PPS-43, Aleksey Sudaev’s masterpiece

When Soviet forces entered WWII, the submachine gunSubMachine Gun More was one of their arsenal’s weak points. Available in insufficient quantities, the USSR had to considerably increase its production capacity. The adoption of a simpler production weapon was a major response to this problem.

The situation in 1941

At the time of the German offensive known as “Operation Barbarossa”, the Soviet Union had mainly two models of submachine gunSubMachine Gun More (Pistolét-Pulemyót in Russian or PP for short) of national design in its arsenal: the Degtyarev model 1940 or PPD-40 and the legendary Shpagin model 1941 or PPSh-41, or “Papasha” for those who are intimate enough with the weapon (article about the PPSh-41 here – Pics. 04 and 05). Both weapons used the powerful ammunition of the Tokarev TT-33, the 7.62×25 itself derived from the 7.63 Mauser of the C-96 pistol. The PPD-40, with a more complex industrial design than the PPSh-41, was to make way for the latter. The PPSh-41, meanwhile, met many of the requirements of the Red Army, but still had a big flaw: its availability! The weapon was indeed very little available, something very problematic in a modern war that was the “Great Patriotic War” of its time. At a time when the bolt-action rifle occupied most of the arsenals, there was no need to insist on the tactical advantages of a short weapon, with a high capacity and allowing automatic firing. It should be highlighted here that the concept of “high capacity” is to be contextualized: in the aftermath of the First World War, a 32-round magazine for an individual weapon already constituted a revolution.

If one can spontaneously think that it’s only needed to build factories to increase production abilities, this solution is neither necessarily easy nor optimal. The creation of a production line is an expensive operation, especially if the weapon to produce is not very successful on a production level (consumption of raw material and production time). From then on, in a difficult context linked to German advances, the Soviets launched in early 1942 a competition between several of their designers for the realization of a new SMGSubMachine Gun More. The competitor should consider precise production concepts but also operational requirements. At the production level, designers had to accommodate the following requirements: manufacturing technology limiting the need for machining, minimizing the waste of raw materials, using low-alloy steel, all that for a reduced production time. Operational requirements included reduced dimensions and weights to encourage the use by vehicle crews and specialized units, as well as a lower rate of fire compared to the PPSh-41 to increase the accuracy of burst fire on a lighter weapon. Gunsmiths that were on the line Vasiliy Degtyarev, Georgiy Shpagin, Aleksey Sudaev, Sergey Korovin and Nikolay Rukavishnikov. Suffice to say for the enlightened amateur of Soviet weapons, nothing but the bests of that time. An evaluation of the prototypes was conducted from February 25th to March 5th, 1942, except for Shpagin’s weapon, the PPSh-2 which was evaluated from May 30th to June 2nd, 1942. Although the weapons were not without qualities, it was decided to send the designers back to their boards in order to perfect their prototypes. Let us specify here that in the case of the Soviet Union, comparisons with invitation to tenders to Western standards would be meaningless: here, designers were encouraged to produce the best possible weapon, even if it meant taking the ideas of the comrade! Only the result counted. A new evaluation took place from July 9th to 13th, 1942. In the end, the Sudaev weapon was selected. In parallel with the development of these SMGs, a sergeant wounded in action in his tank was developing his own SMGSubMachine Gun More during his convalescence: his name was M.T. Kalashnikov. Having understood the importance of this type of weapon and its deficiency in the Soviet ranks, he had undertaken to create a weapon to fill this gap. The weapon was examined by the authorities but not selected. It was too complex and, no doubt, far from productional consideration of which Kalashnikov was probably not completely aware. However, the creativity of the individual would be recognized and his talent in the material put to good use! The rest is History.

