If the Soviets were prolific in terms of armament, the pocket pistol was for a long time a poor cousin, especially represented by the pistol “Tula-Korvin” or TK-26 in 6.35×17 SR. It had been designed back in 1926 and its production had stopped by the mid-1930s.

Teamwork

Officially adopted in 1972, the Pistolet Samozaryadniy Malogabaritniy (small-size semi-automatic pistol) abbreviated PSM was developed in Tula, one of the most important places of Russian and Soviet armament. The team in charge of the project was composed of Tikhon Ivanovich Lashnev, Anatoliy Alexeevich Simarin and Lev Leonidovich Kulikov. These three designers were well established and well-known for their competence. T.I. Lashnev had worked with Fedor Tokarev and Sergey Korovin before working after the war on hunting weapons and sport shooting. A.A. Simarin had worked in Tula on industrial equipment such as a pneumatic pistol (the first in the USSR) and ammunition design for an industrial pistol. The team could count on the help of E.F. Moiseev, researcher and engineer in Tula. The group emulsion was excellent and quickly resulted in a weapon that perfectly met the criteria, to the point that it was quickly put into production after a series of successful tests. This production took place in Ishevsk and not in Tula, the industrial necessities probably taking precedence over any other form of consideration. The specifications of the weapon insisted in particular on a reduced weight and dimensions, dimensions “similar to a matchbox” to use the words of A.A. Simarin, but also on the reliability of the weapon which had to be in line with a military use. Concurrently with this working group, a team was given the difficult task of adapting the Makarov Pistol (describe in the previous chapter) to the 5.45×18 cartridge. This type of mission is complex, especially when the differences between the calibers are so significant: a weapon is designed around a caliber and a given ammunition. This attempt was a failure nonetheless the approach is still interesting: had it been successful, it could have further simplified the productive, logistical and training problems.

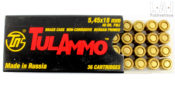

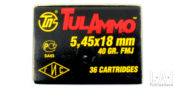

The 5.45×18 ammunition

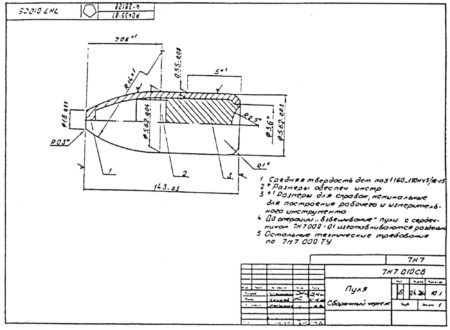

This small munition has a total weight of less than 5 g for a bullet weight between 2,4 and 2,6 g. Its bottleneck rimless case welcomes 0.15g of powder. The final design of the service ammunition would be finalized by Aleksandr I. Bochin in 1979, almost 7 years after the official adoption of the weapon! The Russian-Soviet author D.N. BOLOTIN attributes to the 5.45×18 ammunition an efficiency close to the 9×18 Makarov ammunition. This deserves some explanation. The terminal effectiveness of a small arms ammunition for military use can be broadly defined by two criteria: perforation and lethal capacity. The service ammunition, called 7-N-7 within the Soviet system, has a flatted cylindro-ogival bullet with a flat base. As is often the case in Soviet small-caliber ammunition, the bullet core consists of a lead part and a mild steel part, the whole being jacketed with tombac-plated steel. Here, the two parts of the core are superimposed: steel at the front, lead at the back. Even if its perforation contribution depends on the materials hit, the presence of a steel core has in any case the advantage of increasing the probability of the presence of a residual bullet fragment of significant size after passing through a first layer. In the case of lead core, it is not uncommon for the bullet to be completely disaggregated by the impact in some materials, generating a cloud of metal fragment with a more limited lethal capacity. We must not make a generalization here: terminal ballistics has too many variables for this. Another advantage of using steel in bullets (such as in cases) is economical: it saves lead and copper, especially on very large-scale productions. The qualification of this type of bullet as “armour-piercing ammunition” remains a question of point of view, semantics or legislation: from a personal point of view, it is an “ordinary ammunition” for this caliber. Like the ammunition 7-N-6 and 7-N-10 of 5.45×39, the front part of the bullet has a vacuum. The whole of this construction allows a far rear location of the center of mass of the bullet, thus favoring the tilting of the bullet on impact in a soft material, but also better performance in terms of external ballistics. When tilting, the bullet exposes its flank, 14.20 to 14.50 mm long to the target and promotes a rapid transmission of energy by moving matter. For comparison, the bullet is longer than that of the 9×18 M, which measures 12.51mm. It is likely that this tilting takes place only a few centimeters after penetration into a soft body, as does the 7-N-6 ammunition of 5.45×39 which is contemporary to it. Regarding perforation, in addition to the composition of the bullet, the speed and the sectional densityThe sectional density is the division of the weight of the b... More of the bullet constitute two important factors in equation. Here, we note that the speeds in 9×18 M and 5.45×18 are comparable (close to 315 ms-1) and that the sectional densityThe sectional density is the division of the weight of the b... More of the 5.45×18 is higher than that of the 9×18 M. The performance in terms of perforation is therefore logically higher than that of the 9×18 Makarov. The literature on the subject commonly states that the 5.45×18 ammunition fired in the PSM would be able to pierce 30 to 45 Kevlar layers with a residual energy still lethal at usual distances of use (that is, in the case of a handgun, between 0 and 15 m). Beyond the announcement effects, it is a question of keeping our head on our shoulders: it is an ammunition for a handgun intended for personal defense and not an assault weapon. The effectiveness of this ammunition should not be compared to anything other than a handgun ammunition intended for the same use. In this case, the comparison with the 7.65×17 SR or the 6.35×15 SR gives the advantage to the 5.45×18, while presenting interesting capabilities compared to the 9×18 Makarov. The same thinking applies to the caliber from the “Personal Defense Weapon” program that are the 4.6×30 and the 5.7×28. It would be illusory to want to substitute assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More calibers by these calibers because the hit probability with the weapons dedicated to them, lighter and more compact than an assault rifleAn assault rifle is a weapon defined by the use of an "inter... More, is excellent in the 0-200 m section. Back to the PSM, the low energy of the ammunition has another undeniable advantage: on a straight blowback weapon, it allows a considerable lightening of the bolt (here the slide), and therefore of the weapon. Remember here that the straight blowback weapon operation mainly relies on the weight of the bolt: its weight opposing the recoil of the case in the chamber. Thus, the more powerful the ammunition, the greater the weight must be. Another advantage lies in the size of the complete ammunition: despite a reduced size, the magazine capacity still has 8 rounds.

Annual subscription.

€45.00 per Year.

45 € (37.5 € excluding tax) Or 3,75€ per month tax included

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!

Monthly subscription

€4.50 per Month.

4.50 € (3.75 € excluding tax)

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!