Desert Eagle : from Hollywood to the shooting range

This appetizer with the excellent movie Last Action Hero (starring Arnold Schwarzenegger of course) highlights two interesting points: American cinema has largely contributed to the myth that the Desert Eagle has become, and no, this semi-automatic pistol was not designed as an anti-material weapon for roadblocks in Israel… But more on this later.

Once upon a time in the 1980s

The Desert Eagle fascinates in many ways, including the fact that it is the most “powerful” semi-automatic pistol at the time of writing, at least tied with the Larz Grizzly and the Automag V, that are less known and distributed. While the .50 Action Express (known as .50 AE) cartridge made the weapon popular, it should be remembered that the gun was originally designed to fire the .357 Magnum.

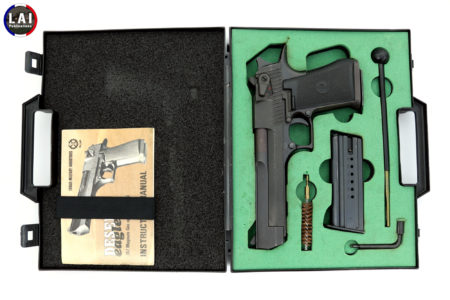

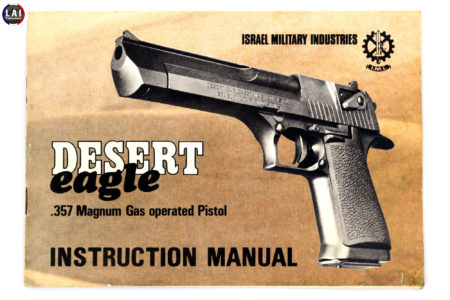

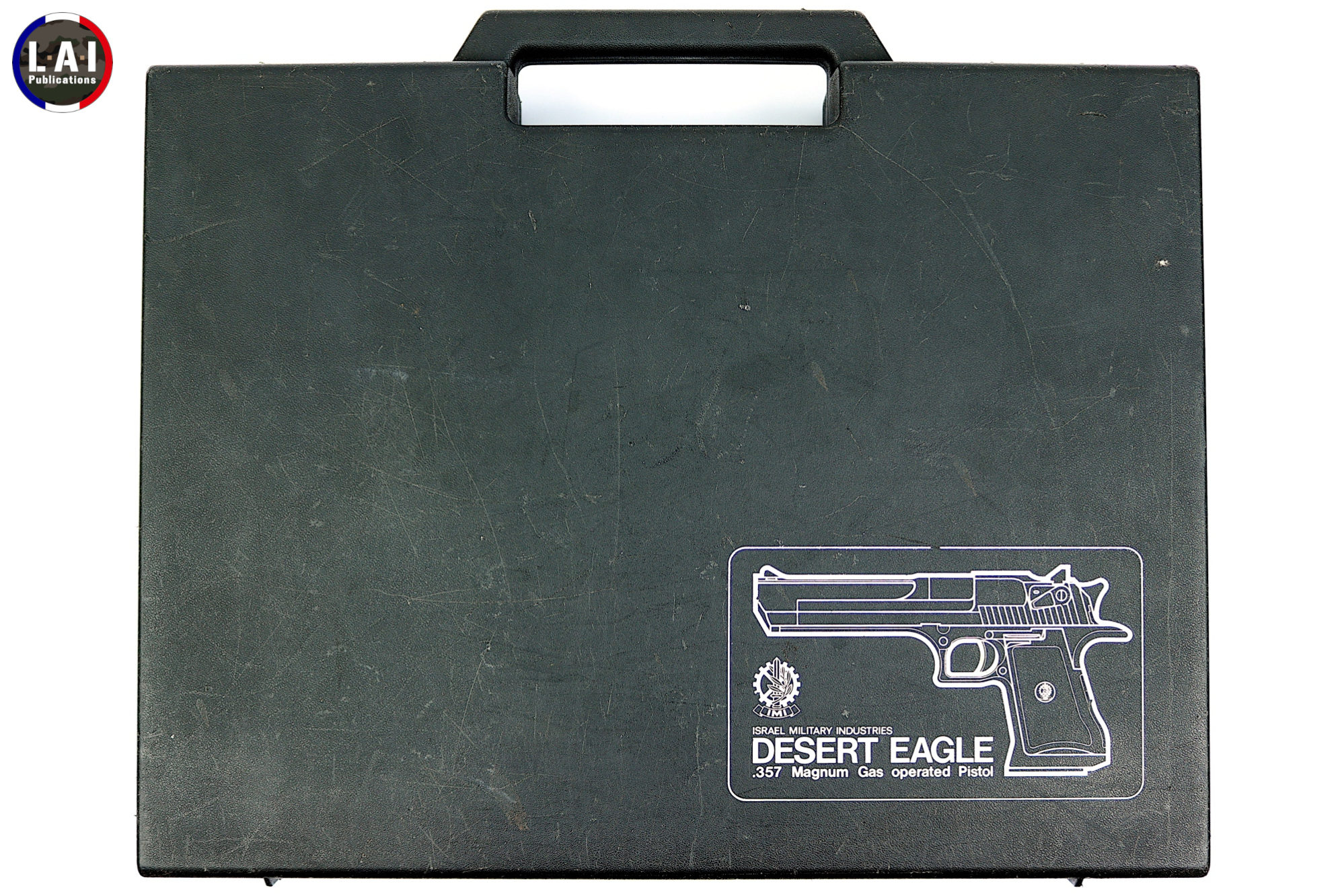

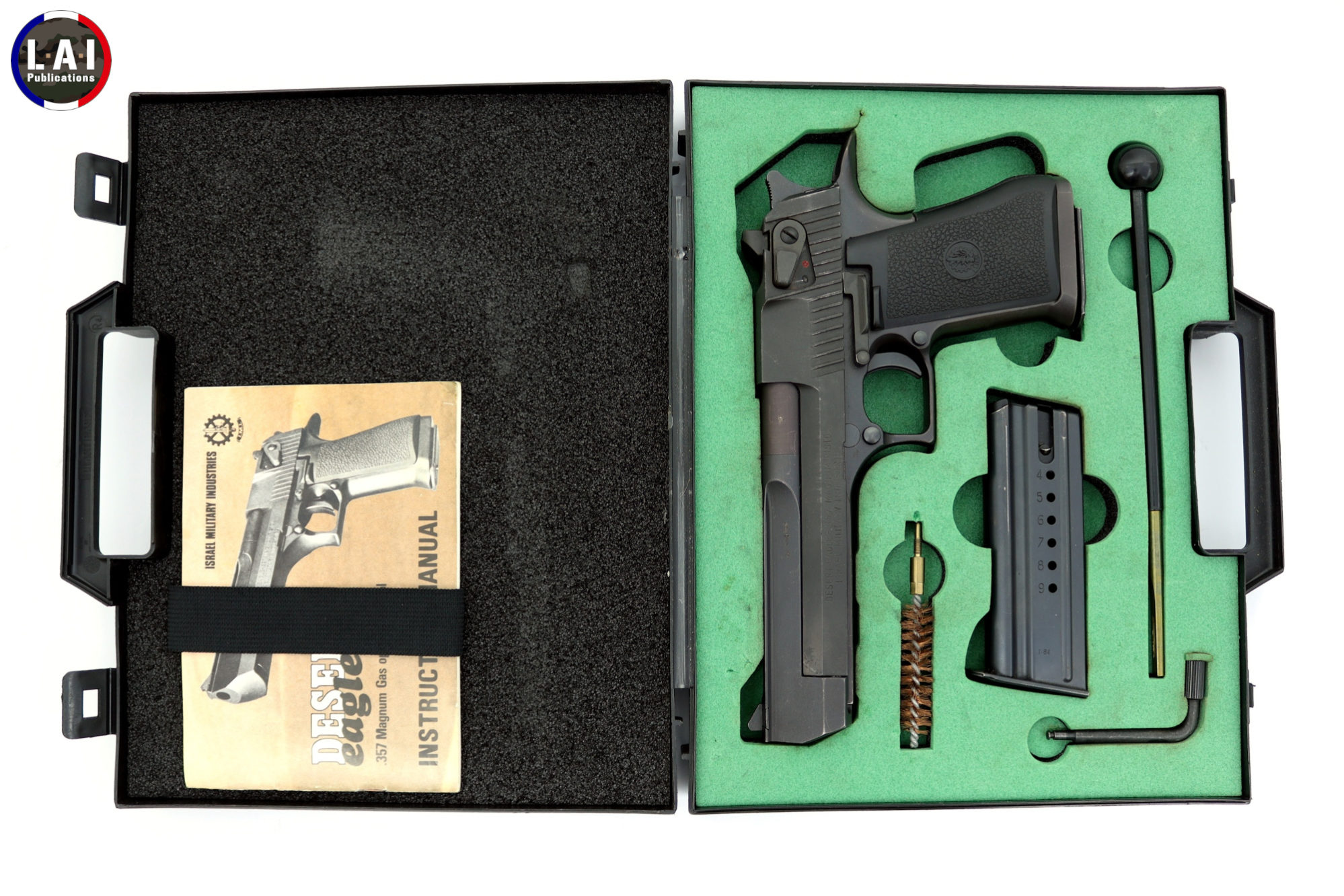

