The Webley-Fosbery revolvers

At the end of the 19th century the gunsmith industry experienced significant growth. Recent technical advances were accelerating discoveries, patents and systems. All things considered, a parallel can be drawn with the evolution of computing over the last twenty years of the 21st century. After mastering steels, industrialization, standardization and the development of smokeless powder, the gunsmith industry developed the concept of semi-automaticity. A considerable number of patents were filed, quite a few being the first semi-automatic pistols. It is clear that even if these weapons are today an admirable gunsmith heritage, the lack of reliability and complexity were often to be deplored. It was not until 1893 that the first “reliable” semi-automatic pistol was born: the C93 Borchardt.

A “simple” idea

As is often the case, good ideas are based on simple, common-sense concepts. At the end of the century, most revolvers in service were reliable. Therefore, by creative genius or pragmatism, the idea blooms to apply the mechanical principles of semi-automatic repetition to revolvers. Several tests were carried out, but the only reliable semi-automatic revolver remained the Webley-Fosbery, the work of Lieutenant-Colonel George V. Fosbery (1832–1907). He was awarded the Victoria Cross at the age of 31 and retired from military duties in 1877. Lieutenant-Colonel Fosery was not at his first invention: in 1885 he patented the Paradox gun. It is a smoothbore barrel but whose last part, usually tighter in diameter to manage the dispersion of the shower of pellets (the “choke“), was rifled. The purpose of this invention, immediately sold to the prestigious firm Holland & Holland, was to improve the performance of the barrel for shooting balls without prohibiting the firing of pellets. This specificity earned it to be often named, instead of “Paradox Gun“, “Ball and shots“. A bit like this half-smooth, half-rifled barrel, the Lieutenant-Colonel’s revolver seems to come from an unnatural crossover…

The strength of this revolver is to combine the qualities of a seasoned weapon and apply a semi-automatic rearmament system to it. If this mechanism is highly complex and fragile on the first pistols, the ingenuity of Lieutenant-Colonel Fosbery ensures the Webley-Fosbery an irreproachable operation combined with a “simplicity” of design. The idea is to make the barrel / cylinder assembly mobile on the frame in order to exploit this mechanical translation to ensure the cocking of the hammer and the rotation of the cylinder. Lieutenant-Colonel Fosbery conceptualized his project as early as 1895, the first prototypes using a Colt Single Action Army revolver base.

The first public appearance of the Fosbery semi-automatic revolver took place in 1900 during a competition on Bisley’s famous British firing range. After some improvements, the weapon met with some success with competitors. It has an increased firing speed and a real reliability of operation. Although it is relatively high on the hand, this revolver is comfortable to shoot and of great accuracy. Books on the subject also relate the exploit of the American competitor Walter W. Winans who in 1902, managed to fire 12 cartridges (so with 1 reload made using a speedloader “Prideaux”, designed in 1893 for the .455 Webley) in 15 seconds by grouping in the target bullseye.

If when first put on the market, the “Webley-Fosbery Automatic” revolver (its name in the first place) has seduced a number of civilian shooters, on the military level, despite the firepower offered, the fragility of the system and especially its intolerance to any foreign object (dust, sand, mud), has irreparably disqualified it. Similarly, one can question, from a military point of view, the real advantage of a “semi-automatic” revolver compared to conventional double-action revolver, less expensive, more rustic and, ultimately, much more reliable. Thus, the Webley-Fosbery would never be adopted by any army. It would nevertheless be present at some places of combat, British officers having acquired it individually as it was common at that time.

