A Free Man

Extraordinary circumstances reveal a man to himself. Coming out of everyday life, but this is perhaps the hardest of the struggles, few of us will commit to a cause other than earning our daily bread or taking care of our family. A revealing generalized conflict puts everyone in front of their destiny. Some take it head on at the risk of their existence, then choose a side by offering themselves body and soul. Going through the ordeal of war and then the more insidious test of time, there are still some witnesses of this highly troubled human adventure. If some can choose the fight of the shadows, others will find in the skies a field of honor fit for them to express their greatness.

The Witness

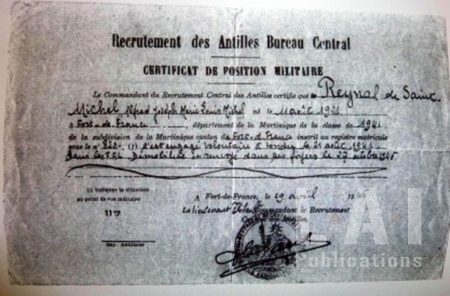

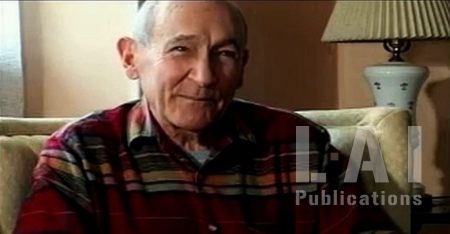

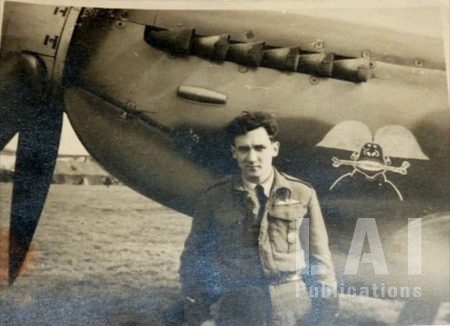

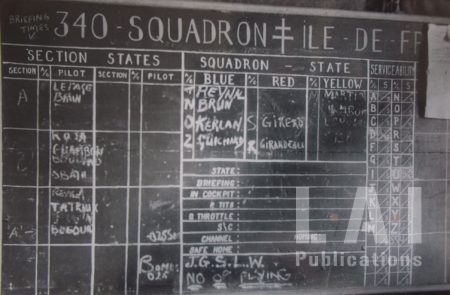

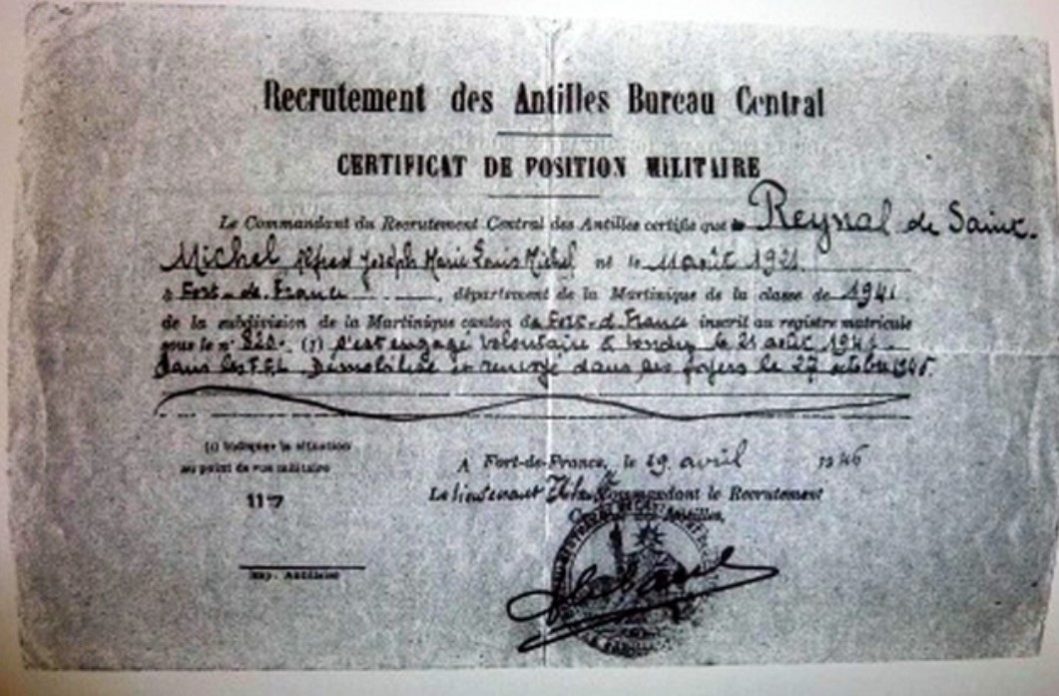

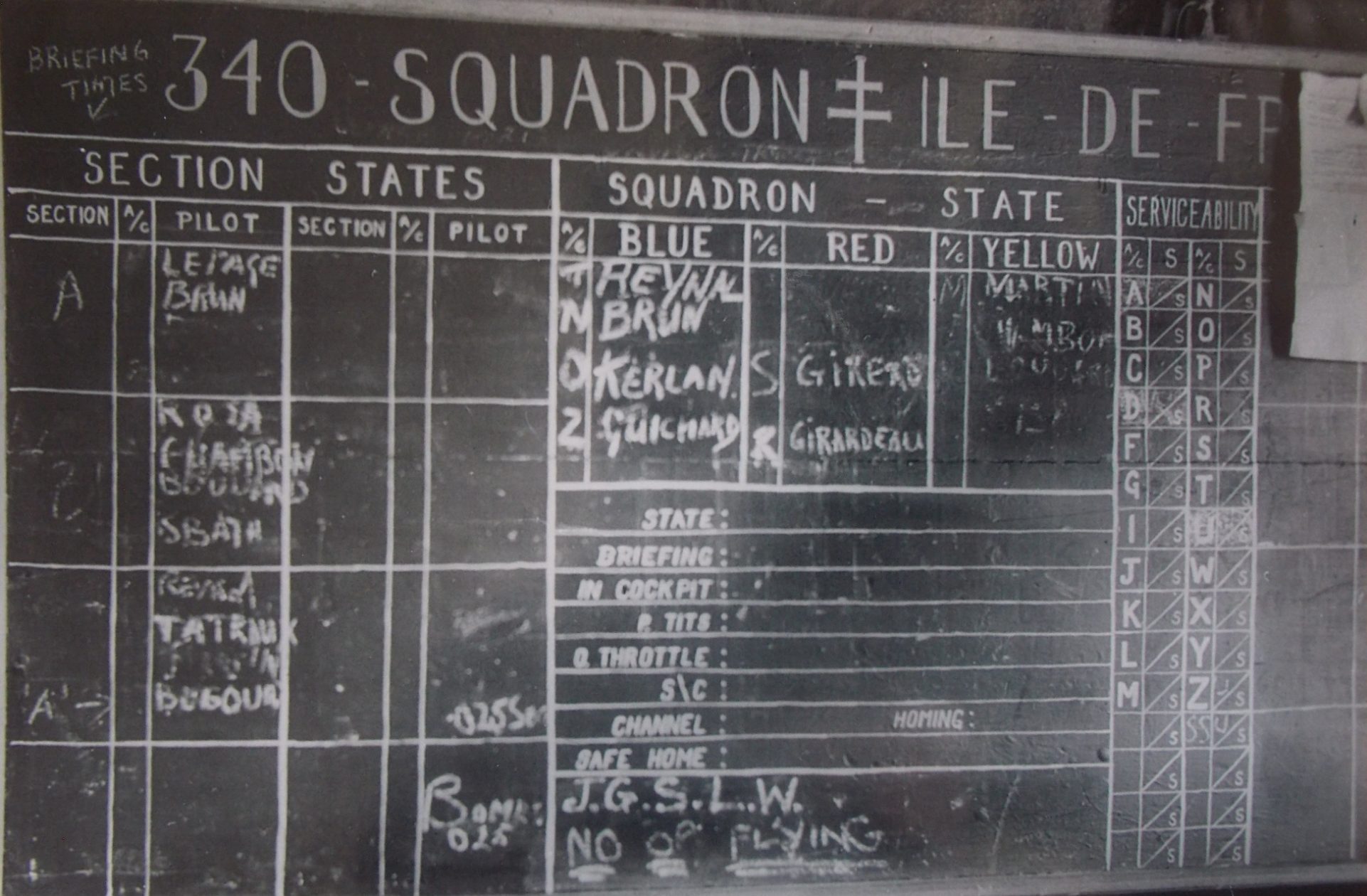

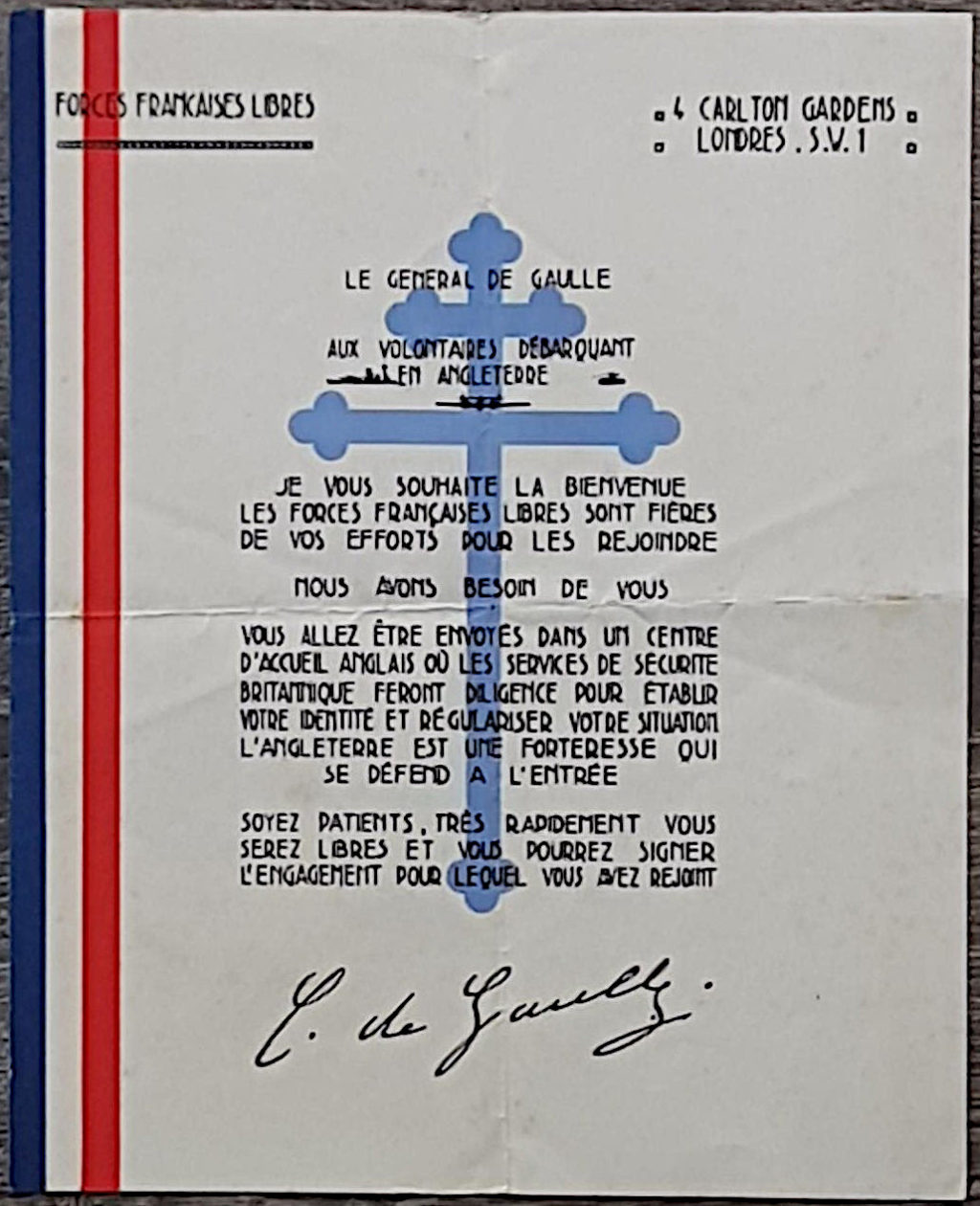

Born on August 11th, 1921, in Fort de France in Martinique, Michel de Reynal de Saint Michel enlisted in London in the Free French Air Force (FAFL) on August 21st, 1941. His registration number was FAFL 30.815 (Pic. 1). Germany, on the rise after shaking up Western democracies, had embarked on a victorious battle of annihilation towards the East. Assigned on the same day to the flight school, Michel would leave as a licensed aircraft pilot No. 243 GB on January 23rd, 1943, with the rank of sergeant. But he still had to play the game (Pic. 2).