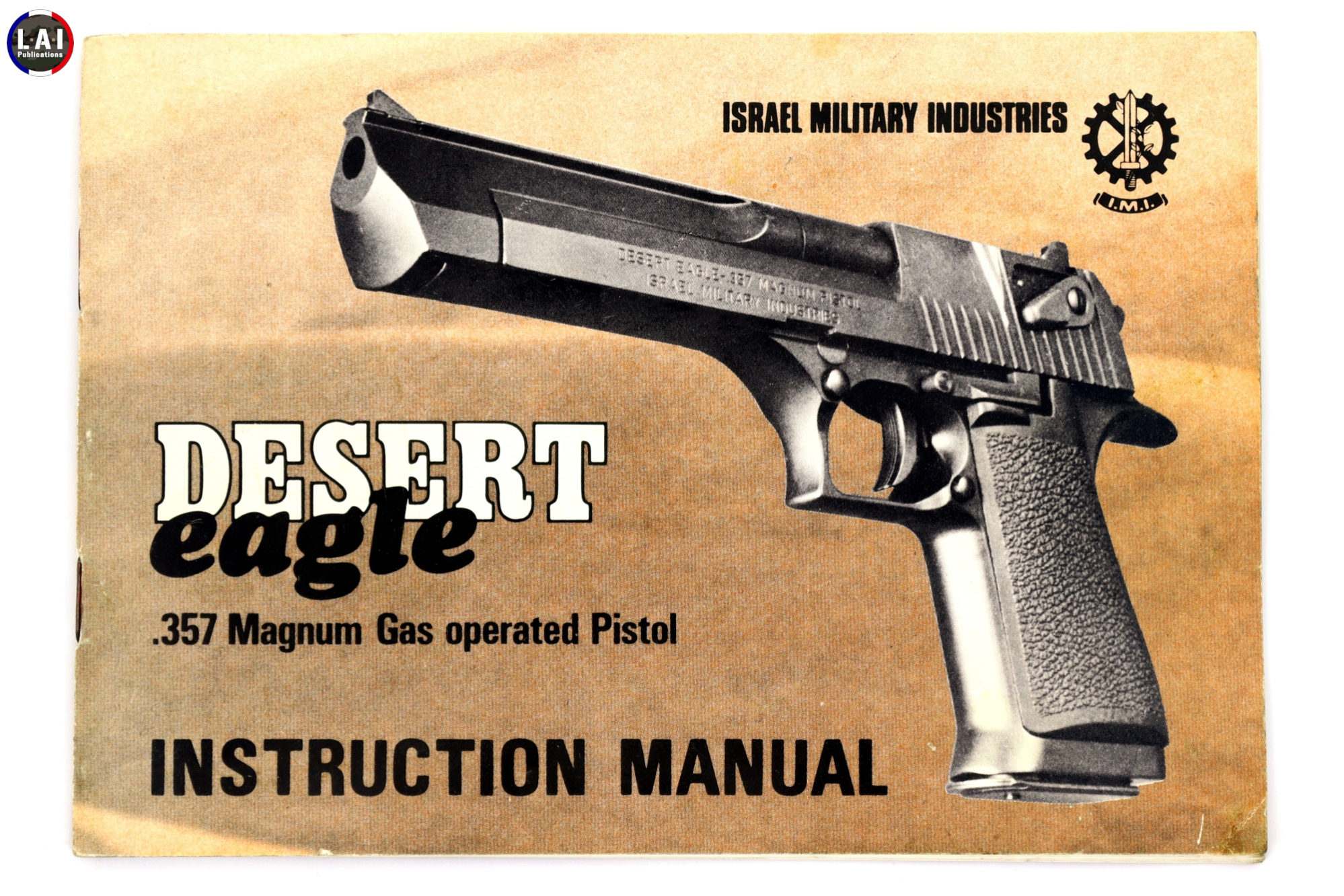

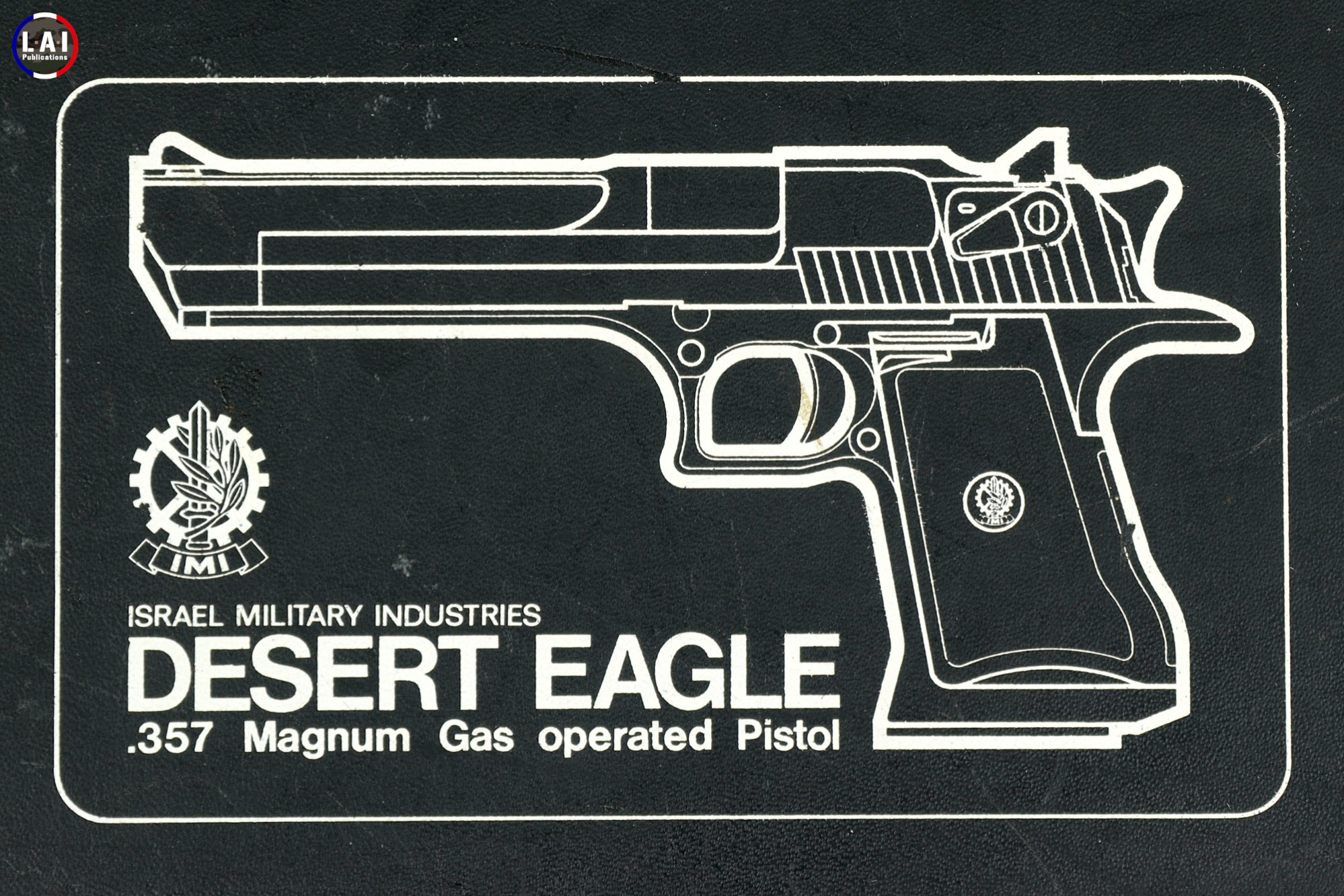

The American company Magnum Research, Inc. (MRI) was founded in 1979 in Minnesota by Jim Skildum and John Risdall (as indicated on the manufacturer’s website). A certain Bernard C. White drew up the plans for a gas operated pistol that was presented for the first time at the Atlanta S.H.O.T. Show in 1982. Arnold Steinberg’s name often comes up as co-author of the patent in articles published on the Internet, but we have not seen any trace of it in official documents. The drawing shows the basics of the future Desert Eagle with the multi-lugs rotating bolt, ambidextrous safety and the characteristic slide. The first .357 Magnum pistols manufactured by MRI, called “Eagle”, were released the same year, but they suffered from reliability issues (advertising can be seen in the link here). Indeed, the problem is that the .357 Magnum cartridge, initially designed for shooting in revolvers, has a rim which makes its use in a semi-automatic pistol complex. It was then that Magnum Research, Inc. turned to Israel Military Industries (IMI, now renamed “Israel Weapon Industries” or IWI) to improve its pistol and produce a very first series of 1000 weapons. The connection between the two companies is not really known… legend has it that the two film producers Menachem Golan and Yoram Globus (the famous “Go-Go Brothers”) helped with the connection because they were looking for a “peculiar” weapon, “a face” for their B movies… (1). It just seems more logical to believe that MRI was looking for a subcontractor capable of improving and manufacturing their pistol. A new patent, designed by Ilan Shalev of IMI, was filed in 1985. It was this patent that gave birth to the first real “Desert Eagle” Mark I, first in .357 Magnum, then very quickly in .44 Magnum (Pics. 01 to 08). The pistol was therefore initially designed in the United States, but it was improved and produced in Israel.