The “WEBLEY-FOSBERY AUTOMATIC”: a semi-automatic revolver

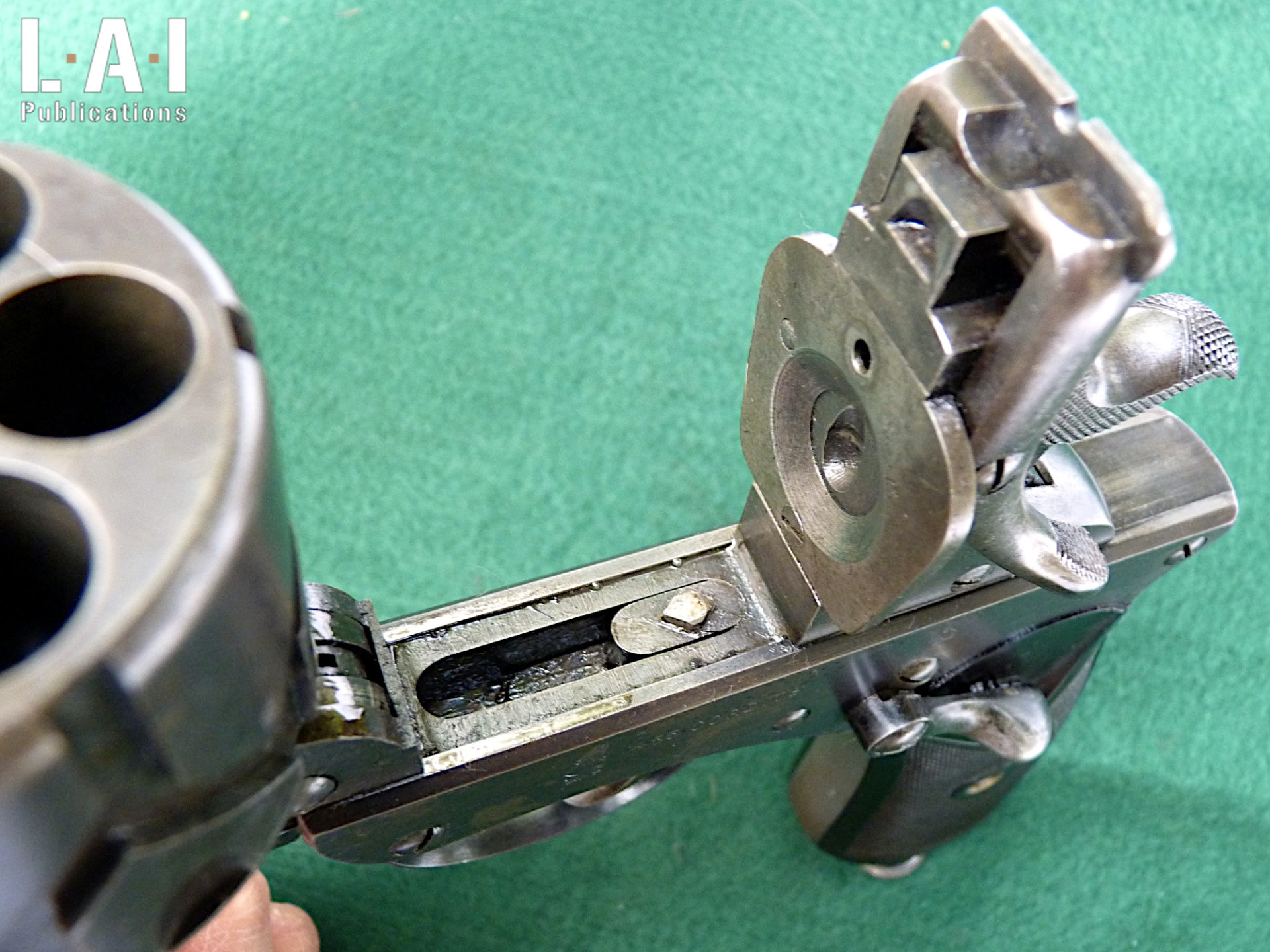

The semi-automatic rearmament of this single-action revolver is based on the direct exploitation of the recoil of the barrel during firing… well, actually, as a majority of “automatic pistols” operating from a locked bolt! For this purpose, the weapon consists of two main parts:

- The frame assembly, butt, trigger guard and slide that makes up the “fixed” part, taken in hand by the shooter.

- The barrel, cylinder and hammer assembly, which makes up the “mobile” part.

