The Reising Model 50 submachine gun, .45 ACP caliber

Like many nations, the United States of America adopted a submachine gunSubMachine Gun More for its armies in the late 1930s. The choice fell on the already legendary “Thompson”, then better known for feats of arms in a criminal context (on both sides of the law!) linked to prohibition rather than for military actions. But in reality, by adopting the Thompson, even later in the simplified versions as M1 and M1A1, the United States chose a weapon ultimately ill-suited to military use: heavy, bulky, expensive to produce, and whose ergonomics proved rather unwieldy. It is only natural that some other manufacturers would seek to dethrone the legendary “Chicago Typewriter“.

A context nevertheless propitious

Before designing his SMGSubMachine Gun More, Eugene Gustavus Reising had worked at Colt and with John Mose Browning on the design of the Colt 1911. He was fired from Colt in 1913 for competing using a weapon from a competing manufacturer (a Luger!). A talented competitor, he worked on .22 LR pistols of his own design until 1925. That year, he would know troubles with the justice of his country which would lead him to serve a sentence of 15 months! His debt to the company settled, and after working on many projects without a future, it was in 1938, the year of the adoption of the Thompson M1928A1 by the American army, that he began his work on a submachine gunSubMachine Gun More. The fruit of this project would be submitted to the manufacturer Harrington & Richardson who would begin production of the Model 50 in 1941: on December 7th of the same year, the attack on Pearl Harbor dragged the United States into war. The weapon would be available in two other .45 ACP variants: the Model 55 with folding stock without bearing compensator, and a “semi-automatic rifle” version, the Model 60. Finally, the range is completed by a semi-automatic weapon in .22 LR, the Model 65. According to the sources, about 100,000 or 120,000 weapons were produced until 1945 plus some thousand copies after the war to satisfy foreign orders (the last production dating from 1957). A significant amount for a weapon that would ultimately know an ephemeral use in the armies of Uncle Sam.

Indeed, it was only briefly employed by the US Navy, and in particular among its Marine Corps. The affair took place more precisely on the Pacific front, at the beginning of the American involvement. These weapons had been hastily acquired mainly to compensate for the lack of availability of the service Thompson. Among the Marines, it seemed to not have given any satisfaction, to say the least. The weapon had proven particularly unreliable on the ground (for various reasons that we will detail), something obviously prohibitive for a weapon of war. From our point of view, this is not the only problem with this weapon for military use. In fact, for the soldier, it actually has only two advantages:

- Its weight: weighing 3.4 kg with an empty magazine, nearly 25% less than the 4.5 kg advertised for a Thompson M1A1! Clearly a light weapon, a real plus for the daily life of the soldier.

- Good shooting results: equipped with a 279 mm (11 inch) long barrel excluding climbing compensator, a comfortable wooden stock, with a reasonable stock angle and closed-bolt firing with a light bolt carrier group, the weapon behaves more as a light rifle than a submachine gunSubMachine Gun More.

From a logistical point of view, it is less expensive to produce than a Thompson. But over this, the weapon seems unsuitable for a warlike use: it is prone to fouling, ergonomically uneasy, mechanically imperfect and, finally, unreliable. We will come back in detail on each of these points, but in any case, following very negative feedback, the weapon would be withdrawn from the front for the Marines at the end of 1943. Lieutenant-Colonel Merritt A. Edson even ordered his men to throw their Reising into the Lunga River on Guadalcanal Island!

In addition to the Marine Corps, the weapon would be distributed sporadically to other units including the OSS, purchased in small quantities by Canada… and even supplied to the Soviets under the “Lend-Lease”. After the war, some of its weapons would be re-used by the U.S. Coast Guard and would continue to be used by various law enforcement agencies throughout the United States, but also in different corners of the globe. An available weapon, even an imperfect one, is better than no weapon at all. Our copy is reputed to have arrived, with nearly 200 other copies, from Burma. It shows no obvious signs of wear: traces of manipulation, certainly, but a barrel and internal mechanics in a like-new condition. Unlike in the Marines Corps, it seems to have been successful in “Law Enforcement” type jobs. But is it necessary to specify that the conditions of employment generally have nothing to do with each other?

Bold technical choices

As already mentioned on our site, the devices used on the breech mechanisms of an automatic rearming weapon all meet the same imperative: give time to the bullet to leave the barrel before making a critical opening of the chamber in the face of the pressure present inside the barrel. If the simplest trick is to oppose an adequate mass to the recoil of the case, it includes in essence its main pitfall: adding mass. And what’s more, mobile mass when firing! The exercise is therefore easily achievable on low-power weapons… but reaches its limits with weapons in 9×19 or .45 ACP: it is feasible, but not optimal.