From adoption to production

The weapon produced, initially under the name “Pistolét-Pulemyót Sudayeva” 1942 or PPS-42 met the expectations of the Soviets. Compared to the PPSh-41, it is lighter by nearly 500 grams with an equivalent capacity, more compact with its folding stock, considerably reducing production problems (the division of consumption of raw material and working time are greater than 2). The weapon is reliable, accurate, and simple to operate. Its rate of fire is reduced compared to the PPSh-41: announced at 1000 rounds per minute for Shpagin’s weapon, and at 600 for Sudaev’s. Our personal measurements on a shooting session are however different: 1081 rpm for the PPSh-41 and 804 rpm for the PPS-43… beware of the announced data! Wasting no time, Sudaev was sent to Leningrad (now and formerly Saint Petersburg) to oversee the production of the weapon. The weapons produced were thus directly deployed on the front, the city experiencing one of the most brutal sieges of the war. The production would be carried out, among other things, on machines from the nearby Sestroryetsk factory, which was moved to the city in a hurry in front of the advance of the Axis troops. During the siege, Sudaev not only supervised the production, but also worked to perfect his work, an approach similar to that carried out by Kalashnikov throughout his career. Thus, he would correct the defects reported on it and even incorporate elements of a SMGSubMachine Gun More designed by I.K. Bezruchko-Vysotsky. All the modifications made on the weapon would result in a new model called for its adoption PPS-43. From then on, this weapon would be mass-produced from the beginning of 1943 in several factories that were generally not accustomed to the production of the weapon. As a paradox, the Soviet authorities decided not to substitute the production of the PPSh-41 for that of the PPS-43! The factories, which had been moved and reorganized due to the German progression, were already configured for Shpagin’s weapon production and also had significantly increased their productivity. Also, the PPSh-41, although not devoid of flaws, enjoyed great popularity among the troops of the Red Army. This was also the case of the PPS-43, whose popularity would cross borders, the weapon received a warm welcome from (just like the PPSh-41) the Germans (MP-719(r) in their nomenclature), but also produced by other countries after the war including: Finland (m/44 in 9×19), Spain (DUX 53 and 59 in 9×19), China (Type-54) and Poland (wz.43/52). All these countries would produce variants of the PPS-43. Nazi Germany reportedly even considered producing a copy of the weapon under the name MP-709. It would not have been the first time that Nazi Germany had engaged in such a process…