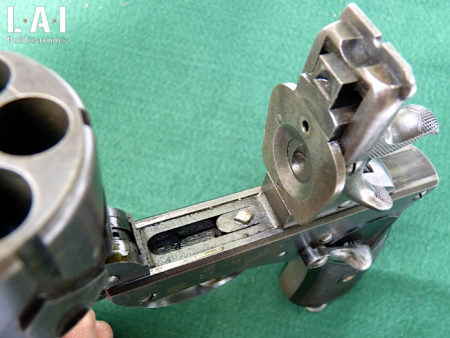

The mobile part slides into the fixed part. It is held in tension by a recoil spring, housed in the lower part of the handle. During firing, the mobile part is therefore driven by the recoil to the back of the fixed part before being sent forward by the recoil spring. On this movement of the mobile part:

- During the backward movement, an extension of the lower part of the hammer encounters a stop attached to the fixed part, causing its rotation and cocking.

- The recoil spring, contained in the base of the handle, is compressed by a long lever.

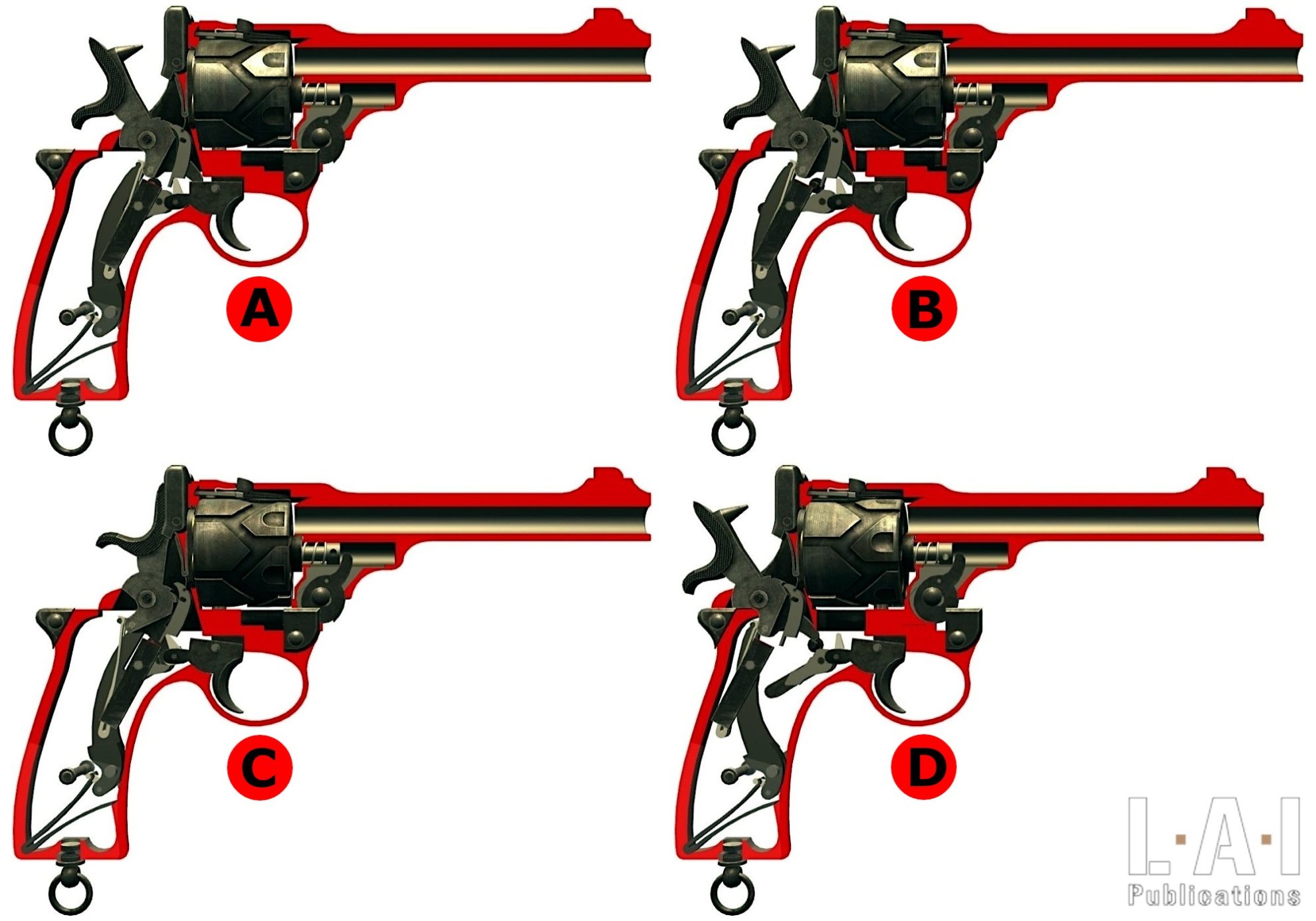

- Following a cam attached to the fixed part, the cam path machined on the cylinder rotates the latter before indexing it.

This barrel rotation system is very inspired (should we say “copied”?) from the Mauser Zig-zag revolver. Note, however, that unlike the latter, the cylinder performs its rotation in two-stroke. Indeed, the drawings of the cylinder grooves ensure a first half-rotation when the mobile part is recoiling, then a second half-rotation and finally its indexation when the weapon is put back in battery under the action of the recoil spring.

The loading of the weapon is, in most respects, classic and, in all respects, identical to the other top-break weapons of the Webley system. The opening lock has a pedal on the left side. Once compressed, it frees the upper part of the frame and allows the barrel / cylinder assembly to be tilted forward. The ejection of the cases is ensured by a collective extractor. It automatically protrudes when opening and returns to its original position only when the tilt is complete.

After loading, as on any single-action weapon, the implementation of the weapon therefore goes through the prior cocking of the hammer. The thing can be accomplished conventionally by action on the crest of the hammer, but another method, more singular, is to take the barrel with the off-hand and compress it backwards… A bit like the image of a semi-automatic pistol slide.