We can then ask ourselves the question of the interest in wanting a pistol in a “Magnum” caliber at all costs? Aside from the purely technical challenge of creating the most powerful handgun possible, it seems that Magnum Research, Inc.’s commercial target has been metallic silhouette shooters and hunters. They probably didn’t imagine at the time that their weapons would be the delight of movie prop makers and thrill-seekers who love to explode watermelons on YouTube… Metallic silhouette shooting is a discipline that includes several categories, including shooting with a large-caliber pistol up to 200 m on animal-shaped gongs. Although it is surprising, the Desert Eagle seems to be used by some shooters because the weapon is accurate enough for it. This explains the availability, from the start, of several barrel lengths (interchangeable!): 6 inches (152.4 mm) being the “standard” length, but 10-inch (254 mm) guns will also be available, and even… 14 inches (355.6 mm)! As for hunters, we must place ourselves (we – French shooters) in the context of North America, where a chance encounter with bears may require the use of a powerful weapon compact enough for transport: today we find in this category a whole bunch of revolvers in extravagant calibers such as the .454 Casull. Some hunters also use it to hunt deer or elk because, as mentioned, the weapon is accurate and even on its early versions it has a 3/8″ prismatic rail on which optical or optronic sight can be mounted.

The pistol continued to be improved and was released in a new version by the end of the 1980s (maybe 1989 or 1990 tops), the Mark VII (Pics. 09 and 10). It was then marketed in .357 and .44 Magnum and was then completed by the .41 Remington Magnum (10.4×33 mm R), whose production ceased very quickly. The Mark VII is easily distinguished from the Mark I by the shape of the safety levers that change, becoming more prominent. Also, the IMI logo is placed on the pads.