Mechanical autopsy of a success

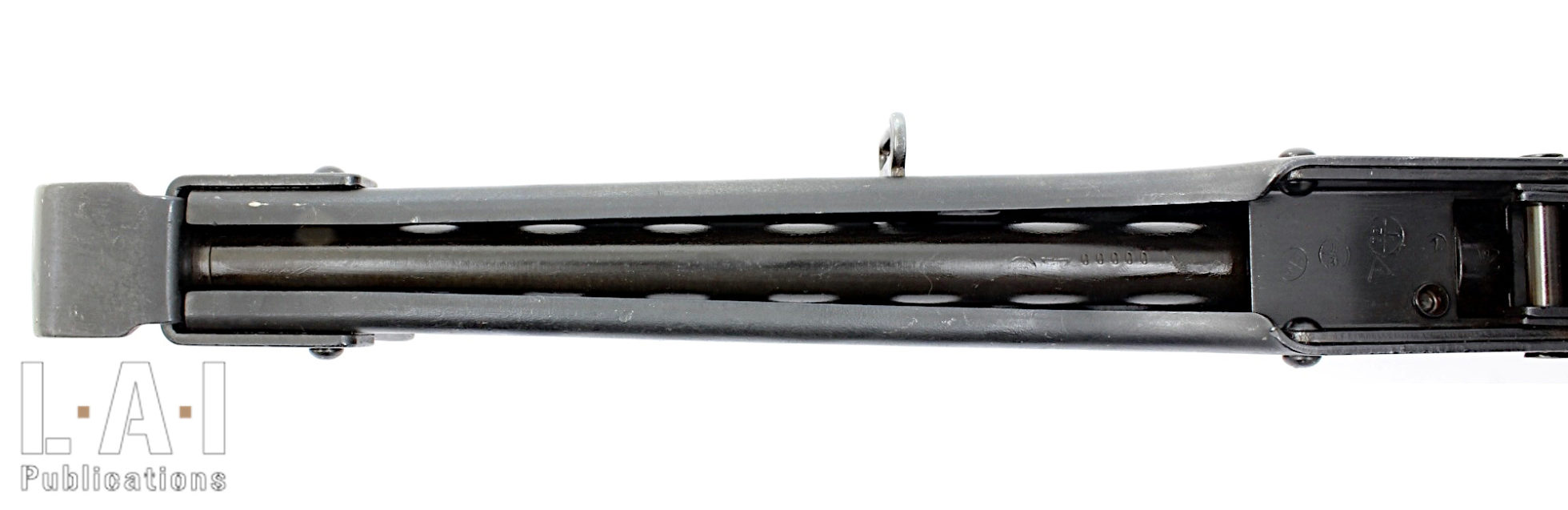

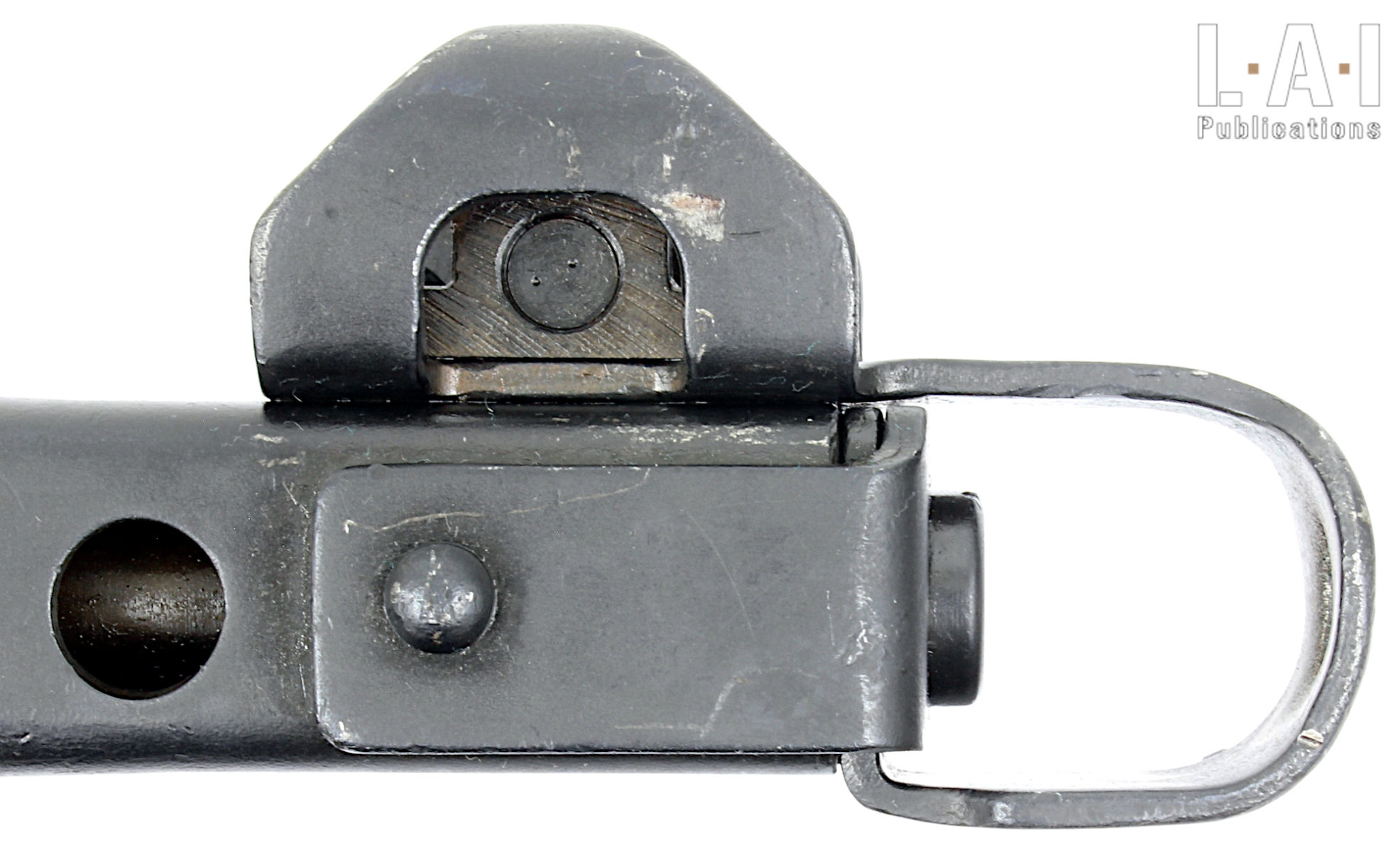

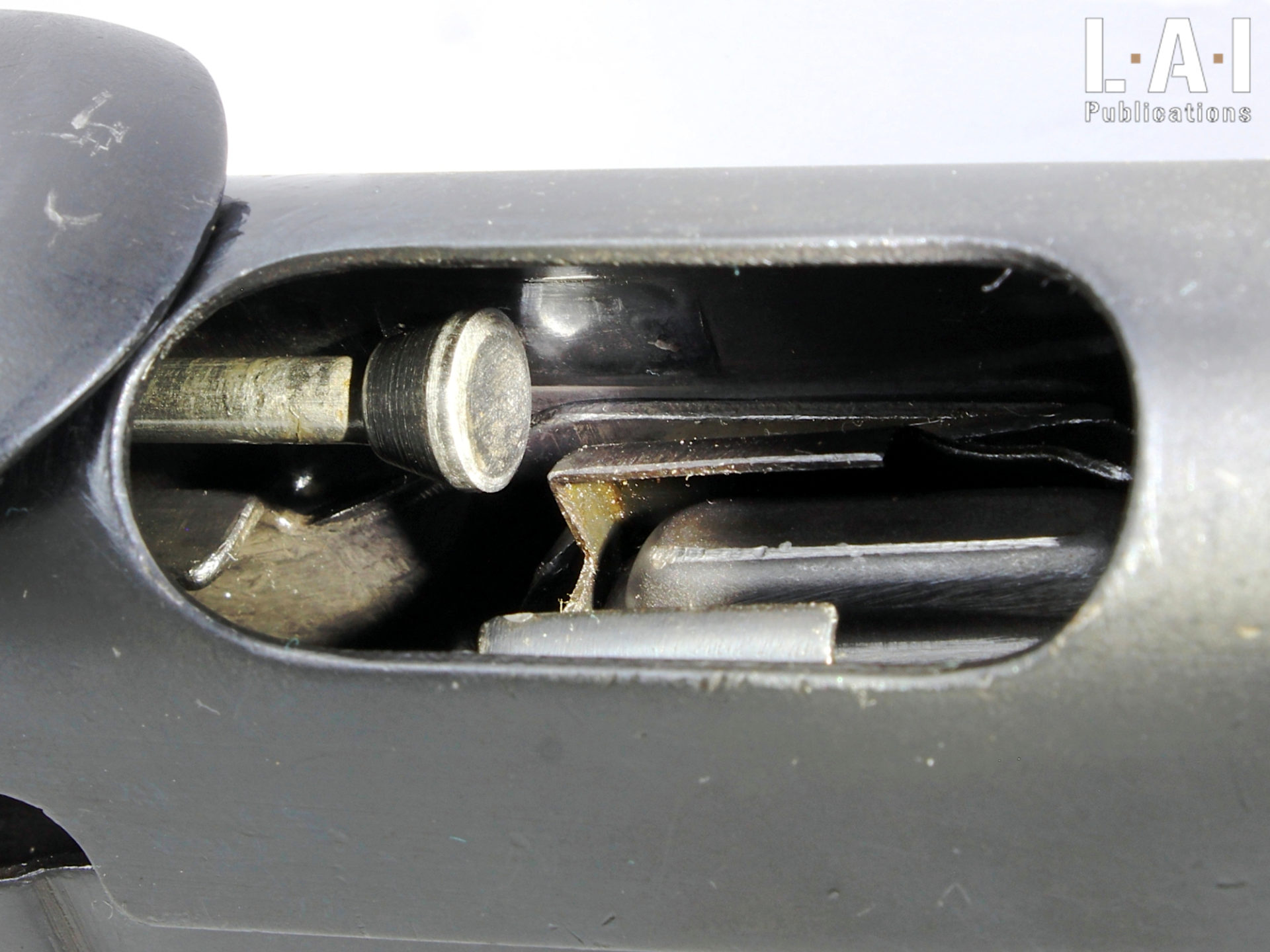

The design of the weapon makes massive use of stamped sheet steel, spot welding and riveting. The frame of the weapon consists of the assembly of an upper and lower receiver of U-shaped sections, articulated around a pivot pin located at the front of the lower part. This articulation, which is familiar to us on many contemporary weapons, was already commonly used since the first productions of SMGSubMachine Gun More. The upper receiver covers the barrel for its entire length in order to prevent hand contact with a burning barrel (you can find a fun fact about hot barrel at the end of this article). The lower part of this protection is open and has many circular openings on the rest of its periphery, thus promoting the cooling of the barrel (Pic.06). The barrel muzzle is completed by a device combining muzzle brake and climbing compensator (Pics.07 and 08). Made of stamped steel, it also protects the barrel’s mouth from shock and from the introduction of foreign bodies (mud, snow, etc.). The lower receiver accommodates a stamped steel magazine well, also officiating as a front grip, a welcome evolution of the ergonomics of the weapon compared to the PPSh-41 where the off-hand does not instinctively find a position besides on the magazine. The magazine latch is housed at the back of it within a fairing that guarantees both