This revolver is therefore by its mode of operation, totally original. On top of it all, it has a manual safety present on the left of the frame. In the form of a lever, it allows the weapon to be transported to a cocked position. This controls the recoil of the mobile part over a short distance, which allows to:

- Disconnect the trigger (and its ratchet) from the sear, in the same way that happens when firing to generate the “semi-automatic” nature of the firing system (the so-called “disconnection” action).

- Position the lower extension of the hammer on the way to the frame stop. Thus positioned, even if the hammer is released, it can not come into contact with the primer, because it would be stopped on its course by the stop.

- Immobilize the mobile part in this position. Thus, the weapon can be handled or returned to the holster without risk of parasitic movement of the mobile part.

We can question the relevance of carrying this weapon ready to shoot, but the case has been studied. This is probably to compensate for the loss of the capacity for “immediate action” conferred by the double actionThe "double action" is a trigger mechanism where the action ... More of most of the revolvers of this end of the century.

A Webley & Scott production

It is the firm Webley & Scott of Birmingham that would produce this weapon, estimated at less than 5,000 pieces, from 1901 to 1924. This firm was already producing, under contract with the British government, the service revolvers of the imperial army (at the time of the production of the Fosbery, the Mk.IV of .455 Webley caliber), but also revolvers for civilian use, such as the RIC. Many variants have been marketed, they are generally listed by collectors (but not by the manufacturer!) according to the following nomenclature:

- The 1901 model, in caliber .455 Webley at 6-round.

- The 1902 model, in caliber .38 ACP at 8-round.

- The 1903 model, which is an improved version of 1901, following the 1902 pattern but in .455 Webley at 6-round.

Let’s add here that our research leads us to think that there is no consensus around this nomenclature. The thing has nothing official, it is not shocking, and it would be futile and pretentious to try to distribute “good points”!