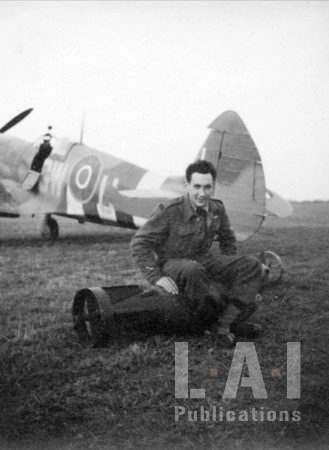

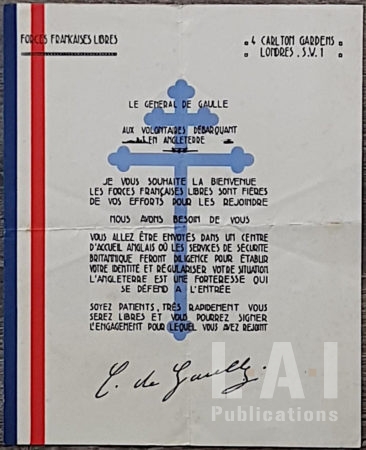

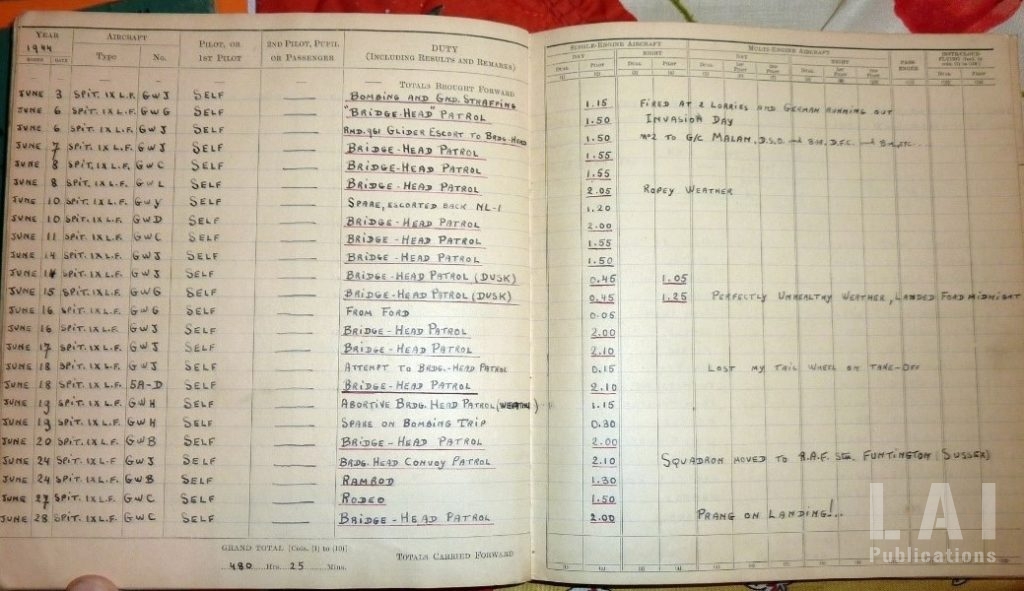

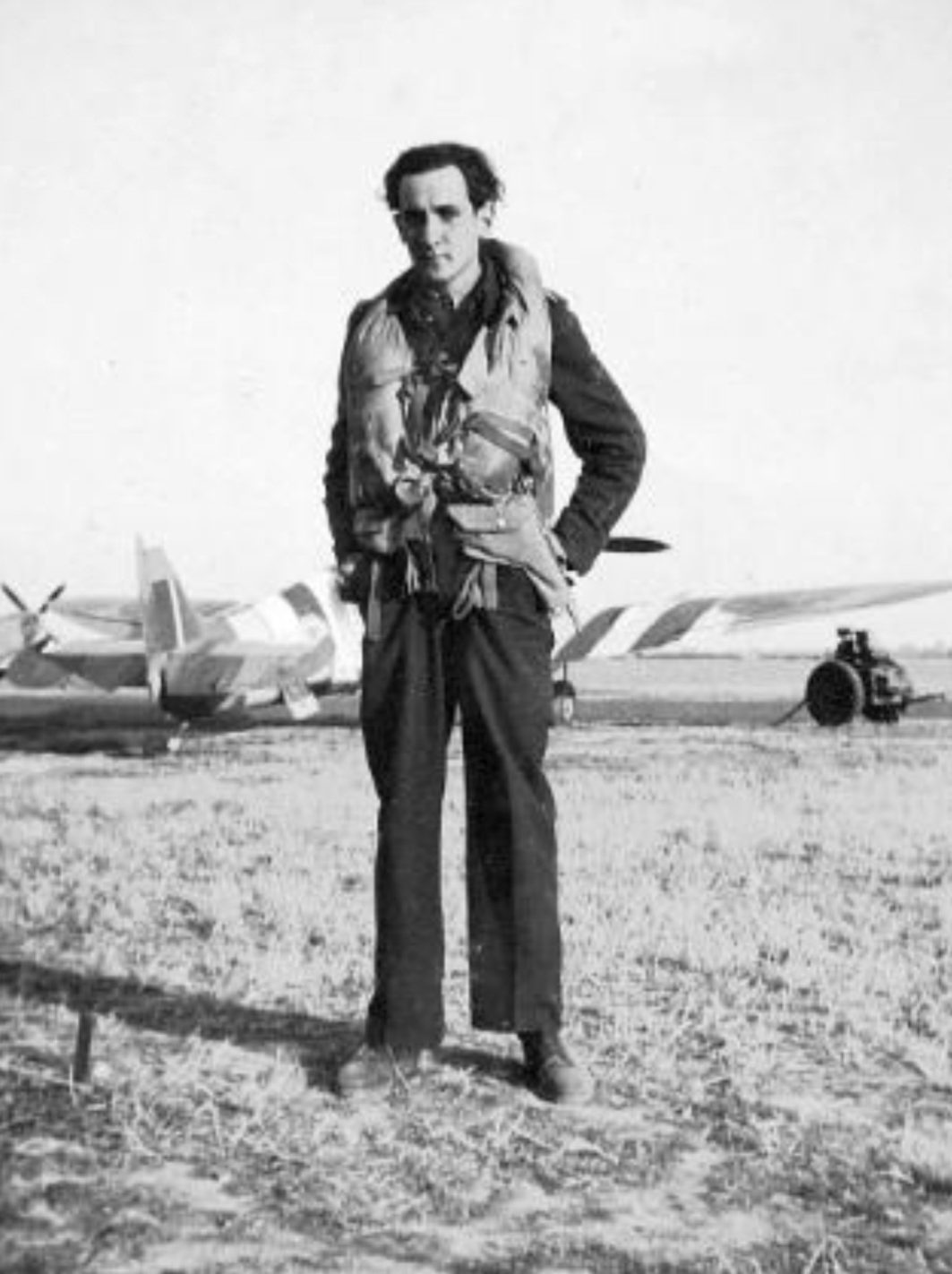

From a literary background with A-levels in philosophy, nothing seemed to predispose Michel Reynal to the scientific career of engineer he undertook after WWII at the National School of Electrotechnics and Hydraulics of Toulouse which since 1907 had trained engineers at the highest level. He spent three and a half years in Australia participating in the hydraulic installation program (Snowy Mountains Authority) and then 35 years working for Michelin, 11 of which in the USA would fill an active life. Hearing the call of General de Gaulle and he was eager to join the Free French Forces: The Battle of Britain “made me dream”. (Pic. 3). Once there, the opportunity to become a pilot arose. Training began immediately. Michel spent 15 months of training to fly on “Tiger Moth” and had a first flight at a low-level altitude “absolutely exhilarating” on a Boeing T-6. He would then fly on a British Miles Master before taming the famous Spitfire which served during this period of WWII (type I, II V IV and XVI). Let us hear it from him. (Pic. 4)