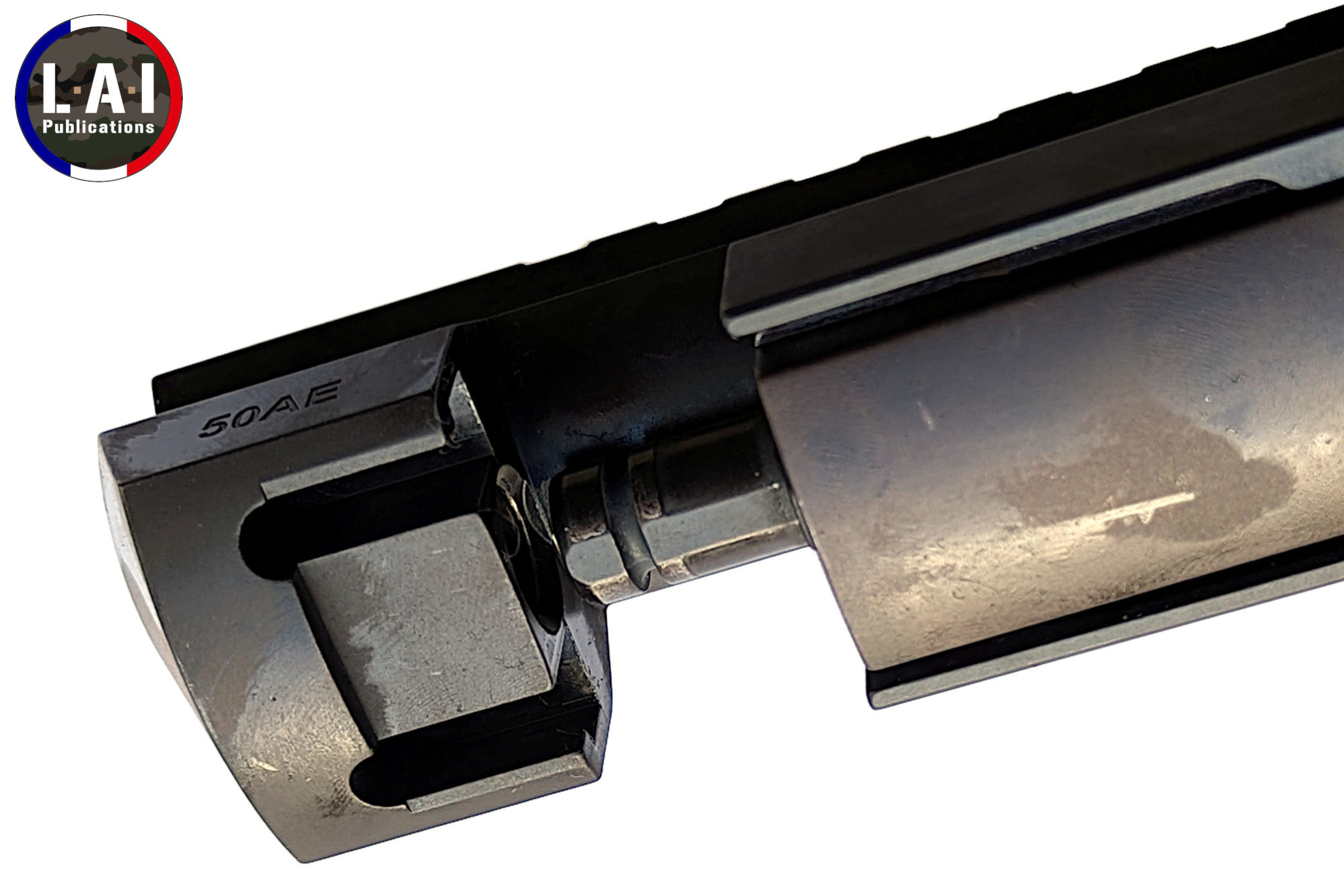

In 1988, the famous .50 Action Express cartridge appeared. Announced for the Desert Eagle in 1989, it was marketed for Mark VII at the very beginning of the 1990s (probably 1991). This caliber allowed the Desert Eagle to simply rise to the top of the podium of the most powerful semi-automatic pistols in the world. The birth of the .50 AE was not without pain, however: because of federal laws, offering a weapon with a caliber greater than .500 inches (12.7 mm) on the U.S. civilian market comes up against some restrictions… Yes, even there! The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (BATFE or often just “ATF”) classified such weapons as “destructive devices” (i.e., in the same category as grenade launchers, for example), which, in some states, prevents their sale to civilians who do not have the appropriate federal license. However, if the barrel used to develop the caliber, equipped with conventional rifling and designed around a .510 inch (13 mm) bullet, passed the ATF test (a .50 diameter gauge should not pass through the said barrel), the same was not true with the polygonal bore barrels of the Desert Eagle! Magnum Research, Inc. had to adapt it by reducing the bullet to just .500″ (12.7 mm). This results in a slight taper of the case before its collar (about 0.2 mm in diameter). Another interesting point is that the ammunition uses a base with the same dimensions as the .44 Magnum, which makes it compatible with the bolts adapted to this caliber… which is the case with the Desert Eagle! As the base is therefore smaller in diameter than the case body, the .50 AE is one of the most notable representatives (along with the .284 Winchester) of ammunition with a rebated rim. It should be noted that the arrival of the Mark VII in .50 AE caliber introduces the use of the Weaver rail in place of the 3/8” prismatic rail, but only for this caliber. This also results in a slight difference in the geometry of the slide: the one of the .50 AE is a little more “tough” on its upper part than that of the other calibers. The Mark VII in .357, .41 and .44 Magnum will keep the 3/8” rail and a slightly thinner slide on its upper part.