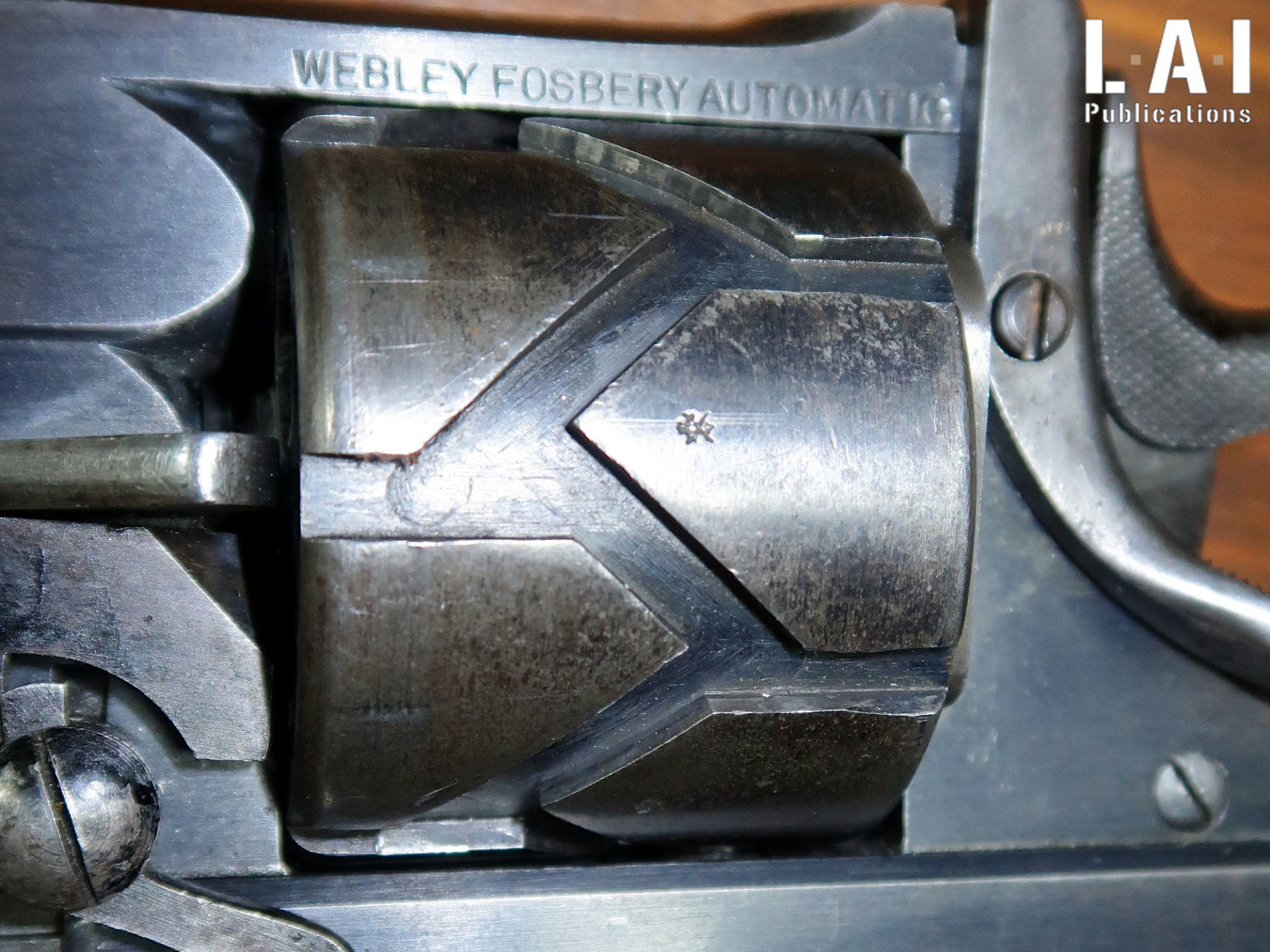

In the vein of many “confidential” productions, each model has production variations (machining of parts, drawing and material of the grips, difference in rate). If some variations in production are of the order of production detail (we can mention here the substitution of the recoil spring from a coil spring by a V-Spring from the 1902 model), some are related to a real evolution of the weapon among which the evolution of the cylinder and its disassembly method.

