SKS: The Soviet Marvellous Mistake

The advent of the first intermediate caliber in the Soviet Union, adopted in its first form 7.62×41 mm M43 in 1943, then in its final version 7.62×39 mm M43 in 1945, led to the entry into service of 3 weapons in the aftermath of the WWII. If the AK was perfectly in tune with the times, the RPD was a precursor of the “Squad Automatic Weapon” and the SKS was… objectively already outdated in several aspects at the time of its adoption by the Soviet Army! But this adoption was not without reason, and Simonov’s weapon remains, in any case, marvelous in many respects.

(Because our English translator is actually not available, the following version has been translated and corrected by me, the author, on my own. English is not my native tongue : I apologized here for the mistakes I made.)

A need that has passed?

In the aftermath of the October Revolution and the Russian Civil War, the “Reds” inherited a largely agricultural, poorly industrialized country with a poorly educated population. Regarding education, it is necessary to point out that this state of affairs is much more the result of years of war than of an Imperial policy neglecting the education of its population. Contrary to what some might believe, during the reign of Tsar Nicholas II, a large part of the population had access to schools and the level of education was probably no worse than in other so-called “industrialized” nations at the beginning of the WWI. In any case, the situation was considered “worrying” by the Soviets, as education was strategic in all areas. In order to achieve the coveted position of “modern industrialized nation”, the regime introduced a large number of reforms (with some setbacks that we know) among them, reforms on the education system.

However, it is clear that the effects of such reforms are not felt instantaneously. And in the case of education and the Soviet Union, the matter is probably even more complex to implement because of the immense extent of the territory and the rural nature of its population. At the time of the 1926 census, 82.10% of the population lived in rural areas. For comparison, this percentage was 25.21% in the 2021 census! It is also necessary to point out here that education does not only provide the ability to “read and count”: it also greatly improves the ability to interact and to adapt. However, we will avoid the shorthand of saying that it develops “intelligence” here. The subject is far too complex to make such shortcuts and our modern societies have proven to us many times that it is not because we have attended the most prestigious schools that we cannot show the dirtiest stupidity there is… On the other hand, history is filled with prodigious self-taught people!

In any case, how well educated the population is must be taken into account in all things… and especially in military matters. It is therefore incumbent on the provision of equipment adapted to this population. For the infantryman, if life is not limited to shooting and cleaning his weapon (far from it…), it is nevertheless necessary to have a “simple” weapon at his disposal in all these aspects. The bolt-action rifles of the two world wars perfectly meet this requirement of simplicity: the field disassembling is often limited to the removal and disassembly of the bolt, sometimes accompanied by the removal of the feeding system. However, the technical developments initiated during the interwar period clearly set out the future of infantry armament: the future would be semi-automatic and even automatic! Thus, in order to maintain the “firepower” at the same level while taking into account the nature of the population constituting the troops in the event of mobilization, it is necessary to design an adequate weapon. It was at this crossroads of needs that the SKS was born towards the end of the WWII. The weapon is intended to be simple for easy and effective use by a poorly trained troop. And indeed, the SKS excels in this job: no bursts, no magazine management, no bayonet loss. The weapon is made up of “large” sub-assemblies, which are not very prone to breakage, loss and which are easy to clean. At the beginning of the WWII, there is no doubt that such a weapon would have been a formidable asset on the battlefield.

But therein lies the problem: this weapon was not put into production until 1949, concomitantly with a certain “AK” (the one that is often called AK-47 so as not to be confused with the many other variants of this family of weapons), and while the world was leaving (at least for a while) massive troop commitments in favor of nuclear deterrence. On August 29th of the same year, the first Soviet nuclear bomb “RDS-1” detonated. The end of mobilization in 1945 had melted like snow in the sun the numbers of the Red Army (which had exceeded, at its peak during the war, 34 million individuals) while somewhat “professionalizing” the remaining manpower in a very young “Soviet Army”. Thus, in this context, the SKS simply became one more weapon in an already (too) diversified Soviet arsenal. Moreover, it was a weapon that met a need that no longer existed in the USSR. Indeed, the general level of the military population, which was smaller and better trained, allowed the use of more complex, more versatile and, ultimately, more effective weaponry. It is not surprising, therefore, that pragmatically, the manufacture of the weapon was abandoned as soon as the mid-1950s.

Sergei Gavrilovich Simonov

Spotted in 1918 by V.A. Degtyarev while working on parts of the weapons designed by V.G. Fedorov, Sergei Gavrilovich Simonov was very quickly associated with the design of semi-automatic and automatic rifles and carbines. He presented many prototypes from 1926 onwards and was first recognized with the adoption of the AVS-36 in 1936. According to Soviet author D.N. Bolotin, 65,800 examples of this weapon were produced by the time production stopped in 1940. While the semi-automatic rifles that will succeed the AVS-36 will be F.V. Tokarev’s SVT-38 and SVT-40, this is by no means a sidelining of the designer. On the contrary, it will be put to work for the realization of PTRS-41 (described in detail in the article linked here) in incredible urgency. It is therefore logical that S.G.Simonov will be one of the people asked to develop a semi-automatic carbine for the brand new intermediate caliber adopted in 1943: the 7.62×41 mm. Among the other weapons designers who were called upon were V.A. Degtyarev, N.V. Rukavishnikov, F.V. Tokarev (according to Maxim Popenker), but also, in a very well-documented way, M.T. Kalashnikov, who signed here one of his first official participations in the design of a weapon for the needs of the Red Army.