The Thompsons in 1921 and 1928 used an advantaged mechanical system – called “Blish System” after its inventor – but with a very low yield and therefore much more problematic (in terms of production) than efficient (in terms of final result). It is therefore logical that the simplified Thompsons of the US Army, the M1 & M1A1, would do without it. For its part, E.G. Reising opted for the use of an infrequent system… which will make us spill a little ink here!

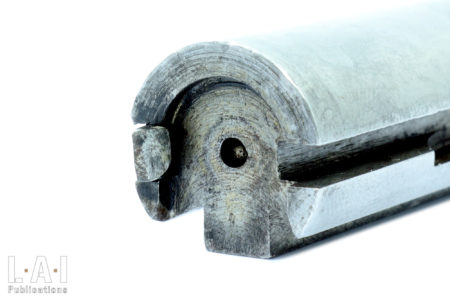

As on most submachine guns, no locking so to speak. Instead, at closing, the rear part of the bolt is positioned in a machined housing in the upper part of the receiver under the action of the control part constituted by the cocking lever (Pic.04). The bottom of this housing has a strong fillet, and the rear part of the bolt has a wide chamfer with a slight fillet in its upper part. Thus, when firing, the connection between the receiver and the bolt itself is not a lock, but a ramp. To move back, the bolt must first slide on this ramp before it can continue its way into the receiver. In doing so, during this “slide”, part of the energy of the shot is transmitted to the receiver (and therefore to the user’s body in the form of recoil), which decreases the amount of energy transmitted to the bolt itself when the pressure peak occurs inside the barrel. And it works: the BCG, consisting here of the bolt (181 g), the bolt carrier (160 g) and the hammer (do not forget it! 57 g), weighs only 399 g (Pic.05). This is very little compared to the 846 g of a Thompson M1A1, the 844 g (approximately) of an M3 Lamp Guide also in .45 ACP and even the 627 g of a STEN (what is more, in 9×19 mm)!

We can read in the English Wikipedia at the time of publication of this article that the “delay blowback” would be produced by a mechanical advantage (i.e. a leverage effect) and by the friction of the bolt on the receiver. If there is necessarily friction, they ought to be minimal: because it would mean at each cycle a significant wear of the mechanism, at a place that in this weapon defines the headspaceDistance between the rear support surface of the ammunition ... More. This area of the receiver is thus ice-polished… by shooting at least in part! In our opinion, this is potentially the big flaw of the system: it may lead to a premature wear of a small area, but which consequences can be highly problematic. However, it is necessary to relativize the thing by asking the following question: what lifespan to attribute to the weapon? And let’s be reassuring, the wear does not seem such that the weapon can be out of service after a few magazines … There are probably several thousand shots, even tens of thousands of shots of potential from this point of view! As for a mechanical advantage, the question is simple: by what means? There is no lever or roller here to multiply the inertia of a supposed additional mass. The bolt is in direct contact with the receiver on its rear part during firing, which cannot be the case of a mechanical advantaged system. The bolt carrier is also in direct contact with the bolt, which cannot be the case for a mechanical advantaged system. Normally, a mechanical element, making the interface between these two parts, generates the gear ratio. Here, again, such a thing is nowhere to be found. Finally, it should be noted here that if this system is not used a lot, it is still found on a weapon that prefigures SMGSubMachine Gun More: the Villar-Perosa 1915!

The operating system is not the only interesting mechanical point. Unlike a majority of pre-war SMGSubMachine Gun More, this one fires from a closed bolt, implementing a linear hammer. It adapts brilliantly to the fact that the rear part of the bolt shifts to the closing. Indeed, the center of the linear hammer, a fully turned part, is hollowed out on a diameter slightly larger than that of the firing pin heel carried by the bolt (Pics.06 and 07). Therefore, if the bolt is not engaged in its housing inside the receiver (and therefore not in the closing position), then the firing pin cannot be operated by the hammer! Intelligently built-in safety. It should be noted here that closed bolt firing is undoubtedly a plus in terms of improving shooting results (and therefore the hit probabilities). Indeed, there is no slam of the bolt when firing. Plus, it means the ejection port never stays open! So, it’s a better point against fouling. Unfortunately, we will see that the weapon is not ideal from this point of view later… In addition, this choice considerably complicates the firing system… And here too, the result is not ideal…

This firing system uses “classic recipes”: a trigger that controls a sear, all being subject to two commands:

- A connecting bar that connects the trigger to the sear and that is disconnected from the trigger on each cycle: this creates the semi-automatic mode. The reconnection between the parts is ensured by the trigger’s return.

