may be:

- “Unique”, for example for military or administrative use: the weapon has a defined place in the framework of the organization of combat or law enforcement.

- “Multiple”, for example for civilian use: the weapon potentially has very varied applications (hunting, recreational shooting, sport shooting, defense…).

This need is expressed in a “specification” (by the manufacturer or by the customer depending on the case) which will determine several points and often in the first place: the caliber.

Originally, the “caliber” refers to the diameter of the barrel (in between lands or grooves depending on the case, often approximately … which ultimately doesn’t matter here!). By extension, it is associated with the length and morphology of the chamber, thus obtaining a “commonly accepted” reference: it is the “nominal caliber”. Be careful, the thing is in no way standardized in a “universal” way at the time of writing, a point that we will develop later.

Once the caliber is selected, the weapon will be associated with one or more ammunition (understand here, set of elements with precise technical data) according to the case:

- From a military point of view, the thing is often “simple”: there is a limited number of “loads” (for a limited number of weapons), whose data are known (or at least, can be known) exhaustively and which are (normally…) included in the specifications for the development (or off-the-shelf buying) of the weapon. Be careful, if the thing is normally simple to circumscribe, it is not uncommon for the incompetence or ignorance of certain “actors” or “decision-makers” to lead to totally inadequate purchases… We watched (helplessly… because it is useless to scream alone in the wilderness…) it happen several times during our administrative career!

- From a civilian point of view, the thing is much more complex, because the manufacturer does not know the ammunition that will be used in his weapon according to its use and the desires of its owner. Therefore, the manufacturer can or must (depending on the country) refer to a current standard for criteria of solidity (weapon) or pressure developed (ammunition) and can only make recommendations to his customers. After that, “alea jacta est“.

The other parameters (operation, feeding, dimension …) of development of the weapon go on like this next, but we will stop there so as not to pollute the subject.

This foreword being posed, the eternal question of the “differences” between the 5.56×45 and .223 Remington thus finds answers in three points: historical, technical and normative.

A problem of standards

It is important to begin by focusing first on a reality: the lack of a universally recognized standard for the manufacture of small caliber weapons and ammunition. By “universal” we mean that it would be recognized and applied by all, in countries all around the world… For the rest of the universe, we’ll see later.

A “standard” is a collection of technical data which makes it possible to manufacture a product in a “uniform” way, at least on a number of criteria. For example, while the CIP standard defines precise dimensions for the diameter of projectiles, it does not state anything about its weight.

From a civilian point of view, the small arms industry refers mainly to two standards:

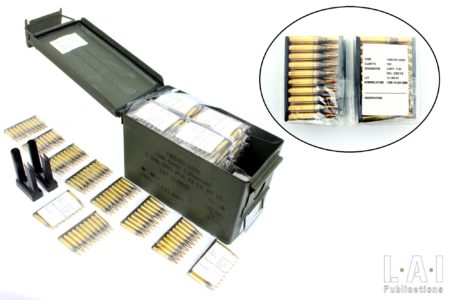

- The CIP, for “Commission Internationale Permanente pour l’épreuve des armes à feu portatives” (Permanent International Commission for the Proof of Small Arms). International, it includes several (but not all) European countries plus a few non-European countries. However, this standard is not “European”, but “International”. In the acceding countries, compliance with the standard is mandatory for the marketing of weapons and ammunition, but only in the civilian sector. The administrative sectors (armies, police…) are exempt, although they sometimes choose – for procedural comfort – to comply with it… without sometimes really understanding the ins and outs! The ammunition boxes (secondary packaging) normally bear the logo of the Proof House having tested the manufacture (Pic.01).

- The SAAMI for “Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute“, a voluntary standard existing in the United States.

It is imperative to understand the following point in this regard: if these standards do establish a certain number of data (dimension, proof pressure, maximum average pressure developed by the ammunition marketed …), they guarantee little with regard to what should be described as “ordinary use” by the shooter: the standardized weapon chambers and fires a standardized cartridge under conditions of total safety. That is to say, with a commercial cartridge that complies with the standard, a weapon that complies with the same standard will not “explode”… That’s not bad, isn’t it?

Apart from this insurance, no other factors are guaranteed: the mechanical operation, accuracy, lifetime of the barrel and mechanical parts, for example, are not established by these standards and their tests. By extension, it does not normally guarantee the legal classification of the weapon… But that’s another topic!

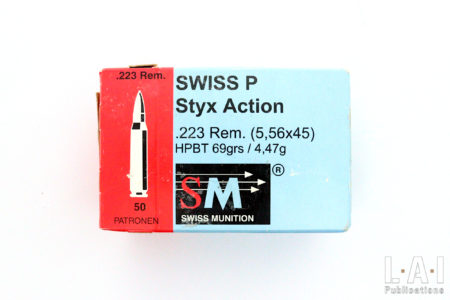

Therefore, it is not absurd to see a semi-automatic weapon being duly tested when a production flaw would completely exclude a semi-automatic rearmament: the proof does not guarantee operation. Ditto for ammunition, these standards do not establish a minimum “power” guaranteeing the operation of a weapon. It is really difficult to do otherwise: the civilian arms market being very diversified in terms of demands, how can we demand very restrictive standards? For the same caliber, some will want, FMJA bullet with a metal core (usually lead, sometimes with a m... More, soft-point, hollow-point, lead, light, heavy, subsonic or even short-range training cartridges, to shoot them into semi-auto weapons, bolt-action… for hunting, long range shooting and often to shoot “cheap”!

It would be comparable to have any type of fuel in our fuel stations, ordinary of course, but also at the pump, fuel for RC model, dragster, Formula 1 etc. The only guarantee provided by the institutions is: the vehicle will not explode… (or catch fire…)

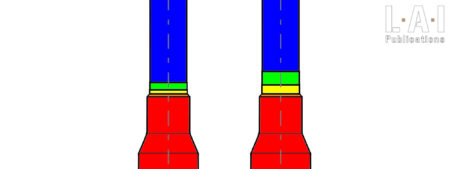

From a military point of view, in addition to the generally complex and relatively exhaustive specifications specific to each weapon – which can be considered as “micro-standards” – there is a multinational standard for NATO member countries. This concerns many “Western” countries adhering to NATO, but also by extension, many countries not adhering to the alliance, but using the same material for ideological, geopolitical or economic reasons (Pics.02 and 03).

This NATO-issued standard is intended – in the case of small arms – to provide guarantees of safety and interoperability with obvious logistical concerns. Here the standard is very restrictive (as often in military matters), because it defines a large number of parameters (with margins obviously): size (guarantee of chambering), maximum average pressure of ammunition (safety and operation) including under various temperature ranges, minimum pressure at the gas port (to guarantee the operation), primer hardness, etc.

Annual subscription.

€45.00 per Year.

45 € (37.5 € excluding tax) Or 3,75€ per month tax included

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!

Monthly subscription

€4.50 per Month.

4.50 € (3.75 € excluding tax)

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!