The Men

“I have the utmost respect for the RAF, its organization, its competence, its sense of humor, its calm and its ‘understatement’, in the literal sense of ‘euphemism’, if not the fact being able to soften a harsh reality with words. The civilian population, very welcoming, patriotic, with a sense of humor even facing the worst circumstances. Very few … Black market (!). As of the Germans, necessarily frowned upon at the time, after the bombing of England? I didn’t have an opinion, but I shared the general opinion.” (Pic. 5)

“With very few exceptions, the relationship between pilots was excellent and improved more and more with time and as the number of operations increased. The atmosphere in the Dispersal was very relaxed, we often flew with a civilian outfit in case we were shot down into French territory. I still remember Commander Fournier admiring an absolutely crazy shirt that I proudly wore: “de Reynal, you have such beautiful pajamas”. As for service and flight: discipline was all the stricter as it was voluntary. My cousin René with whom I had left Martinique clandestinely, was a machine gunner on B-25 in the Lorraine group. I think he had much the same atmosphere in his squadron, an atmosphere that he probably improved even more, because he was very keen on jokes. I had no relationship with Normandie Niémen. I just quickly knew Monier called “Trompe-la-mort” (TN: Daredevil) with whom I had an accident that motivated his transfer to this hunting group. He was an excellent fighter pilot who had some spectacular accidents and covered himself with glory in Russia.”

About René Mouchotte, a FAFL figure shot dead on a mission on August 23rd, 1943: “I saw him very little during my short stint in the Alsace group. I had been led in front of him because someone had snatched my bicycle at the mess, perhaps by mistake, I had taken another bicycle at random to return in time to the Dispersal. It was theoretically a “crime”. Mouchotte only smiled as he raised his shoulders.” (Pic. 6)

The Machines

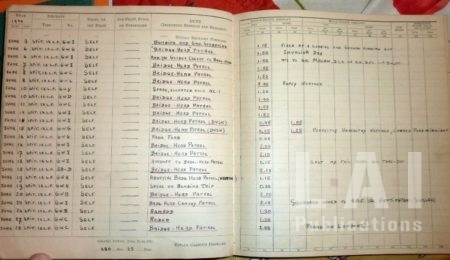

About the Spitfire: “I had the chance to do two flights on the first day. It was a delightful aircraft to fly especially the Spit 1 which had reasonable power. It was also the opinion of the Germans who had been able to obtain a copy abandoned in France at the debacle. After the OTU (last flying school), I had been assigned to the Alsace group installed in Biggin Hill where I had been able to try the last model, the Spit IX LF. My despair was great when, the group having too many pilots, I was transferred to Île-de-France then in reformation in Italy, near Ayr. (Pic. 7) My first flight on an old Spit V ended quickly as I experienced an engine failure on takeoff. I had the chance to land the plane on its belly in a small, ploughed field surrounded by walls. Minimal damage was done to the plane, but it was necessary to look for a replacement near Edinburgh. The next day I boarded as a passenger in a Tiger Moth piloted by Monier who flew all the way close to the ground. I was in the front seat and saw the high-voltage line, but I couldn’t react, because I thought Monier wanted to go underneath. Spectacular shock. Monier only bit his tongue, but I was taken to the hospital for shock and a nasty knee injury that took 7 weeks to heal.”

“My second accident took place at the end of 1944 in Biggin Hill where Île-de-France had been put to rest after the engagement in Holland. We had Spit IXs HF capable of flying at over 40,000 feet (12,000 m). We “top covered” American B-17s as we escorted them over the Rhur. In order not to lose our touch, we would sometimes shoot at targets on the ground at the mouth of the Thames. After one of these shots, I saw that my oil pressure is at zero. I “phoned” that I would try to land on a nearby airfield, but on the way, internal mechanics went South. After doing what was necessary, I showed up to land in a small field lined with trees. I woke up 3 days later in the Canterbury Hospital. I had absolutely nothing and got up to go to the bathroom, followed by a crowd of nurses. As for the aircraft, it seemed that it had lost its wings and that the fuselage had made several barrels. The investigation found that the oil radiator had been punctured by a tree branch, not those on the crash site. As I didn’t fly at a low-level altitude, the question remained …” (Pic. 8)