- An automatic fire control: when the selector is in automatic mode, and if the trigger is pulled, then the automatic fire control hooks the bolt carrier on its return, generating the sear release at the end of the stroke.

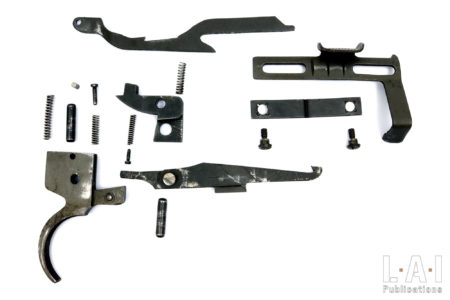

Everything is done – sorry to say – without genius from a mechanical point of view: there are finally many parts and springs (selector included): 17 parts including 5 springs (Pic.08). And on our copy, the whole experiences a lot of frictions…

The percussion is of the hit / pressed type. The firing pin is, however, equipped with a strong return spring, the purpose of which here is undoubtedly to ensure that the firing pin does not protrude into the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More during the feeding phase (Pic.09). Indeed, on the Reising, the feeding would be controlled. The ammunition is therefore taken into account on the lower part of the bolt and its ascent to the chamber by sliding on the bolt faceThe bolt face is the part of the bolt which in set place the... More (Pic.10). From that moment on, the firing pin must not obstruct the cartridge head on its way. Unfortunately, the weapon feed is not a model of its kind: evidenced by a “double” feeding ramp: one on the barrel, one on the receiver (Pic.11). Ideally, the ammunition’s presentation should be as in line with the chamber as possible, and at least avoid the use of “steep” feeding ramps. This is the case here! On this side, the Thompson had the “presence of mind” to use a long feeding ramp (like a day without bread, probably a record), but very progressive! This has the disadvantage of lengthening the weapon, but fluidifies the feeding, and therefore makes it more reliable.

The extractor / ejector set is also very classic: the extractor, a long spring blade screwed on the bolt and the ejector a fixed element reported on the receiver.

A weapon that makes massive use of stamped sheet metal, really?

Let’s be blunt immediately, to highlight that the productive advantage of this weapon is based on the use of stamped sheet metal is… A big scam. If we point this out, it is because it is what can be read on Wikipedia (English version, always…) at the time of writing. We even wonder if the people who wrote these lines ever had the weapon in hand or the skills necessary to understand the subject… anyway. And yet the thing is written in the mother tongue of the country where the weapon comes from… Surprising that no one has corrected this error at the time of publication… (28 June 2023… Screenshot can be provided if necessary…)

No, the weapon is mainly made of machined steel parts, distinguishing itself above all from the Thompson by a manufacture mainly carried out by lathing and not by milling and by a notable (but not major) use of welding. Sheet metal parts are ultimately few and of relative importance (in terms of productive gain). They can be inventoried: the trigger connecting bar, the rear sight cursor, the firing selector, the magazine latch, the trigger guard, the stock screw washer, the butt plate and of course the constituent elements of the magazine (Pics.12 and 13). We can add to this a leaf spring shaped into the eyepiece itself. The climbing compensator is not stamped sheet metal, but a shaped and machined steel tube: an elegant technical solution, certainly, but it is not stamped sheet metal. The magazine well is made from a square tube welded on a plate (Pic.14). Still no stamped sheet metal. The centerpiece of the weapon, the most massive and among the most expensive, the receiver and its 4 feet (brought back by welding), are lathed. The same goes for the bolt, the linear hammer… and obviously the barrel (difficult to do otherwise in this latter case…Pics.15 to 17). Clearly, lathing is the dominant manufacturing operation of this weapon. Is this a defect? Certainly not! As already mentioned in the article about the Italian FNAB-43 SMG, the essential thing is to find, in a given context and with available tools, the best compromise for fast and inexpensive production depending on the scale of production envisaged. For mass productions, it should be noted that speed of production and low final cost often go hand in hand, but not necessarily for confidential productions. This is explained by the investments sometimes necessary in specific tools for large-scale productions that could not be absorbed on small quantity productions. In this case, lathing is more economical than milling… So, given the industrial context of the early 1940s, mission accomplished! And besides, we can find as information (on Wikipedia… so beware), that the Reising SMGSubMachine Gun More (which model and on what date?) cost $ 62 to produce where the Thompson (which model and on what date?) cost $ 200 … about 3.2 times less… If the overall information is undoubtedly true (i.e. Reising SMGSubMachine Gun More costs less to produce than Thompson SMGSubMachine Gun More), it is advisable to be wary of such inaccurate information… ah… Wikipedia…

So, from an industrial point of view, there is no doubt, the Reising M50 has a considerable advantage over the Thompson, even in its simplified version. What’s wrong is elsewhere… Even everywhere else!