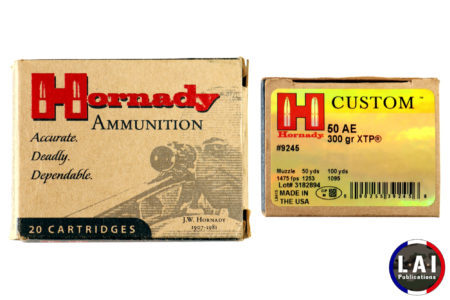

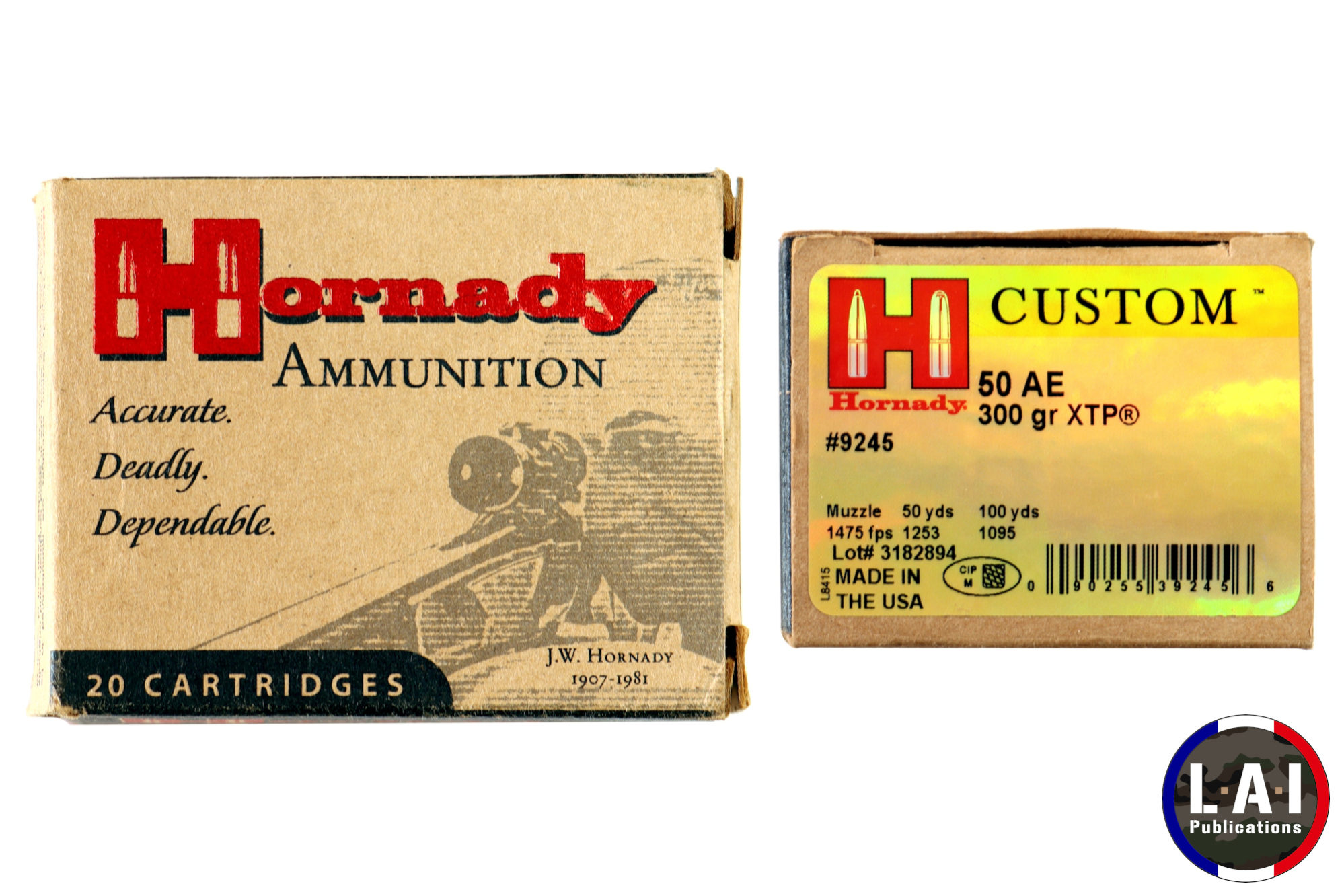

As far as the cartridge’s performance is concerned, if we base ourselves on what the Hornady box (which we used for our test) indicates: the 300-grain (19 gram) bullet exits the barrel at a speed of 450 m/s (1475 fps). The .50 AE cartridge is often credited to be the sole work of Evan Whildin as president of Action Arms and officiating as a “commercial”, but it is a joint work with Bob Olsen having a much more technical role.

Production at the Israeli manufacturer continued until 1995, to continue at Saco Defense in Maine (which has nothing to do with the Finnish firm SAKO). However, from 1998 the pistol was produced again at IMI / IWI in Israel without the reasons being known. Note that Saco Defense produced a few examples of the Desert Eagle in .440 Cor-Bon, a cartridge taking the case of the .50 AE but restricting the collar to accommodate a .44 Magnum bullet (to put it simply!).

In 1996, the Mark XIX appeared. Strangely, we have no idea what happened to the intermediate numbers between the Mark I, Mark VII and XIX! This model generalizes the use of the Weaver rail and the more “substantial” slide already found on the Mark VII in .50 AE caliber. The model thus reconnects with one of the “strengths” of the first Desert Eagle: offering to the consumer conversion kits with barrels and magazines for the desired caliber, all of which are perfectly adaptable to the frame and the bolt carrier group. As already mentioned, this is the case for the .44 Magnum and the .50 AE!

Production of the weapon will cease at IMI in 2009 and move next to MRI’s headquarters in Pillager, Minnesota (Pics. 11 to 17). It was at this time that the Picatinny rails replaced the Weaver rail. In 2010, Magnum Research was acquired by the Kahr Arms group and production continues today on American soil in a complete range of pistols in different configurations: barrel lengths, finishes and calibers. In 2018 the .429 DE appeared: this is a very similar concept to that of the .440 Cor-Bon: a .50 AE case reduced to the collar to accept .429 bullets (.44 Magnum bullet diameter), resulting in a cartridge with a 240-grain bullet and a speed of 495 m/s (1625 fps). We can also note the appearance of the L5 (Light 5 inches) and L6 (Light 6 inches) models, which are “lightened” versions of the pistol with the use of an aluminum alloy frame, reducing the weight of the pistol by nearly 500 grams.

So, let’s tackle the sore point here: was the Desert Eagle used as a service weapon in the Israeli army? No! It’s always fun to wonder how such rumors could have caught on… like the one that would make you believe that the Go-Go Brothers are behind the manufacture of the Desert Eagle in Israel! Could it be that the manufacturer launched it himself when his weapon was put on the market? After all, with the success of the UZI, it would have been rather positive to say that his pistol was also used by the IDF… Or was it the confusion between the DE and the “Baby Eagle”, its little brother the Jericho 941, derived from the CZ-75? Indeed, some productions of the 9×19 mm pistol have been marked “Desert Eagle Pistol” on the slide! Anyway, it seems really far-fetched that any unit or army has adopted this pistol. We can read on Wikipedia that the special units of GROM (Poland) and GOE (Portugal) used the weapon. However, the evidence is thin… It is quite possible that these units bought a few examples, for testing… However, their use in operations remains to be proven. It only takes one shooting session with the pistol to realize that this is quite implausible.

The ultimate “Pop” weapon

When you send a photo to non-shooter friends and write “look at this!”, there is no need to state the model of the weapon: everyone recognizes it. Like the AK-47, easily distinguished by anyone (except perhaps by some journalists… oops…), it’s impressive to see how the Desert Eagle has made its mark via cinema and video games… This gun has a “face”, and what a face: frankly impressive and photogenic, it has “worked” in more than 600 films! No need for technical explanations, the viewer immediately understands, given the size of the beast, that the weapon of his hero (or villain!) is out of the ordinary, more powerful than any other pistol. As a reminder, the Mark I pistol was released in 1985 and immediately appeared in the hands of Mickey Rourke in the film The Year of the Dragon, to immediately follow up with Arnold Schwarzenegger in Commando. The pistol seems to be of normal size in the hands of “Schwarzy”: in fact, it is perfectly in line with Mr. Universe’s build! He will obviously adopt it again as a service weapon in his role as a policeman in the excellent, wonderful, cult Last Action Hero (1993). The list of “roles” of the Desert Eagle is really very long and seems endless. We can note its appearance in The Matrix (1999) in the hands of Smith agents: yes, the Desert Eagle can also be the weapon of the “bad guy”! This was already the case in Robocop (1987): it is indeed the weapon used by Clarence Boddicker. And even today it is present in the hands of the super-anti-hero Deadpool. No, really, we are not about to see it disappear from the screens. Its appearance is often linked to the character of the film: an extraordinary character, an extraordinary gun! Finally, how can we not mention Snatch (2000) where the gun even holds an important part of the rhetoric of “Bullet Tooth Tony”… with a close-up on the (fake!) markings.