its protection and promotes its accessibility (Pic.09). There are few machined parts: even the trigger, the sear and the magazine latch are made of stamped steel. Parts with multiple functions are honored: the guiding rod of the recoil spring also acts as an ejector (an evolution compared to the PPS-42, probably from the SMGSubMachine Gun More of Bezruchko-Vysotsky), the trigger spring also acts on the sear and assembly lock of the weapon (Pic.10). Simplicity prevails, for example, the slowdown of cyclic rate is achieved by an extension of the travel of the bolt. It therefore takes longer to complete its cycle. At the end of the course, the bolt meets a leather or synthetic buffer (depending on the production) allocating a better service lifetime to the weapon. A similar buffer existed on the PPSh-41 and had caused problems for the Soviets regarding its supply. Here, this longer course of the bolt makes it possible to reduce the impact when the bolt meets the buffer and therefore allows a lighter device than on its predecessor. The barrel is simply pressed and pined inside the upper receiver. The stock, also made of stamped steel, folds on top, in a fashion that is clearly of German inspiration (MP-38 and MP-40). Keep in mind that it is the first folding stock of the Soviet army and that the MP-38 inaugurates this practice that – as far as we know – is still in vogue today. Its implementation is done by the action of the locking stock pusher, protruding on the upper and rear part of the upper receiver (Pic.11). Some foreign productions would adopt a fixed wooden stock, probably much more comfortable when the weapon is fired. The pistol grip is lined with a pair of synthetic grips. On the PPS-42 they were made of wood.

The magazine is double-stack and double-feed: the ammunition is presented in turn on the right lip and then on the left lip (Pic.12 and 13). Equipped with a curvature adapted to the ammunition, its filling is easy without even the help of a loader. Anyone who has loaded the magazine of a Sten, MP-40 or even MAT-49 will understand the advantage of this. In addition, this magazine though with little roughness, fits more easily in magazine pouches than did the 35-shots magazines for PPSh-41. The transition to the PPS-43 also marked the end of the use of the drum magazine, mythical certainly, but less practical, less reliable, and more expensive. Some more recent feedback from the weapon, still encountered sporadically in the field and particularly in Africa, has shown us that this magazine would still suffer from a relative fragility, certainly, nearly 50 years after their manufacture. The information seems very interesting to us, especially because it does not come from the Soviet arcana. It also seems to us to be relevant in the light of the schemes that would subsequently be adopted for the magazines made of sheet metal produced for the weapons that would follow in the USSR: the lips of the magazines would therefore be strengthened.