Some sources indicate that during WWII, the parts of the firing system were prone to breakage and loss in the field. We cannot probe souls, kidneys or matter, but the first part of the assertion seems unlikely to us: the mechanically solicited parts are of good size and do not seem to present any particular fragility. On the other hand, the system is quite complicated to disassemble in the field… And very often, the breakage of part comes from a bad reassembly, or even an unnecessarily “manly” reassembly … Witnessed by your servant during training courses! For the second part of the assertion: yes clearly, some parts are too small and are easily lost… in a workshop! As for the field …

It must be added to this that the weapon would likely be produced with manufacturing tolerances too tight, requiring adjustment by hand, weapon by weapon, which would make the interchangeability of parts impossible in the field. If the thing seemed surprising at first sight given the era, it is clear that the thing seems to be accurate. In addition to the recurring testimony of the Marines’ bad experience in the Pacific, the copy at our disposal quickly presented problems after a first advanced disassembling at the end of the shooting session. Without loss or degradation of parts, once reassembled, the reconnection between the trigger and the connecting bar was no longer possible, the bar not moving back enough, or the sear having moved too far back. And we searched, again and again, for a possible mistake on our part (I’m not perfect) … But there were none. The weapon is permanently stopped, unless you take things back to the file to re-adjust the parts … (which eventually happened). Having started my professional career in this field in 2004, after having handled many, many weapons (the center for which I was in charge of the workshop treated between 4,000 and 5,000 weapons per year, speaking only of the service weapons …), it is a first! Champagne!

However, to make this assertion peremptorily, it would require a more complete testing chart (with several weapons) than the modest analysis we propose here.

In the end, in general, the internal mechanics of the weapon leave no room for grime and according to our experience, absolutely does not tolerate the lack of oil: as already mentioned for the firing system, there is a lot of friction between the different parts, which consequently grips very easily. And as we write these lines, one piece of information resonates in our mind: E.G. Reising was first and foremost… a competitive shooter. It thus seems obvious to us that, in absolute terms, we are not dealing with a weapon conceived as a weapon of war. And the mistakes don’t stop there…

Singular ergonomic choices

In our opinion, we are hitting rock bottom… at least, for a weapon of war. And let’s start with the choice that seems the least understandable and the most harmful: the charging handle (Pic.18). This is positioned inside the lower part of the handguard. The part to be operated offers only a limited gripping surface. Worse, the maneuver can only be performed at your fingertips, where the body has little resistance to stress. The matter is therefore not easy, even during peacetime. Add to it, humidity, cold, fatigue, stress … And clearly, we are getting closer to the worst. Yes, there is also the Guide Lamp M3 second model SMGSubMachine Gun More where cocking is done by introducing the finger into a housing (fortunately wide!) inside the bolt. Having tested both, the Reising one is much worse…

If the device is installed deep enough in the handguard so as not to interfere with the off-hand when firing (because the handle is of a reciprocating type), this wide opening offers direct access to the recoil spring assembly… for dirt! For something that will often be close to the ground, or even on the ground… Thus, if the bolt of the Reising SMGSubMachine Gun More remains closed, thus avoiding fouling, the opening by the cocking handle is permanent and wide…

The installation of the cocking handle therefore offers in our opinion, no advantage, especially if we consider that in fact, a cocking handle present on the side of the weapon, even of a reciprocating type, does not offer overall disadvantage. Better, when it is solid, it allows the resolution of some shooting incident by a “manly” maneuver (forgive me, ladies, for these overflows of testosterone …). Outside here, the maneuver is already complicated in normal times… So, with, for example, a case stuck in the chamber… And let’s not underestimate the effects of oxidation and grime.