On the 1901 model, the cylinder removal procedure is inherited from other Webley revolvers. This disassembly is based on the implementation of a lever present on the left side of the weapon which makes it possible to disengage a key of a groove machined on the axis of the cylinder. Unlike the other revolvers of the brand, this lever is not secured by a screw. And for good reason, the mechanical specificities of the “semi-automatic” revolver require more frequent disassembly and maintenance of this part of the weapon. With the appearance of the 1902 model, the disassembly of the cylinder is greatly facilitated: simply press the push button positioned on the frame above the cylinder. This pusher, which also allows to keep the cylinder indexed when opening by means of a pawn coming to lodge in one of the cylinder’s grooves, comes to take the place of a pawn which performs this last function. Indeed, this indexation is essential for the return to service of the weapon: it is not possible to close the revolver if the cylinder is not in front of the cam of the fixed part. The cylinder is therefore also modified: it receives additional machining on the front part which makes it possible to accommodate the stopper. The weapon is thus simpler: from a production point of view, but also from a use point of view.

In addition to the various “cosmetic” modifications of the cylinder (fluting on early productions, drawings of the cam path visible on this site! ) and that previously related to disassembling, the 1903 would be equipped, probably from 1912, with a shorter cylinder. This modification seems to be related to the generalization of the .455 Webley Mk.II ammunition. Indeed, the Webley-Fosbery was originally designed around the .455 Webley Mk.I ammunition loaded with the “Cordite”. If the Mk.I ammunition was initially loaded with black powder, it was loaded from 1894 with the brand new British smokeless powder: the “Cordite”. This Mk.I Cordite ammunition differed from its predecessor “gunpowder” by the presence on the case of a crimping groove for the bullet and by the letter ” C” on the head. In 1897, taking advantage of the Cordite’s performance, the .455 Webley ammunition saw its case shortened and thus became the “Mk.II”. However, we must be clear: this change did not instantly lead to the disappearance of the Mk.I ! Also, the use of Mk.I, loaded with black powder or Cordite lasted for many years. Thus, out of pragmatism, the first Webley-Fosbery were chambered for the Mk.I ammunition with the long case, then more readily available than the very recent Mk.II. However, the weapon bears the mention “455 Cordite” and even “455 Cordite Only” on early productions, which reminds us that the use of black powder in this “automatic” weapon is not recommended. And for good reason, producing a higher fouling, it may lead to frequent stopping. Of course, shorter cylinder means shorter frames!

Different barrel lengths were also offered: 4, 6 and even 7.5 inches for the “Target” model. The “Target” version was available for at least the 1901 and 1903 model: it has a derivable rear sight, while the other versions have a non-adjustable V-shaped rear sight, machined in the frame lock.

The last modification seems to date from 1914, WWI having probably put an end to the improvement of the weapon. A document available on this site, gives an idea of the quantities produced according to the years.

A weapon as accurate as its legend

The weapon we had the “enjoyment” of is a model 1903 Target with a 7.5-inch barrel. The length of the revolver is 30 cm for a mass of 1280 g. As mentioned earlier, the first grip is confusing. The position on the hand is very high, the angle of the butt is also unusual. After this first impression, we adapted very quickly to the grip, the overall balance being excellent. The line of sight is particularly neat. Long enough to exploit the sights, it allows to obtain an effective sight contrast. Although beaded, the front sight allows a comfortable acquisition of the target. Typical of precision weapons of the late nineteenth century, shooters accustomed to contemporary weapons will be a little confused during the first shots.

The loading of the weapon is particularly fast and easy. The cylinder being in a horizontal position, the ammunition can be introduced one by one with great simplicity… but also as already mentioned, using a speedloader! A “Moon” type clip also seems to have been used. To close the weapon, simply grab the barrel and bring it back into position. For my part I clear the lock to avoid any unnecessary friction. If the weapon is not fragile, it is still precious!