“I arrived in operation at a time when superiority was already established. The Me 109 and Fw 190 attacked by surprise and did not seek combat. I think it was especially the maneuverability of the Spitfire that impressed them: they had to act by surprise. It was when we started to fly the Spit IX LF, I believe, that it happened. Before that the Spit managed to keep up with the Me, but the Spit V had problems with the Fw”. (Pic. 9)

“My first combat flight was a SWEET in Spit V, entered in France through Cherbourg. We were then stationed at Perranporth in Cornwall and regrouped with other RAF squadrons at Church Staton. The German chase didn’t wake up, luckily for me, as my engine started to run roughly, and I lagged behind the group for a long time before I could catch up. Thereafter as long as we did pure hunting, we were disappointed by the Germans who were hardly seen when we were escorting the bombers. They sometimes came out of the clouds and left quickly by the same path when we faced them. The only time I saw them up close was when two of the bombers we were escorting to Germany lagged behind the formation. We sent two fighters to escort them, and they were attacked by 12 Me 109. Our group became interested in the case and Colonel Sammy Sampson had a “Me” and I got another one, but only probable because I had forgotten to plug in my camera. Commander Massard was shot down, but he parachuted, and I had the pleasure of having lunch with him after the war.” (Pic. 10)

“I only had one quite long fight where I saw a “Me” shoot a long burst pointed directly at me at 90 °, without taking my speed into account: I felt perfectly safe. I think the German pilots lacked training at the end of the war probably because of a lack of fuel for the schools. The RAF pilots were well trained and had gyroscopic points that made it possible to reach their targets at every opportunity. It should also be noted that the behavior of the Spit was impeccable in tight turns near the ground. It was not the same for the FW 190: that’s why the German pilots favored the “Me”.”

“Our state of mind was excellent; we were only a little disappointed by the lack of partners on the German side. On the other hand, the ground attack proved to be exciting. Sure, there was the DCA (20 mm quadruple), but it was the treasure hunt: locomotives, trucks, cars, motorcyclists, …. There were also dive bombings as well as low-level altitude bombings. (Question from the author: What about the use of amphetamines?) You don’t need it when you’re young, fatigue passes quickly, and excitement is dangerous when you need calm and precision.” (Pic. 11)

About sky combat: “The US B-17 and B-24 bombers determination was impressive. The matte black painted RAF’s Lancasters and Halifaxs were intimidating to escort in broad daylight, the RAF’s mosquitos incredibly fast. The Gloster Meteor with which we “dog fighted” for experience, was also very fast but easily defeated during turning maneuvers, which was verified with the Me 262. Spitfires have shot them down more than the reciprocal.” (Pic. 12)

Between two flights (a striking memory): “It was at the time when we top covered the American B-17 over the Rhur. We had the Spit IX HF which could fly very high, but only had 85 Imp. Gallons (385 liters) of gasoline. So we were carrying an additional 90 Imp. Gallons (408 liters) tank that we had to drop in case of combat, but which delayed takeoff and made the plane difficult to fly. We left the night before from Biggin Hill to land in Manston near Canterbury located as close as possible to France. The runway was wide and long, used to receive damaged bombers returning from mission. In the morning at dawn that day, we took off in a line of 12 planes, taking advantage of the width of the runway, so as to save time on the regrouping with the other (Australian) fighters who were in the game. The weather was slightly foggy, but at about halfway through we saw 12 Spits coming in front of us identical to ours. What to do? We were both at full speed, and it was impossible to stop before the collision. So, we kept flying on, us below, them above, but it was close! … this would have made quite a firework with 19032 liters of gasoline. I still think about it sometimes.”

D-DAY

“We were informed in the afternoon of June 5th with a defense to leave the base. The planes had been marked with white stripes 1 or 2 days before and had not flown since (Pic. 13). We were very excited with the prospect of descending a lot of “Huns”. Woken up at 3 am we took off in the very early morning. Unforgettable show! Mass of warships, landing craft, open and empty gliders in the fields. The flames escaped from the battleships bombing the German fortresses. On the other hand, not an enemy plane, we were only attacked 3 times by a Mustang probably American. Each time the fight engaged, the Mustang flew away, then an English voice, very calmly said: “That was the third time he attaked me, I had to shoot him down”. I’ve never been able to know what may have happened, but no more Mustang.” (Pic. 14)