The weapon does not have a bolt stop… A device whose usefulness is perfectly questionable on a weapon of war… even counterproductive! We refer those interested in the question to Chapter 6 of our book “Small Guide for Firearms”… Let’s avoid repeats! So, from our point of view, a good point. In the end, it will be 1/20 (TN: French grading system, really close to an E) …

The magazine latch, economical from a production point of view, is a horror to handle (Pic.19). Already, at the grip, we do not know whether to press or repel it. Both maneuvers are laborious but allow the magazine to stall. We will still prefer to repel it: the thing is less instinctive but requires less muscular effort. The gripping streaks are also much more marked in this sense, but it remains … laborious.

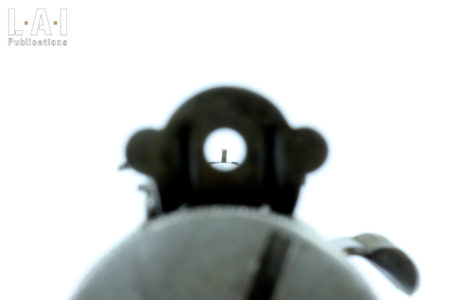

The adjustment of the rear sight requires… both hands… It is indeed necessary to lift the aperture to be able to move the cursor (Pic.20). The operation is impossible to do without leaving the firing position, whatever it is… Well, we can rationalize the thing by saying that being a .45 ACP SMGSubMachine Gun More, it may not be a rear sight to accommodate the shooting distance (even it still looks like it!), but maybe an initial adjustment device: we set to 100 m, and that’s it! It is also noted that the rear sight has no marking concerning possible distances. The front sight blade is adjustable in direction: we loosen an Allen screw (yes, in 1941!) and we slide the front sight in its dovetail (Pic.21). All in all, the sights are suitable for shooting, but we regret that it is not protected at all… Again, for a weapon of war, too bad… Moreover, the front sight of our copy, which has obviously not known any use on the field, is already damaged (visible on picture 26).

The fire selector is installed on the upper right rear part of the receiver (Pic.20 and 22). It has three positions, from front to back: F.A. (“Full Automatic“), S.A. (“Semi-Automatic“), and SAFE. When the weapon is well lubricated, its maneuver is… feasible, but the drawing of its cursor is clearly unpleasant to the touch. When the weapon is a little dry, it is an ordeal: frictions are omnipresent. We regret the lateral levers of the Thompson … which are not the most practical either! Let’s not forget that in a military context, safety is an important device: you will get to move with your chambered and cocked weapon in combat, with the safety on. It is highlighted that the selector would have the disadvantage of not allowing easy tactile identification of its position (therefore by low visibility condition). Certainly, but it is possible to ensure one’s position by one’s action… provided you know how to count to three and know your weapon … We are quick to criticize, but when it seems to us to be justified. Outside there, it seems a little far-fetched. The real problem for us is that its action is not the easiest.

The case of the magazine

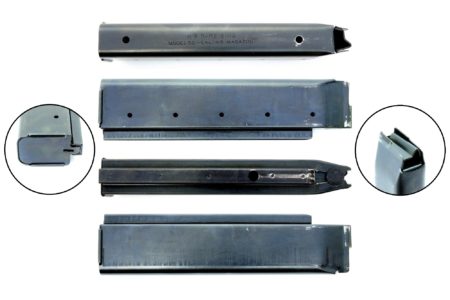

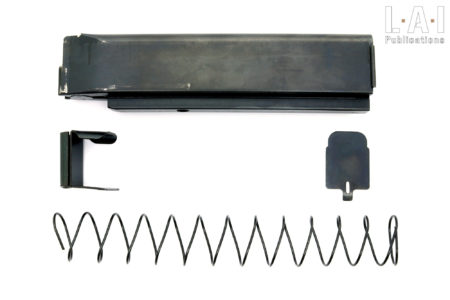

Let’s deal here with a rather special case: the weapon made available does not have original magazines, but reproductions of the 20-shot magazine made in Asia (not having the certainty on the producing country … – Pics.23 and 24)! Rather good-looking on its external appearance, it seems to sport the specificities of the original magazine … and even some of its markings! Shouldn’t we talk about counterfeiting? Not so sure, because the markings only take the brand and the model of the weapon, the caliber … but does not claim to be manufactured by HARRINGTON & RICHARDSON ARMS CO. WORCHESTER, MASS. U.S.A.! From a functional point of view, this works… pretty much. The follower is roughly made (no deburring… for a part that slides!) and it seems obvious on examination that the spring is weak, the thing being confirmed by firing as we shall see later. For the rest, it takes the specificities of the original magazine: double stack / single feed. It seems that the original magazine was also not satisfactory: it was regularly replaced by a single stack magazine of 12 shots, with similar external dimensions, but with strong ribs on its body to reduce the capacity by switching it to single stack. The goal is, of course, to reduce internal friction and to manage grime.