Operation

Firing is carried out from an open bolt: the action of the trigger releases the bolt which takes an ammunition from the magazine and hits its primer at closing. The firing pin is permanently protruding from the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More. The firing pin is a spare part that is hold in place by the extractor, a plus for production and maintenance (Fig.14). Open bolt shooting has the advantage of considerably simplifying the weapon by freeing it from a more complex trigger mechanism but also of interrupting the firing on an open bolt. It thus favors the cooling of the barrel and eliminate the thermal auto-ignition of the ammunition from a very hot barrel qualified as “cook-off”. The major disadvantage is the possibility of the intrusion of foreign bodies into the weapon between the shots. Some weapons adopt automatic shutter systems to overcome this problem, but this is not the case here. The weapon operates from a simple blow-back principle: when the round is fired, the difference in mass between the bullet and the bolt is sufficient to give the bullet the time necessary to leave the barrel before the bolt (and therefore the case base) operates a critical recoil. The rest of the rearmament is done on the inertia thus stored. We are given here the opportunity to return to a theory in vogue, initiated to our knowledge by the American author Anthony G. Williams. The latter claims that weapons operating on the open bolt / blow-back would benefit from a phenomenon qualified by the Anglo-Saxons as “Advanced Primer Ignition” or “API”. The idea is that the ammunition would be fired while the bolt would still be moving forward and that, therefore, the bolt would benefit from the inertia of its movement to “counter” the shot. If the weapons operating with the principle of the API do exist (in particular the German Mk108 gun in 30mm), they reside on the principle of firing before the total chambering of the ammunition. Thus, bolt, chamber and in the case of the Mk108, even the ammunition, are designed to be fired with a munition whose body is fully supported by the chamber without being completely chambered. The bolt will even telescope inside the chamber for a significant distance after firing. The extractor then plays a major role in the percussion: it keeps the ammunition in the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More. Nothing like this here: to be fired, the cartridge must be fully chambered so that the firing pin can hit the primer with strength. On its forward movement, the inertia of the bolt is used several times: taking the ammunition in the magazine, introduction into the chamber, passage of the extractor on the case base, then firing the primer. It is the front movement of the bolt that ignites, at the end of the course, the primer. It should be noted that there is a period of time between the moment when the primer is struck and the moment when the powder charge ignites, but during this period of time, the bolt is already halted. Additional factor, the weapon is not rigidly (in the physical sense) fixed by the hands of the shooter. So, when the bolt is stopped, the inertia of its movement is partially transmitted to the weapon. Put end-to-end, it is unlikely that the bolt, then stopped against the case, still benefits from its inertia of movement when the shot is starting. Worse still, it is not completely excluded that in the event of contact with a metal surface (receiver or rear of the barrel) it may not have started a phenomenon of “elastic rebound”. This is the phenomenon that bounces a hammer when it is hit on a hard surface such as an anvil. In the end, from our point of view, the quantifiable exploitation of the API principle on this type of weapon seems to us highly unlikely. Everyone will make up their own mind.

The torque of simple blow-back / open bolt fire is rigorously classic for weapons of this category and for this period, although there are exceptions.