“In the afternoon, I returned over the D-Day landings, as a wingman to Colonel (Wing Commander) “Sailor” Malan, the first English ace of the war. The sky was obscured by gliders towed by Lancasters. No enemy hunting groups anywhere. Equipment was beginning to land in limited areas. The following days, we were regularly on guard duty, flying over the daytime landing. A test was done at night, very trying for us, despite the makeshift device to hide the flames of the exhausts. Clouds and rain, landing on another base at midnight. After several changes of base of operation and after we had settled in our tents, we finally landed in France, on July 9th, 1944, to return the same day to England. After that, we started the fighter/bomber work from B 8 (Bayeux), B 29 (Bernay), B 55 (Courtray). After that, “resting” in Biggin Hill. Then we returned to hunting / bombing at B 85 (Holland) with Spitfire XVI on February 1st, 1945, and finally B 65 (Lingen Germany) on April 16th, 1945″. (Pic. 15)

“The outstanding personalities for me: Bernard Trouillet, Claude Rosa, Félix Lagarde, Christian Chapman, Lt Guignard, Cdt Massart, Cdt Hardy, Cdt Fournier, Group Captain “Sailor” Malan, Wing Commander Alan Deere, Wing Commander Sammy Sampson. I have not seen Generals Valin and d’Astier de la Vigerie and have hardly thought of them. At the Liberation, the state of mind for me was very bad. The day after the Armistice I was rushed back to Paris on the pretext that I was late for a rest. I was disembarked in a barracks of “resistants” in Neuilly without a penny of French money. Later, fortunately I was hosted by a cousin in Paris while waiting for my return to Martinique. I didn’t expect so much to survive and I was worried about the future? I did not experience the Liberation of Paris, but I think the joy was greater than during the armistice that took place long after in a foreign country. I had an unfailing admiration for General de Gaulle throughout the war. We only deplored that he was surrounded by less recommendable people. After the war, with the Evian Accords and the episode of the Algerian Independence War involving the Pieds Noirs (Black Feet) and the Harkis, I had the very clear impression that he fell, out of pride, into the hands of even less recommendable people.” (Pic. 16)

About the current era: “According to Winston Churchill’s memoirs, the war of 39-45 could have been avoided, but perhaps not for long. In any case, the weakness of our Defense could only attract lightning. I do not think we have learned the lesson. In addition, more or less controlled immigration would weaken our will to fight. Conclusion: with our type of government, not much to hope for. Resignation is necessary.” (Pic. 17)

What’s more to say?

From this personal testimony, it is clear that little was to be said in the words of a pilot claiming to be anonymous among “so many” others. With 181 war missions in 281 hours of operational flights, five citations (silver stars, bronze stars, two palms, one vermeil star), the Croix de guerre 39-45, the Médaille Militaire, the Légion d’Honneur, the Médaille de la Résistance et des évadés as well as the Distinguished Flying Medal will be enough with the Ordre National du Mérite for his active engagement in the Reserve until 1969 when he finally resigned from the corps on theJanuary 1st, continuing to fly on piston-engined aircraft. Our Elders always had their own way of evoking their commitment, saying that they had done their “job” or what they deemed right to do or what they simply called “not much”. Staying alive. A simple task to accomplish. Obey. So what can we do to simply say thank you? Listen, understand and above all transmit. In the end, very little compared to what has been done. To forget would be the true Evil. Have a nice flight!

Commander René Mouchotte (a fragment of his will) “If fate grants me only a short career as a commander, I will thank heaven for having been able to give my life for the Liberation of France. Let my mother be told that I have always been happy and grateful that I have been given the opportunity to serve God, my country and those I love and that, whatever happens, I will always be close to her.” (Pic. 18)

Michel de Reynal de Saint Michel took his last flight on August 15th, 2021, at 9:30 am, the day of the Assumption (from the Latin ascendere … rise!). Durnig Michel’s burial, the Colonel of the Orange fighter squadron, flying a Mirage 2000 came to ensure its high coverage by making two passes for a cross as noisy as impressive above the church. The Air Force does not forget those who made its history. (Pic. 19)

Pierre Breuvart

During “lockdown”, Michel de Reynal drew the plans of an engine of his invention …

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!