Here, the choice to make a proprietary magazine (i.e. specific to the weapon) with double stack / single feed can question insofar as the box magazine of the Thompson, with double stack / double feed, is certainly not the worst thing of the weapon. It was even rather one of its strong points! What’s more, the magazine of the Reising even takes some specificities from the Thompson’s:

- The rear rib, which allows the passage of the control allowing the bolt stop of the empty Thompson magazine (by disconnection of the sear … nothing less!) is relegated to the role of magazine insertion stop.

- The bottom plate is identical in design.

So even if you were inspired by the Thompson’s magazine, why did you reduce it to single feed? The answer probably lies in the width of the receiver, which is narrower than a Thompson’s. The firm Guide Lampe would make the same choice for its M3. In both cases, it is the opposite of the rather natural evolution of SMGSubMachine Gun More magazine: while many pre-war SMGs offered a double-stacks / single-feed, nowadays all SMGSubMachine Gun More manufacturers use double-stacks / double-feed. And it is all the more interesting, because to our knowledge, before the war, the Italians, the French (do not chuckle too quickly …) and the Americans had “hit right” from the start, with double-feed magazines on their first SMGSubMachine Gun More. Only Italians would remain faithful to this magazine design until today, and without hesitation! And in a perfectly reasoned way in our opinion: these magazines reduce the friction surfaces to two (contact with the next ammunition and contact with a lip) against three (on both lips of the single feed in addition to the cartridge). As a result, the release of the ammunition can be done much easier, thus without unnecessarily slowing down the bolt group. Finally, these magazines are much easier to fill, by simply pressing on the ammunition. In the United States and France on the other hand, there will be a technological downshift to put into service magazines very close to the design of the magazine of German SMGSubMachine Gun More … which are clearly not the best! If these magazines are solid, they are laborious to feed (hence the recurring use of a charger for these magazines) and source of many breakdowns in use … Finally, if in the case of the MAT-49 and M3, the magazines take advantage of the transition to the single-feed to strengthen their lips … this is not even the case with Reising! For the UD M42, the lesson seems to have been well learned: its magazines would be a 9×19 port of Thompson’s .45 ACP magazines (Pic.25). No more, no less.

Shooting

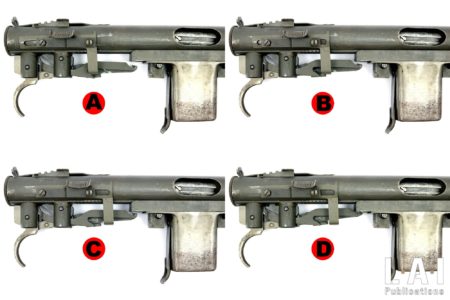

All reservations expressed on ergonomics aside (because already mentioned), the weapon is clearly pleasant to fire. We feel a real “carbine” vocation to this SMGSubMachine Gun More, but without being unpleasant in full automatic, quite the contrary. The sights “do the job”, with a certain rusticity (the aperture is very wide, the front sight is devoid of a framing element), but which does not seem fundamentally incompatible with a warlike use (Pic.26). After a first stroke, the trigger release is direct and heavy, but again, in accordance with a warlike custom. The recoil is obviously small, the imposing climbing compensator (allowing to take advantage of the little energy of the gases available at the muzzle by a large surface of action) finishing to keep the weapon in line (visible on Pic.21). Note here that in the batch of weapons from which our copy comes, there are what seem to be Model 55 mechanics (so without compensator) on Model 50 stocks (Pics.27 and 28)! The thing would be interesting to fire… Stay tuned! In bursts, the rate of fire is not excessive (789 rpm), everything is fine, it is very controllable … This weapon is much more pleasant for us to shoot than the Thompson, which in addition to its weight, its excessive offset of the barrel, has a stock much too long for our size of 1.74 m measured during the last medical examination …

The hit probabilities are in line with what should be expected with this type of weapon: it easily “reaches” a silhouette at 100 m. No need to say more, especially about the examination of a single copy and more than 70 years old, although in almost new condition! Make no mistake about the nature of the work: it is indeed a technical and global analysis, starting from a single copy, and not an evaluation scored in the context of a call for tenders on a panel of several copies.