And what about video games? Counter Strike, to name just one of the most famous games, has made it very popular with players: it is a powerful and accurate weapon. Often, in games like Call of Duty, the Desert Eagle is given as a gift by unlocking experience levels and this, not to spoil anything, in a gold-tone finish (available in the catalog of real weapons!), marking the status that the gun represents: a rare, powerful and stylish weapon! Obviously, coming to the shooting range with a Desert Eagle, whatever its caliber, is sure to attract attention. And will have you hated by your neighbors who will be dazzled by the flames and shaken by the vibrations of the shots with .50 AE… This is where we see all the power of the image that has been reflected by pop culture. The Desert Eagle has no military aura, has not participated in any conflict, has not made any stunts and yet… Who wouldn’t want to try it on the range? One would almost dare to ask: is the Desert Eagle a marker of social status? After all, its price is high, and its cartridges are very expensive (count 65€ for a box of 20 at the time of writing). In short: coming to the range with a .50 AE is sure to impress everyone!

And yet, the usefulness of this weapon at the shooting range is quite relative… But it offers the pleasure of owning an iconic weapon of the cinema, thrills and excellent memories. The icing on the cake: the weapon is indeed pleasantly accurate.

Shooting

40 rounds, not one more. Let’s write it right away: shooting the Desert Eagle in .50 AE is expensive and tires quickly. The pistol weighs 1,970 kg empty and is very large in size. From our point of view, the ergonomic problem comes from the placement of the two thumbs on the left side of the “slide”: we don’t really know how to position them. Instinctively, it seems unnatural to position one’s thumbs on the slide because of the violent recoil and the fear of losing one’s fingers (Pic. 18). However, if they are placed lower on the frame, the thumb of the left hand naturally comes on the unlocking button of the disassembly key, and the thumb of the right hand comes on the bolt-stop. In both cases, accidentally pressing one or the other can cause a malfunction. Apart from this grip where you have to adapt given the size of the pistol, the rest of the weapon did not pose us any problem. The magazine is very easy to remove and insert. Ambidextrous safety is very easy to handle. The slide does not offer much resistance when pulled backwards, despite four recoil springs. The sights are simple, square and quick to adjust to.

The results at about twenty meters on a 50 pistol target seemed to us to be consistent with what is said about the Desert Eagle. Apart from 2 rather low shots, you could say that the pistol holds the 9 of the target. From our point of view, the main problems are the holding of the weapon and the management of the recoil. We will have to tame the apprehension of the strong recoil to obtain something acceptable on target. Another rather negative point: the trigger weight is heavy (at least 4kg on our example) and itchy. Let’s just say that for the first time with such a powerful weapon, it’s okay (and we don’t claim to be an Olympic shooter either!). On the slow-motion videos, the pistol seems to be rolling in a kind of way: it’s the effect of the bullet forcing on the polygonal bore of the barrel. At the time of the shot, the shooter does not have time to notice it. All he can see is a big ball of fire in front of him and the gun going up strongly. As for the recoil, if it is strong, it remains largely controllable and even when experiencing free-arm shooting. It seems unlikely (for a shooter with even a little experience) to get hit in the face with the pistol, as we saw on YouTube! However yes, the weapon hits in the palm of the hand, and that’s where it tires very quickly, especially if the weapon is not properly gripped.

The Desert Eagle deserves an improved trigger (but in line with its exceptional mechanical characteristics), good ammo and… big hands! The gong shooting proved to be just as fun with good results. Out of 40 cartridges, we noted only one firing incident: the slide did not stay behind during the last firing of one of the magazines. However, this may be related to the incorrect positioning of the thumb. Everything else happened without incident.

Unfortunately for shooters, it seems that only Hornady offers cartridges (to date) on the market (Pic. 19). In addition, these are XTP (eXtreme Terminal Performance) bullets which, according to the manufacturer, are rather intended for hunting, law enforcement (could there be a correlation between the two activities?), and home defense (for countries where it is allowed), but not really for sport shooting. There remains the option of reloading… with projectiles that are also very expensive.

Last point: the springs must be changed, according to the manufacturer owner, Kahr Group, every 1000 rounds (or about every 2500-3000 rounds according to various sites… but let’s trust the manufacturer owner!). While this replacement threshold may seem objectively low, it is related to the nature of the weapon. Moreover, replacing the recuperative springs periodically to extend the life of a weapon and ensure its proper functioning is not exceptional… and should be applied to most weapons!

Operation

The operation of the weapon is like the rest: out of the ordinary. Where the majority of semi-automatic pistols use straight blowback systems (“weak” caliber) or short-recoil of the barrel operation, the Desert Eagle directly inherits its operation from much more powerful weapons: assault rifles and machine guns! Yes, the weapon is gas-operated with a strong 3-lug bolt. While this is not unprecedented (one thinks of the 1973 Widley pistol), it is rare enough to be highlighted.

The design of its gas system is logically adapted to the specificities of the weapon and its caliber but gives a rather unusual result. The gas is taken immediately at the exit of the chamber and then transported to the piston of the bolt carrier located at the front of the weapon by a pipe machined into the lower part of the barrel (this is clearly visible on the patent linked here – Pic. 20). The thing is quite rational: positioning the gas-port further in the barrel would pose two problems:

- On this type of caliber, designed for “short” barrels (by opposition to caliber dedicated to long arms), the pressure drops quickly. Also, a more distant gas-port would therefore be synonymous with a loss of power for cycling.

- The distance between the port and the muzzle of the barrel must remain significant to prevent the time of action on the piston from being too short.

We can wonder here about the “categorization” of this type of gas-system: by “direct impingement” or by “long stroke piston”? Well, if at first glance, you might think “a bit of both”, in the end, the implications are closer to a “long stroke piston”: it’s simply a very, very long pipe between the port and the gas block (i.e. where the piston awaits for gases). Funny detail, the thing can be found on… an Israeli assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More! And yes, the Tavor family (TAR-21, X-95) uses a similar gas-system: a pipe conducts the gas to a piston (a real one, like on the Desert Eagle) attached to the bolt carrier (Pic. 21). In the case of the Tavor family, it is likely that the choice was dictated by the desire to maintain common parts between weapons of different barrel lengths.