The cocking is unusual to say the least. Indeed, few shooters have ever been led to cock a revolver by pulling the barrel backward, like a semi-automatic pistol! The mechanics are flexible and perfectly adjusted, there is no parasitic gap between the mobile parts and the frame. It is with some emotion that the finger pulls the trigger! The release is clear, the trigger race is short and precise.

The sensation is incomparable, the weapon is very comfortable to shoot, almost “soft”. The recoil of the mobile parts is noticeable but does not disturb the aiming reacquisition. The shots follow one another, we quickly take this confusing habit of shooting with a semi-automatic revolver. The recoil is perfectly in line, the weapon is alive, but raises a little on the hand allowing to chain successive shots very fast. To test the reliability of operation, we had fun firing a few rounds of ammunition at a high rate. A cylinder is fired in less than four seconds! To an outside observer, the noise and rate of fire immediately evoke that of a pistol.

The weapon pleasantly surprised us with its flexibility and operation, but also with its accuracy. His reputation is perfectly justified, since we obtained a very respectable 50 points out of 60 at the distance of 25 m.

For these tests, we duplicated a .455 Webley Mk.II ammunition (with a 20mm cartridge case) from .45 Long Colt cartridge cases. The procedure is quite simple but requires minimal tools. First, the thickness of the rim must be rectified from the front. A small jewelry lathe is enough for this operation, the thickness of the rim is reduced to 0.8 mm. The case thus modified is cut to the desired length. The choice of bullets is quite vast, molds even allowing to reproduce the service bullet. We chose to use a common and available projectile, a bullet intended for the .45 ACP. Our bullets come from the “Balleurope” production, conical with a diameter of 11.48 mm and a weight of 230 grains. The reload protocol is simple and traditional. We used a classic Lee Precision branded three-element “carbide” toolset. Particularly economical, it nevertheless ensures good quality and excellent functionality. All ammunitions were loaded with the French SNPE A1 powder.

To conclude

Few handguns have brought me so many emotions: you shoot a mythical, rare weapon, and witness from a glorious gunsmithing period. Its novel and “retro-futuristic” design allowed it a film career, illustrating itself in the hands of Humphrey Bogart (The Maltese Falcon, 1941) and Sean Connery (Zardoz, 1974). Its accuracy would certainly allow it to be able to shine in competitions with antique weapons, but how many owners would agree to shoot with this weapon? This piece is particularly rare and expensive. Its classification in France in the D category (“free” access for an adult) certainly makes it available to the ” general public” but it is still necessary to find a copy and accept to pay the price of its rarity.

Its concept, although simple and effective, has certainly contributed to the evolution of semi-automatic systems… in one way or another! For amateurs or “originals” like myself, the Italian firm Mateba has produced a semi-automatic revolver partly based on the operating principles of the Webley-Fosbery. If the line is resolutely modern, these weapons will certainly attract the attention of stand neighbors.

Julien Lucot & Arnaud Lamothe

This is free access work: the only way to support us is to share this content and subscribe. In addition to a full access to our production, subscription is a wonderful way to support our approach, from enthusiasts to enthusiasts!

Sources:

“The Webley Story” par William Chipcase Dowell, Commonwealth Heritage Foundation, Kirkland, Washington: 1987.

« Cibles », Issue# 446

« La Gazette des armes », Issues# 164 and 431

Video of the YouTube channel “Le Feu aux Poudres”, by comrade Thomas:

The website and videos of Forgotten Weapons, Ian Mc Collum:

https://www.forgottenweapons.com/

The website http://webley-fosbery.com/

Acknowledgements:

Jean Michel Riomet, for organizing the test of the weapon:

http://jmpcollectarmes.canalblog.com/

Gilles Sigro for his technical assistance.

http://www.armurerietoulouse.com

Thomas from “Le Feu aux Poudres », for the picture of the 1901 model.