In addition to the problem of the firing system already mentioned, we have had to deplore some shooting incidents: but these seem to be related to the magazine, which is not original and of perfectible quality as already exposed. The problem was related to an imperfect presentation of the cartridge, resulting in a stop of the bolt on the ammunition (the rest of the weapon cycle being normal). As expected, the springs of the magazines at our disposal are probably too weak in addition to having a follower that hangs in its ascent. After identifying the problem, we lubricated the walls of the magazines more abundantly (but without excess) to facilitate the ascent of the ammunition as well as their distributions and the problem disappeared… at least for the end of the shooting session. Here too, let us not exceed the limits of our exercise: the goal is not to perfect the weapon to make it functional, but to account for our experience with the equipment we had available in the state in which we perceived it. Yes, in absolute terms, the defects of the magazine are correctable… But it’s not my war!

In general, in slow motion, it can be clearly seen that the bolt slows down too much when meeting the ammunition in the magazine. Without knowing if this phenomenon is related to these magazines in particular, or recurrent on the weapon, we can make several observations here:

- Clearly, this is detrimental to the reliability of the weapon, the feeding must be done in the smoothest way possible. Ok, that’s obvious… But still, it had to be said!

- If this is related to these magazines in particular, then the rate of fire of the weapon with original magazines must be higher than that measured, in an unknown proportion, but still significant. It should be noted that the rate of fire observed (789 rpm) is already much higher than the one announced on some documentation (550 rpm) … like Wikipedia… Yes, again. But if no one says that this source is choke full of errors, then no one will ever correct them (and then again, it’s not my war!). But there is no doubt that here too, as we have already seen, someone will take back the fruits of our work (and it is totally legitimate, and we do it for this purpose among other things) … but without ever quoting us (oh… Ain’t that strange! A real classy move, right ?) Not to mention the prejudices it brings…

- As already mentioned, the angle of introduction of the ammunition seems, in any case, too important.

At the risk of pushing an open door open again, feeding and magazine are probably among the most complex things to design on an automatic weapon. There are many reliability issues associated with this. Here, the choices in this area really question.

Disassembling and maintenance

Here, the result is mixed. On the one hand, disassembling operations do not pose any real difficulty… in the workshop! On the other hand, they are clearly too convoluted to be carried out serenely on the battlefield… In any case, no emergency disassembling can be undertaken with this weapon… even summary. Disassembling the bolt simply requires removing too many parts. In absolute terms, we are very close to what can be done in disassembling for purely civilian weapons such as a .22 LR semi-auto rifle… or worse, a semi-automatic hunting rifle…

After checking the weapon and the magazine for ammunition, the following can be done:

We will start by removing the stock:

- Remove the magazine from the weapon.

- Unscrew the stock assembly screw on the back of the magazine well. This screw being knurled, this operation can normally be carried out by hand. Once unscrewed, this screw remains captive to its support washer, itself nailed to the stock.

- Remove the stock from the bottom of the weapon following the magazine well and its latch.

We can then remove, the receiver cap, the linear hammer, its spring and its guiding rod. It is noted that the operation can be performed with a cocked hammer without real additional difficulty, the long unscrewing of the cap allowing a sufficient decompression of the spring:

- Unscrew the cap in order to remove it.

- Remove the hammer spring and its guiding rod.

- Tilt the receiver down and press the trigger all the way: the hammer comes out of its housing. We will oppose the hand to the end of the back of the receiver to recover the hammer, but I did not do it on the video for visibility reasons.

That was the “easy” part… Let’s hit the nasty stuff.

Disassembly of the bolt carrier group. To do this, it is necessary to remove the magazine well:

- Bring any metal rod with a diameter of less than 2.00 mm… An unfolded paper clip will do the trick.

- Push back the charging handle until a hole appears on the recoil spring’s guiding rod and insert the metal rod. Then, release the assembly.

- Using a hammer and a bronze pusher, remove the two elastic holding pins from the magazine well. Before striking like a brute, try both sides gently: on our copy, the pins came out more easily on one side than on the other without this being able to be identified beforehand.

- Remove the magazine well.

- Rotate the bolt carrier (i.e. the cocking lever) towards the bottom of the weapon to dislodge it from the bolt, then remove it by pivoting around the elements of the firing system, maneuvering them if necessary.

- Tilt the receiver down and press the trigger all the way: the bolt comes out of the receiver. Here too, we will oppose the hand to the end of the back of the receiver to recover the bolt, but I did not do it on the video for visibility reasons.

Finally, we will add the disassembly of the magazine (at the end of the video of the advanced disassembly):

- Using a suitable tool (for example, a watchmaker’s hook), take out the rear end of the magazine floorplate, and slide it backwards to cross the locking threshold.