The lock is therefore rotary. If the bolt is a little bit reminiscent of the AR-15’s, it has “only” 3 lugs on its periphery and not 7 (Pics. 22 and 23). In our opinion, unlike the AR-15’s lugs, the Desert Eagle’s lugs are quite well distributed. This distribution frees itself from the instinctive (and especially productive) regularity at 120° so as not to implant two lugs too close to the extractor’s groove. As a result, the lug located on the top of the bolt is moved to the right in order to move away from the extractor. A similar reflection would have prevented the AR-15 family’s weapons from suffering from a more than problematic structural fragility: two lugs are literally implanted at the edge of the extractor’s groove. Like a house built on the edge of a cliff, the adventure always ends badly… We will have to wait for the arrival of the G36 to have a solid bolt, with “only” 6 lugs, but well implanted… and much more solid. The number does not count…only total locking surfaces and implantation does.

Without having any proof, it seems quite likely that the designers of the Desert Eagle were aware of the structural fragility of the AR-15. Be careful, the weapon is not without weaknesses. On the Mark I version: we have already seen a piston housing, on the bolt carrier, break. It should be noted that on the following generations, this part of the weapon has been modified: from now on, it seems that it is rather the piston that breaks (rarely) and not the bolt carrier… which is much less of a problem!

Another difference with the Armalite assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More is that the bolt guide pin is not attached to the bolt at the time of firing, but to the bolt carrier. Thus, the cam path is machined on the bolt itself.

The extractor is of the “jumping” type, and the ejector is “spring loaded”, i.e., moved by a spring. This last arrangement, which is also found on many assault rifles, is very clearly a production facility and an economic advantage. The implantation of a fixed ejector with a weapon equipped with a rotating bolt would have been much more problematic. Is this a concern? Not really, especially on a weapon which, as mentioned above, has no operational vocation… other than Hollywood!

The trigger mechanism is somewhat of a stain in the picture: it is fired by a hammer in “simple action” mode reduced to its most “simple” expression… but would anything else have been needed? From a practical point of view, no… but it would have been extravagant to have a double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More with a few automatic safeties authorizing a “chambered weapon” carrying. An extravagance that should be a normality for the Desert Eagle. But all this would undoubtedly be done at the cost of complexity and additional cost… for not so much in the end. So, the thing is rational.

In terms of automatic safety, it should be mentioned that the firing pin, of the “hit and throw“ type, is attached to the bolt carrier and not to the bolt itself: there is therefore no risk of a shot being fired with an unlocked bolt. If the fact that the firing pin is attached to the bolt carrier is directly a legacy of the rotary-lock system encountered on AR-15 type assault rifles (a good point for this mediocre weapon…), the use of the “hit and throw” firing pin is typically inherited from the nature of the weapon… It’s a handgun!

Disassembly

The disassembling of the weapon is “original” because it uses recipes already used on other successful weapons. Thus, the disassembly of the barrel, which after the removal of the magazine and the securing of the weapon will constitute the first step of the disassembly, is reminiscent of that of the Beretta 92: there is a disassembly key on the right side of the weapon, which can be tilted when the locking button, present on the left side, is pressed.

Once the barrel is unlocked, it is pulled slightly forward, which allows it to be extracted towards the top of the weapon. Once the barrel is removed, the bolt carrier group is pushed towards the front of the weapon. Then, one can remove the recoil springs assembly. Depending on the version, the removal of the recoil springs assembly will release (Mark VII and XIX) or not (Mark I) the piston from the bolt carrier. All this constitutes the field disassembling according to the manufacturer (Pic. 24). However, two additional disassembly seems necessary for a good maintenance of the weapon: the bolt carrier group and the magazine.

To disassemble the bolt carrier group, there is a protocol, sharing elements of the Colt 1911… and the AR-15! Indeed, the firing pin plate will be removed, as on a Colt 1911, by pushing the firing pin into the bolt carrier to release the plate, then sliding it downwards. Be careful, once the plate is removed, the firing pin driven by its spring strongly wants to jump out of the weapon. Once the firing pin and its spring have been removed, the bolt guide pin is removed: to do this, it is necessary to compress the bolt stabilizer in order to have the bolt enter a little bit inside its carrier. Once the bolt is positioned, the bolt guide pin can be removed from its housing using the tool present in the collective unit. Once the bolt guide pin has been removed, the bolt and its stabilizer, spring and guide rod can then be extracted. As mentioned, this protocol will not be totally alien to people used to the AR-15 (Pic. 25).

Finally, the disassembly of the magazine, which is very classic. Thus, the magazine base locking plate is pushed back through a hole in the magazine and then the base is slided forward. Here too, remember to oppose the thumb to the sudden decompression of the magazine spring. Once the magazine base is removed, the locking plate, the spring, and the follower are extracted.

Conclusion

A pure and hard fruit of the American civilian market in the 1980s, the Desert Eagle has been able, despite its questionable usefulness, to rise to the rank of legendary weapon. Better still, it is a symbol: that of the action cinema of the 1980s and 1990s. Also, it reminds us that in our consumerist societies (and we are all actors in it), the simple evocative power of an object can compensate for its total lack of rationality… So, if you have the means and if you really want to go for it, go for it. You won’t be disappointed, and we don’t know of any Desert Eagle owner who has let go of his beast with a happy heart… on the sine qua non condition that you don’t use it for a purpose it was not designed for!

Thomas Anderson & Arnaud Lamothe

- Obviously… it’s a joke! But we are curious to see if this fable, which is not serious, will be taken up by some…

Special dedication to Ronan Le Douaron.

Sources:

Patent N°4563937 of 1983:

https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/63/20/12/1a0b13733190c9/US4563937.pdf

Patent N°4619184 of 1985:

https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/37/06/96/f2319824f41e45/US4619184.pdf

Advertising of the L6 model:

https://www.magnumresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/DE50L6IMB-Retail24.pdf

Page on the history of the weapon on the manufacturer’s website:

https://www.magnumresearch.com/company-history/ #

History of the .50AE cartridge:

https://forum.cartridgecollectors.org/t/50-ae-experimental/12474