A classic operation

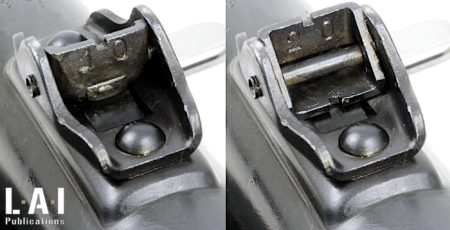

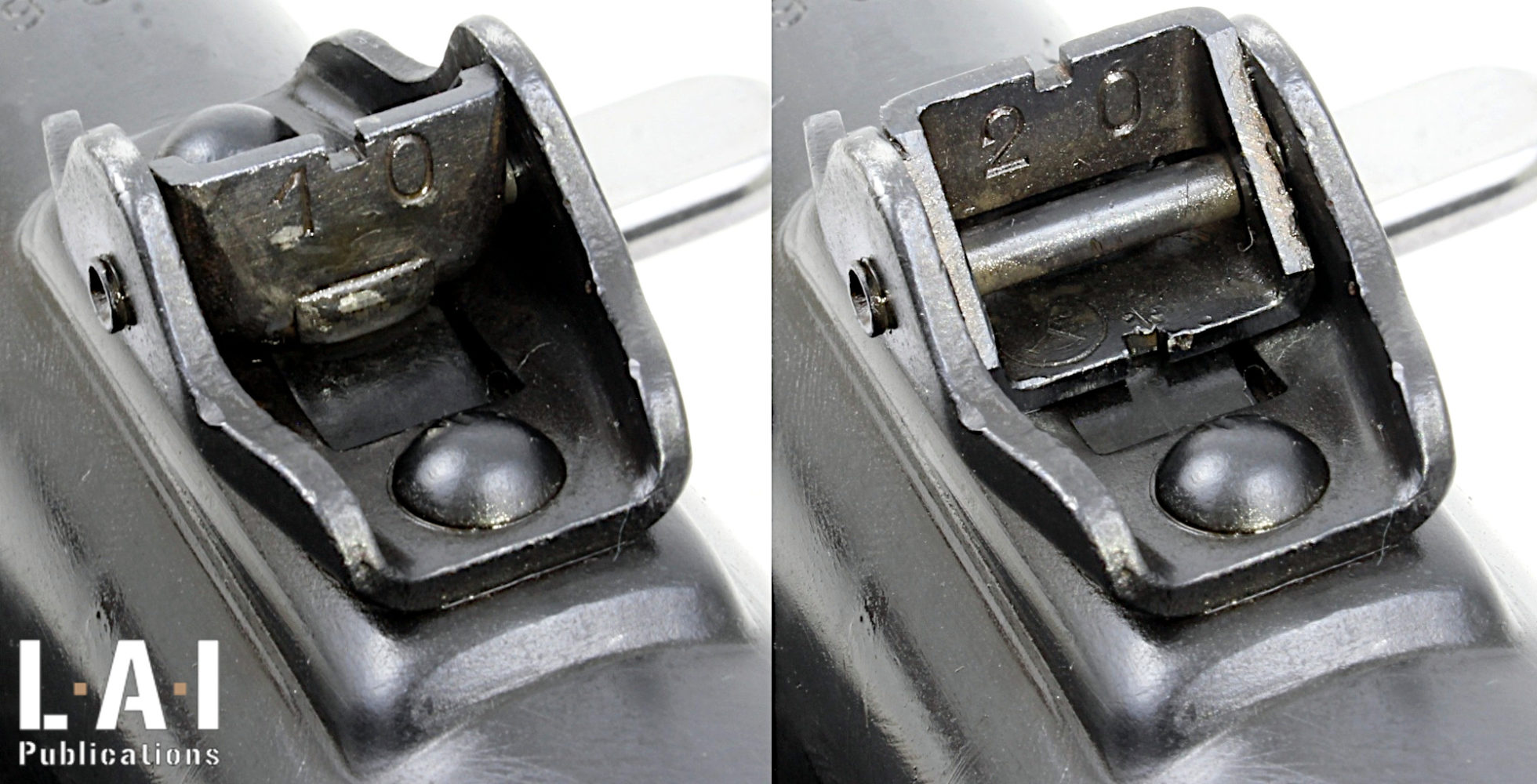

The cocking handle is attached to the bolt on the right side. The safety consists of a sliding lever located at the front right of the trigger guard (Pic.15). When it is off the trigger guard, the weapon is ready to fire and when it protrudes inside, the weapon is safe. Safety engaged, the squeezing of the trigger is impossible, and the travel of the bolt is restricted, even when it is in the front position. Safety on, it is therefore impossible to handle a bolt in the closed position, even partially, which can lead to accidental hit departures on some weapons. It should also be noted here that if safety is not engaged, a partial armament of the bolt can lead to the departure of a blow without action of the trigger. Indeed, the bolt travel necessary to catch the sear is much higher than the threshold where the bolt crosses the magazine. This would undoubtedly constitute, by current standards, a fatal defect in the commissioning of the weapon. The only firing mode is automatic. To produce a single shot, you must therefore learn to manage the trigger release. The thing is actually rather simple and therefore does not constitute a real defect, especially since this choice allows a significant simplification of design and production. The sight consists of a L-type flipped rear sight and a front sight post (Pics. 16 and 07). The rear sight has two flipping positions marked 10 and 20, in decameter, or 100 and 200 meters. The post is adjustable in both elevation and direction, which allows to refine the adjustment of the weapon. While this provision is often absent from SMGs during this period, it should be noted that it was already present on PPSh-41. The device is of the same type as on SKS-45 or AK: the direction adjustment is done by moving the post support by sliding by means of a dedicated tool, and the elevation adjustment by screwing / unscrewing the post with a tool similar to that of the aforementioned weapons. The front sight is protected by larges stamped steel ears (Pic.07).