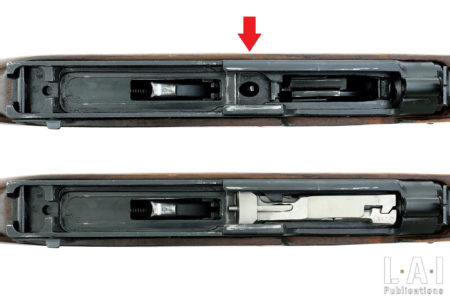

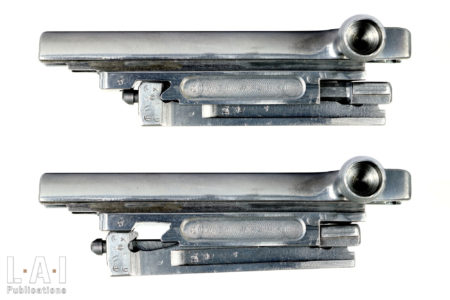

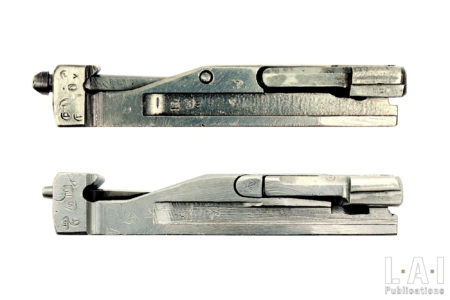

As with the PTRS-41 semi-automatic anti-tank rifle, S.G. Simonov’s work on this new carbine is mainly based on a 1941 semi-automatic 7.62×54 mm R carbine of his own design. It was therefore the opposite of the design of the semi-automatic anti-tank rifle: not an increase in caliber (towards the 14.5×114 mm for the PTRS-41), but a reduction in caliber towards what would eventually become the 7.62×39 mm (Pic.02). This work, which is not strictly speaking “simple”, is nevertheless easier in this sense: the mechanical constraints are lower, and the new caliber is without a rim like the 7.62×54 mm R. His work probably began in 1944 and quickly led to the proposal of a carbine that would be tested on the first Belarusian front in the spring of that year and by the officer training school “Vistrel” (“Выстрел”, literally “shooting”). This carbine is significantly different from the ones we know: it is equipped with a muzzle brake (like the AVS-36), a gas tube that cannot be removed at a user level and lacks the folding bayonet that is so characteristic of the weapon today. While this carbine is not without its flaws, the feedback is very positive. The simplicity of the weapon and its tactical advantage (compared to a Mosin-Nagant) are highly praised, but the weapon is still susceptible to exogenous fouling (we’ll detail why later).

Among the weapons offered by its competitors, the carbine designed by M.T.Kalashnikov was indeed tested between 1944 and 1945. Without being devoid of quality, it had not reached the maturity of S.G. Simonov’s weapon, which was based on nearly 20 years of work in this field. As a result, after a few modifications that gave rise to the weapon we know, S.G.Simonov’s carbine was “validated” before the end of the war by the Red Army and was officially adopted in 1949. Its name will be “7,62-мм Самозарядный Карабин системы Симонова образец 1945 года” (“Samozaryadny Karabin sistemy Simonova, obrazerts 1945 goda” or “Semi-automatic Carbine Simonov system, model of the year 1945”). The official abbreviated name will be “СКС” in Cyrillic, or SKS in the Latin alphabet. It can be noted that the “validation” and the official adoption are spaced almost 4 years apart: but in reality, once the war is over, the priorities are no longer the same. It was in the same year 1949 that the weapon was put into production at the Tula plant, then in 1951 at the Izhevsk plant. 1949 was also the year that saw the start of production of the “AK-47 type 1” in Izhevsk. Both weapons were put into service with the Soviet army at the same time. Contrary to popular belief, the SKS was not the first 7.62×39 mm weapon put into service in the Red / Soviet Army: it was in fact preceded by a few months by the “RPD” light machine gun: validated in 1944, the weapon was put into production in 1948 at the Kovrov factory.

For his work on the SKS, S.G. Simonov was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1949, together with M.T. Kalashnikov for his work on the AK and V.A. Degtyarev for his work on the RPD. The latter, who died on January 19th, 1949, received this award posthumously.

From “Weapon System” to “Unified Weapons System”

The 3 weapons were thus put into production and began to be distributed almost at the same time (Pic.03). In fact, this set is designed and adopted as an “infantry weapon system” around the 7.62×39 mm ammunition:

Annual subscription.

€45.00 per Year.

45 € (37.5 € excluding tax) Or 3,75€ per month tax included

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!

Monthly subscription

€4.50 per Month.

4.50 € (3.75 € excluding tax)

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!