- Once the locking threshold is crossed, oppose the thumb to the bottom of the magazine and remove the magazine floorplate.

- Remove the magazine spring and the follower.

The field disassembly of the weapon is completed: we can move on to the advanced disassembly:

On the bolt, the firing pin can be removed in a very simple way:

- Press the firing pin heel, and remove its pin (on our copy, it was not necessary to use a hammer).

- Remove the firing pin and its return spring.

The firing system can be disassembled without any real difficulty… other than to avoid losing certain parts:

- Holding the trigger in position, remove its axis. The thing is realized without a hammer on our copy. Once the axis is removed, remove the pusher, taking care to accompany the trigger: some parts will want to take off when the trigger is released…

- Remove the trigger assembly and its connecting bar.

- Remove the axis from the connecting bar and then the bar itself.

- Remove the return spring from the bar accompanied by its plunger.

- Remove the trigger return spring from its housing: on our copy, it is flared on one side to avoid being lost. A pusher is inserted into the spring beforehand to avoid destructive twisting of the spring.

- Remove the sear axis. Once the axis is removed, remove the pusher, taking care to accompany the exit of the sear and the automatic fire control: some parts will want to take off when the sear is released… Yes… again…

- Separate the sear from the automatic fire control.

- If the sear return spring has not fallen out during disassembly, remove it from its slot in the sear.

- Remove the automatic fire control return spring and its plunger from its housing in the receiver.

- Unscrew the two screws on the fire selector, then remove the selector and its spring.

The magazine latch can be disassembled:

- Unscrew the magazine latch spring screw, then remove the magazine latch and its spring.

The recoil spring and its guiding rod can be separated from the bolt carrier by removing the metal rod (re-assembling is not complicated)

Finally, the rear sight cursor can be removed, without prejudice to the initial adjustment: the aperture is lifted, and the cursor is slid backwards.

Advanced disassembling is complete (Pic.29). We could add the disassembly of the front sight, but this would be at the cost of losing the initial setting… So, do it only in case of extreme necessity. We regret the impossibility of disassembling the extractor at an advanced level: this can only be done in the workshop with spare parts, its holding screw being pointed, just like the screw fixing the rear sight.

The assembling operations are done in reverse, taking care not to forget the plungers on the springs of the connecting bar and the automatic fire control. Regarding these plungers, it is also interesting to note that the one of the automatic fire control is sometimes presented as the trigger return spring plunger, and this even on the weapon exploded view! This is very curious: because from a mechanical point of view, this makes no sense (the spring is already supported on a flat and motionless surface of the receiver) and its very dimension, does not correspond to the said return spring: the plungers are much smaller in diameter! However, as it can be seen on the video, the size of this plunger corresponds perfectly to the housing of the return spring of the connecting bar, location where it finds a rational function: that of distributing the effort on the bar on the entire end of the spring … Decidedly, this weapon and everything around it seems very curious.

The accessibility for cleaning is very correct: only the part around the ejector has some minor difficulty, but this is common on many weapons using a fixed ejector in the receiver.

In conclusion

So, is this SMGSubMachine Gun More better than the Thompson? No, clearly, in keeping with its reputation, we are facing one of the worst submachine guns we have ever had the opportunity to analyze and fire with. Be careful, the weapon is not devoid of interest and explores interesting tracks: but the final result is not in line with what should be expected from a weapon of war. And despite these flaws, the Thompson (especially the service M1 and M1A1) remains more suitable for war use. Staying in the United States territory and over this same period, we would heavily favor the Guide Lamp M3 SMGSubMachine Gun More, which in addition to being a very interesting industrial tool (sheet metal, for real, few parts …) is astounding at the shooting range! Be careful, this weapon too, is not free of defects!

Arnaud Lamothe

Sources:

Well, you got it… I looked a lot at what we find on Wikipedia (in English… let’s not even talk about French): I hope that the historical details are more reliable than all the technical details…

For those who want a more serious source on the work of Eugene Reising (but which still seems to us to be borderline hagiography as the author seeks excuses for the inventor):

https://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/ASOAC-EDITION-119-ALBERT.pdf

Thanks:

The ESISTOIRE Gunshop for the provision of the weapon for this article. Yann, Laura… on top!

Annual subscription.

€45.00 per Year.

45 € (37.5 € excluding tax) Or 3,75€ per month tax included

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!

Monthly subscription

€4.50 per Month.

4.50 € (3.75 € excluding tax)

- Access to all our publications

- Access to all our books

- Support us!