Disassembly

After clearing the weapon, it is necessary to return the bolt to the front position. This oversight will be cruelly punished: the disassembling consisting in uncoupling the lower receiver (hosting the sear) and the upper receiver (hosting the bolt), this will lead to the releasing of the bolt. Worse still, if this operation is carried out with a loading magazine engaged, the possibility of a shot is not excluded! Other times, other uses. Here too, this point would probably be prohibitive to the commissioning of the weapon today. The weapon cleared and bolt at the front position, one can tilt the lower receiver of the weapon by the action of the cursor located on its rear end (Pic.17). The same spring is here used to provide three different functionalities: trigger and sear return as well as cursor return. The rear end of its guiding rod ensures the locking of the two receivers. Note that it is not possible to activate the trigger if the cursor is not back in position and therefore locked. A good point at the security level that cannot overshadow the criticisms made previously. The axis constituting the hinge between the two receivers being crimped, it is not possible to separate the two receivers. Lower receiver tilted, the bolt and its recoil spring assembly can be removed by a short moving back of the bolt and then by taking it out of the receiver. The recoil spring assembly is then detached from the bolt simply by sliding it on its left side. This disassembly will be completed by that of the magazine: after pushing the magazine floor plat lock inside the magazine, the floor plat is slided forward or backward. As soon as it leaves its guide rails, the spring and floor plate lock come out of the magazine, the follower comes next. One will also think during this operation, to oppose his thumb to the parts under tension in order to control the violent decompression of the spring (Pic.18). For the most demanding, this disassembling could be completed by removing the extractor and the firing pin: it is then necessary to push the extractor pusher and its spring into its housing and, simultaneously, to remove the extractor (Pic.14). Once the extractor is removed, you can take out its pusher and spring as well as the firing pin. This operation, facilitated by the taking of the bolt in a vice, is difficult to achieve on the field.

Shooting and cleaning

The weapon is very pleasant to shoot. The muzzle device does its job: if the weapon twitches in the hands, we feel that this is more due to the displacement of the bolt and its stop than to the recoil of the start of the shot. The automatic firing is of course very controllable, but this is the case of most non-compact SMGs that we have tested to date… a good part of the common productions since 1918! I have always been fascinated by the commercial argument that explains that a SMGSubMachine Gun More in 9×19 (or even 7.62×25) of more than 3 kg is controllable in automatic firing: the opposite would be surprising! The stock is less unpleasant to the cheek than one might think, even if its contact is less comfortable than a venerable wooden stock. Targets are easily reached up to 100 m. It is probably possible to reach the targets at 200 m, but the exercise seems to us difficult to reproduce in an operational context, unless we consider the efficiency obtained by a large number of shooters (with a good saturating of the targeted area). Cleaning the weapon is easy, as it has excellent accessibility. It will be important to achieve this quickly after firing, especially if the ammunition used involves a corrosive primer as it is common in ammunition from surpluses in former Warsaw Pact countries. The presence of a chrome-lined barrel on some manufactures (including Soviet) does not exempt from this exercise!

Due to the use of automatic weapon receivers, semi-automatic versions of Pioneer Arms are, in France, considered A-category weapons by the Service Centrale des Armes et Explosifs (SCAE), the French regulation service about firearms and explosives. And even if these productions fire from a closed bolt and by the action of a hammer in semi-automatic only, these remain weapons from the transformation into an automatic weapon. This is a shame because this weapon has, like many others in its category, a really enjoyable potential.

Conclusion

It is said that after the war M.T. Kalashnikov declared that the PPS-43 was the best SMGSubMachine Gun More of the “Great Patriotic War”. If we must be humble in the face of the great man, it would be wise not to be so peremptory. The evaluation of a weapon can be carried out from many angles: production, precision, reliability, safety, ergonomics, finish… To say that one weapon would be the best of all would be to conclude that it surpasses the others in all areas. Clearly, this type of statement is probably only rarely (never?) objectively justified. Let’s bet that Mikhael’s patriotism was no stranger to his words, something to his credit! The weapon remains a total success compared to the Soviet specifications and a remarkable combat weapon. But do not lose sight of your reason, remain critical of both the man and the weapon.

Arnaud Lamothe

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!

Thanks:

ESISTOIRE for the provision of the weapon: Laura, Yann, Laurent and Guillaume, always at the top!

A little real-life anecdote about hot barrel: during a shooting session with a light machine gun, a professional unaccustomed to this kind of weapon undertook to move the LMG after the firing of more than a hundred cartridges … by the barrel! The result was not long in coming and the end of the story took place in the hospital. Food for thoughts.